Revolutionary War — John Champe, A Double Agent

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

"John Champe on his way to 'desertion' ". First published by Currier and Ives. This reproduction of the original Chromolithograph is courtesy of the Loudoun Museum

The saga of John Champe, the Loudoun County man who became a double agent to capture the Revolutionary War traitor Benedict Arnold, is a tale worthy of grand opera.

In late October 1780, near Bergen, N.J., the Loudoun Dragoons were encamped a few miles from the Hudson River. Champe, 28, was the cavalry unit's sergeant major; Maj. Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee was its commander. Across the river was New York City, which housed British headquarters and one very famous American renegade.

A month earlier, Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold, one of the ablest of Continental officers and a hero of the 1777 Battle of Saratoga, deserted to the British for 20,000 pounds, equivalent to about $1 million today. His desertion was prompted by several reasons, among them dissatisfaction with Gen. George Washington's leadership, being passed over for promotions and being accused (though exonerated) of appropriating money.

"Arnold had given up hope of ever being appreciated or repaid by an ungrateful nation," Willard Sterne Randall wrote in "Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor."

Washington hungered to capture Arnold, who was in New York recruiting loyalists to fight for the British. His defection had prompted several American soldiers to change sides. Washington called for Lee, his ablest cavalry officer, and told him that he wanted Arnold brought back -- alive. He added in an Oct. 20 letter to Lee, "My aim is to make a public example of him."

The general's plan called for a soldier who could ride stealthily through the many American pickets and board a boat that would cross the Hudson. In New York, the American would present himself as a deserter and gain Arnold's confidence. With the aid of an accomplice, the American would kidnap Arnold and hustle him aboard a waiting boat. Arnold's resistance should be minimal: He was nearing 40 and had a crippled left leg from a Hessian bullet at Saratoga.

Lee told Washington that the man for the job was John Champe, a native of "London County in Virginia" whom Lee had enlisted in 1776. In his "Memoirs of the War of the Southern Department," Lee described Champe as "rather above the common size -- full of bone and muscle . . . grave, thoughtful, taciturn -- of tried courage and inflexible perseverance."

From Stone Walls, a Tribute to Bravery

In 1907, Col. Floyd Harris, a wealthy sportsman, purchased Stoke, a manor house a mile south of the dilapidated stone walls that once made up John Champe's cottage.

Nearly every day Harris drove through Little River at Champe's Ford, in view of the ruins. Unaware of Champe's fame, Harris dismantled the cottage walls about 1920 and at his expense had the stone bridge built across the ford.

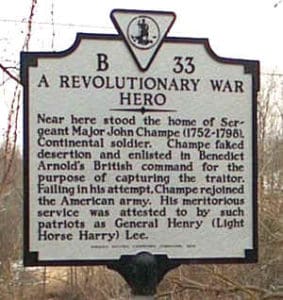

In 1927, the Virginia State Commission of Conservation and Development began its erection of historical markers. Wilbur C. Hall, Loudoun County's delegate to the General Assembly and a history lover, prompted the state to honor Champe with Marker 33-B.

In early summer 1934, the marker was placed by U.S. Highway 15 (now U.S. 50) at a lay-by close to the few stones that remained from Champe's home.

Intrigued by the marker and subsequent newspaper accounts about the cavalryman, Harris decided to have an obelisk built from remaining stones at the Champe homestead. The memorial was unveiled on Oct. 22, 1939, and still stands.

Champe accepted the assignment. He was undeterred by the dangers and difficulties of the mission but was bothered, according to Lee, "by the ignominy of desertion, to be followed by the hypocrisy of enlisting with the enemy." Not one Loudoun Dragoon had ever deserted to the enemy.

About 11 p.m. on Oct. 20, 1780, Champe rode off with his arms, saddlebags, orderly book and five guineas (about $20 today), supplied by Lee. Five miles away, a boat awaited him on the Hudson River. Shortly after Champe left camp, an American patrol spotted him, and, when he did not halt, gave chase. An aide informed Lee of the escape, but the commander, to buy time, appeared not overly interested. The aide left but returned shortly to inform Lee that the escapee was his sergeant major, Champe. Hoping he had given Champe time to escape, Lee finally ordered a patrol to go after him. Only minutes ahead of the pursuing patrol, Champe dismounted, ran through the marsh and plunged into the Hudson to board the boat to New York City.

There, Champe was captured by British pickets and questioned by a host of ever-higher-ranking Britishers, eventually coming before their commander, Sir Henry Clinton. To these interrogators, Champe repeated that Americans such as he, following Arnold's example, had already deserted or were about to.

Clinton then gave Champe a few guineas and introduced him to Arnold, who was impressed with Champe's countenance and demeanor. Arnold made Champe one of his recruiting sergeants in the American Legion. With that position, Champe had uninterrupted access to Arnold's home near the southern tip of Manhattan, overlooking the Hudson River.

All the while, Champe, via a conspirator, was communicating with Lee. Ten days after his defection, Champe sent Lee his plan to abduct Arnold. The traitor's fenced garden overlooked the river, and each evening before retiring, Arnold strolled through the garden. Bordering the garden was a lane. Champe would pry fence boards loose, and he and his conspirator would hustle a bound-and-gagged Arnold through the fence and the back alleys of lower Manhattan to a waiting boat.

If anyone questioned Champe and his accomplice, Champe would say they were taking a drunken soldier to the guard house.

The plan failed. The day before the planned capture, Arnold moved his quarters to another part of Manhattan, taking Champe, his recruiter, with him.

Arnold's American Legion, made up largely of deserters, then sailed to join other British armies in Petersburg, Va.

In his native state, Champe fought with Arnold's troops, sometimes against Lee. After some weeks, Champe deserted, making his way to the Appalachian Mountains before rejoining Lee's command.

In his "Memoirs," Lee wrote that Champe's "whole story soon became known to the corps . . . heightened by universal admiration of his daring and arduous attempt." Washington then excused Champe from further war service, and he retired to family life and seven children in Loudoun County.

Champe became doorkeeper and sergeant-at-arms for meetings of the Continental Congress in Philadelphia and Trenton in 1783.

Late in his life, he performed an act of kindness that ensured that his heroics would outlive him. A British traveler, Capt. Cameron, knocked on the door of Champe's cottage near Aldie, seeking refuge from a thunderstorm. Welcomed inside, the visitor reminisced with his host about their war careers as the night passed. Champe told his guest how he tried to capture Arnold. Cameron wrote the story in his diary and eventually sold the tale to Blackwood's Magazine, a British publication.

During the Civil War era, Champe's exploits were memorialized in the name of a Confederate infantry company -- Champe's Rifles was organized in Aldie in May 1861 -- and by a republishing of Lee's "Memoirs" in 1869 by his son, Robert E. Lee, the Confederate commander. Robert Lee was a toddler when his father, while imprisoned for indebtedness, was writing "Memoirs."

Champe himself never saw his story in print. He died at age 46 in 1798

Copyright © Eugene Scheel