Trade and Travel Between Loudoun County and Maryland During the Civil War

Essential Goods Scarce in Northern Loudoun

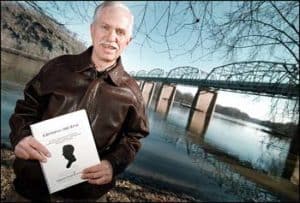

Author Taylor Chamberlin stands at the Potomac on the Virginia side near Point of Rocks, Md., the nearest place for residents to shop during the war.

The woman had $10 for food and clothing when she crossed the Potomac River into Maryland in May 1864 and bought a pair of shoes, eight yards of fabric, eight large cookies, four pounds of sugar, a quart of molasses, pint of oil and half-plug of tobacco.

Her trip was reported in the Waterford News![]() , a short-lived newspaper published by some town residents loyal to the Union.

, a short-lived newspaper published by some town residents loyal to the Union.

Although the activity sounds ordinary, such trips were often extraordinary during the Civil War because essentials such as shoes, coffee and sugar were impossible to find in northern Loudoun County. The nearest place to shop was in Point of Rocks, Md., which was under Union control.

According to a book by county residents Taylor M. Chamberlin and James D. Peshek, Crossing the Line: Civilian Trade & Travel Between Loudoun County, Virginia, and Maryland During the Civil War, residents of Waterford and Lovettsville, even those loyal to the Union, could not count on permission to shop at Point of Rocks.

The book explores a little-known part of life during the war, daily commerce for civilians living near the Potomac River, the border between Confederacy and Union. From the beginning of the war, crossing the river was difficult because the Confederates burned bridges at Harpers Ferry, Berlin (now Brunswick) and Point of Rocks.

"Although done primarily to deter a possible Yankee invasion, this action also served to inhibit contact between 'disloyal' citizens and Federal troops guarding the Maryland side of the river," according to the book. "Needless to say, it was extremely unpopular among local Unionists."

After that, residents and soldiers were dependent on a ferry to cross in either direction. Sometimes, the Federals stopped the ferry for security reasons, and other times, the Confederates did the same to disrupt trade benefiting the Union.

"It was like living in a foreign country," Chamberlin said in an interview. "It didn't quite fit the glamour of the war after it ended. This was what people didn't talk about."

The woman whose story appeared in the newspaper was not identified, but she addressed her account to "some of my readers, particularly those living in the United States, may like to know how shopping is carried out in Dixie . . . hoping it may prove a salutary lesson to them, and teach them to better appreciate their blessings."

She first had to find a horse and wagon to make the nine-mile trip, difficult because of numerous raids in the area by both armies. Eventually, she found what she needed and set off alone to the ferry.

She did not trust her husband to make the trip because she "knew he would spend all ten dollars in some foolishness and tobacco. . . . We were out of sugar, and so tired of rye coffee and sassafras tea; salt was gone, pepper quite; ginger, soda, spices, all were wanted; matches I must not forget, for we used the last this morning."

When she arrived at the ferry landing, a "motley collection" of about 50 other civilians was there, some having traveled 50 miles. After waiting quite a while, the boatman arrived, and the woman sat on a narrow board in the skiff to make the crossing.

Before she could take her purchases back to the ferry, she had to visit the government representative "to show I was no rebel."

Chamberlin said the buying trips weren't made because people were starving but rather for the things not manufactured or available at home.

"What they wouldn't have is salt and sugar and needles," he said. "Clothes would reach a point where they were not repairable. The quality of life declined."

Peshek compiled data contained in a government ledger at Point of Rocks that listed about 1,700 individuals who made more than 6,000 shopping trips to Maryland during the war. Chamberlain found the ledger while researching his family history. He could not find reference books on the subject of the civilian purchases across the lines so decided to write one.

Peshek needed two years, often working at night, to create a database that contains every entry in the ledger. All entries are listed on a CD-ROM available for research at the Waterford Foundation and Thomas Balch Library.

He also created a chart showing the total value of transactions, as recorded in the ledger, between November 1863 and May 1865. Blank areas designated Sundays and holidays and all dates when Virginians weren't allowed to cross the border.

Transactions range from less than $10 to more than $3,500. The larger amounts were spent after the war had ended and were made by retail businesses to stock their stores.

Washingt on Post article

January 2, 2003