The Sioux Created a Landscape of Pastureland in Loudoun and Fauquier Counties

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

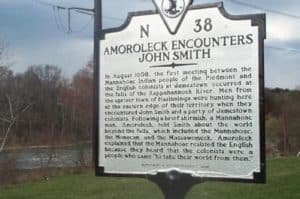

Meeting John Smith and the indian, Amoroleck.

Road marker in Fredericksburg, Virginia

In Loudoun and Fauquier counties, the indian heritage involves five major Indian nations: Sioux, Algonkian (mainly Powhatan), Iroquois, Susquehannock and Piscataway.

The Sioux were by far the most populous and occupied the largest area. In Loudoun, they lived west of the Catoctin and Bull Run mountains, and in Fauquier they roamed throughout the county.

The Sioux were first heard of in the summer of 1608, when Capt. John Smith and six "Gentlemen" and six "Souldiers" -- quoting Smith's "Generall Historie of Virginia" -- sailed up the Rappahannock River. At the falls near present-day Fredericksburg, they captured a Sioux Indian, and through Smith's Indian interpreter, Mosco, the questioning began.

The captive, "looking somewhat charefully, and did eate and speake." He said that his name was Amoroleck and that he was a "Mannahock," a 17th- and 18th-century name for the Sioux Indians.

Smith, like many adventurers who explored eastern North America, was intent on discovering a water passage to the West, so he asked Amoroleck "how many worlds he did know." Amoroleck replied that "under the skie that covered him . . . were the Powhatans, with the Monacans [related to the Sioux] and the Massawomeks [Iroquois] that were higher up in the mountaines."

Smith then asked Amoroleck "what was beyond the mountains." Amoroleck replied, "The Sunne: but of anything els he knew nothing because the woods were not burnt," referring to the Indians' practice of burning the woods to attract big game.

Amoroleck said his Mannahocks were friendly with the Monacans, who lived to the west, but were wary of the Massawomeks [Iroquois], who lived "upoun a great water [the Great Lakes], and had many boats, and so many men that they made warre with all the world."

Smith asked Amoroleck about the country east of the Blue Ridge, and on a rough map the Indian positioned the main Mannahock villages, all along the Rapidan and Rappahannock rivers. One of these villages, sometimes spelled Tauxuntania in Smith's "Generall Historie," appears on the Fauquier side of the Rappahannock, somewhere between Kelly's Ford and Waterloo.

The day after Smith's initial interview with Amoroleck, the captain's party went ashore to meet four "Kings," or tribal leaders, who were Amoroleck's compatriots. The Indians traded their bows and arrows and tobacco bags and pipes. Smith wrote that "our Pistoles they tooke for pipes, which they very much desired, but we did content them with other Commodities."

"And so," Smith said, "we left foure or five hundred of our merry Mannahocks, singing, dauncing, and making merry, and we set sayle."

History hears no more from Amoroleck and little more of his merry Mannahocks. But on John Smith's 1612 map of Virginia, there are four Sioux villages shown at the dawn of Virginia's history, along the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers.

The next specific citation of the Sioux appears in 1669, but their appearance is implied in 1655, when Virginia's General Assembly noted that "many western and inland Indians are drawne from the mountaynes, and lately sett downe neer the falls of James River at Richmond, to the number of six or seaven hundred."

Most of these Indians were Mannahocks or their Monacan allies, driven southeast by incursions of tribes -- probably Iroquois -- penetrating the Blue Ridge into the Virginia Piedmont. From their temporary quarters, near the James River falls, the Mannahocks, in about 1656, moved 25 miles up the James to present Goochland County, where their name survives in Mohawk [Mannahock] Creek. But again, the Iroquois, and now the Susquehannock, drove the tribe farther west and into the mountains.

Susquehannock raids in the 1670s also forced the Mannahock still living in Loudoun and Fauquier to move south and west. Their refuge became Kentucky's Big Sandy River, later known as the River of Totteroy, an Iroquois name for the eastern Sioux.

In 1669, when the Virginia colony counted its Indians in populated regions, 50 "Mattehatique" (Mannahock) were living between the James and Rappahannock rivers. The colony then required Mannahock bowmen to bring in an annual bounty of 10 dead wolves or their skins.

Next year, when John Lederer, a German physician, explored the western regions of future Fauquier and possibly Loudoun (his route is unclear), he encountered no Indians in the area. He did, however, observe a landscape created, in part, by the Sioux. The burnt woods related by Amoroleck to John Smith, 62 years before, were still there.

The Sioux were primarily hunters of large game: buffalo, deer and elk. To attract these grazing animals, which became their food, raiment and shelter, they burnt large sections of the forest so they would revert to grassland.

Before reaching the Blue Ridge, Lederer, in his comments regarding the expedition, spoke of "Savanae," which he said were "low grounds at the foot of the Apalataeans [Appalachians]." He said that about the beginning of June, "their verdure is wonderful pleasant to the eye, especially of such as having traveled through the shade of the vast Forest, come out of a melancholy darkness of a sudden, into a clear and open skie." Lederer mentioned that on the savanna grew "luxurious herbage," which "invited numerous herds of red deer to feed."

In 1705, Robert Beverley wrote a description of the same region in his "History and Present State of Virginia."

"The Heads of the Rivers afford a Mixture of Hills, Vallies and Plains . . . in some Places lie great Plats of low and very rich Ground, well Timber'd in others, large Spots of Meadows and Savanna's, wherein are Hundreds of Acres with out any Tree at all; but yield Reeds and Grass of incredible Height."

Forester Hu Maxwell, commenting in 1907 in the journal American Anthropologist on the practice of burning the woods, conservatively estimated that the Indians deforested 30 to 40 acres for each tribal member. "The tribes were burning everything that would burn. . . . if the discovery of America had been postponed five hundred years Virginia would have been pasture land or desert."

In many of the early and mid-18th-century deeds to lands in Loudoun and Fauquier, the phrase "poisoned field" appears. Surveyors, coming across areas of briar and scrub, thought the groundwater was the cause of the sparse growth. They didn't realize that decades before, the thickets were the savannas mentioned by Lederer and Smith.

Thomas Jefferson's 1785 book, "Notes on the State of Virginia," mentions the "Manahoac" for the last time in early writings. Without citing numbers, he noted that they once lived "between Potowmac and Rappahannoc," precisely the region of Loudoun and Fauquier.

Not until the early 1880s did the Manahoac or Mannahock names become linked to the Sioux. Ethnologist Horatio Hale made the connection in talking with remnants of the eastern Sioux tribes. Indian historians told Hale that the last full-blooded eastern Sioux, Waskiteng (Little Mosquito), had died in 1871 at 106.

For further reading: Horatio Hale, "The Tutelo Tribe and Language," in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, xxi, 114 (Philadelphia, 1883); James Mooney, "The Siouan Tribes of the East," Bulletin 22, Bureau of American Ethnology (Washington, 1894); David I. Bushnell Jr., "The Manahoac Tribes of Virginia, 1608," Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 94, 8 (1935).

Copyright © Eugene Scheel