Purcellville's Orchard Grass Seed Mill

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

Purcellville history »

Sufferers of "orchard grass fever," caused by the blooming of that grass in late May, might recall that the allergy was far more prevalent in Virginia during the 1940s and '50s. The town of Purcellville, population in the 900s, was then considered by Virginia farmers to be the orchard grass capital of the United States. About orchard grass »

Orchard grass was an important munitions packing material in World War II

During World War II and the Korean War, ammunition, artillery shells and small arms and rifles were packed in orchard grass seed, and the big Virginia processor of those seeds was Contee Adams Seed Co. of Purcellville. Area farmers dubbed Contee Lynn Adams Sr., the firm's owner, "Mr. Orchard Grass."

Before World War II, Europe was self-sufficient in orchard grass production, with Denmark being the major supplier of this important plant used for animal feed, packing material, and ground cover. It only took a few years after the invasion of Denmark for the United States to step into Denmark's role. Most of the orchard grass seed produced during the war came from 17 counties in Virginia–with Loudoun being the top producer.

With World War II in full swing in the Atlantic and Pacific theaters, munitions experts were looking for a stable packing to transport ammunition and small arms. The dense orchard grass seed was safer than wood chips, which had a tendency to shift, sometimes causing the shells or arms to rub against the packing crate. Once the ordnance were unpacked, the seed could be given to farmers in Britain and freed territories so they could plant it to feed stock.

"Everybody" -- meaning Virginia farmers -- "got into it then," Johnson told me. The state's production of orchard grass rose from 1.7 million pounds in 1940 to 2.7 million pounds in 1943. Loudoun produced 400,000 pounds of that total in 1943.

Catoctin Farmers' Club minutes record that orchard grass "in the dirt" sold for $1 to $2.50 a bushel (14 pounds) in the early 1940s. Refined orchard grass seed jumped from $3.50 a bushel in 1940 to $4.80 a bushel in 1943.

History of Purcellville's Orchard Grass Seed Mill

The major buildings of the complex that processed the grass from about 1875 until 1991 still stand in downtown Purcellville. They are by the old railroad depot that marks the end of the W&OD bicycle trail, once the Washington & Ohio Railroad, later the Washington & Old Dominion Railroad.

Before the rails came, "Purcellsville," to quote New York Times correspondent "J" in 1862, "cannot be dignified with the title of village, consisting of a few straggling houses on the Winchester and Leesburgh [Turnpike]," today's Main Street.

But a week after the Washington & Ohio Railroad reached town on March 31, 1874, the Leesburg newspaper The Mirror waxed: "The running of the trains . . . has set the little village aglow with activity. The scene around the depot on Saturday reminded us of accounts we have read of cities and towns springing up as it were, in a night."

In May 1874, The Mirror wrote about several new buildings by the tracks, including a steam-powered sawmill owned by John T. Hirst and John R. Smith. The two men soon diversified the operation, purchasing a machine to separate seed from chaff. Orchard grass was among the refined grains and grasses but was not a major crop. Wild onions often grew among the orchard grass, and the onion bulbs were about the same size as the orchard grass seed, and thus were hard to separate.

In 1875, the firm of Milton, Bolyn & Co., run by John and Theodore Milton and Edward Bolyn, began selling orchard grass and other seeds, fertilizers and agricultural implements in the four-story frame building that had been built the previous year for John James Dillon, an entrepreneur. The structure, which now houses offices, still bears his name and the date 1874.

As with many frame mills, susceptible to spontaneous combustion of grain, errant sparks and lit cigarettes, the Smith & Hirst mill burned in 1882, was rebuilt the next year, burned again in 1904 and was once more rebuilt in 1905. The mill now is the recently opened restaurant, Magnolias at the Mill.

During the second fire, one of the station hangers-on was sleeping it off under a freight car parked on the siding. Awakened by the blaze, he exclaimed "Dead in Hell, just as I expected." Hirst later heard his story and passed it on to his son J. Terry Hirst, who told me.

In 1921, the mill, operated by electricity since 1912, was sold to William Henry Adams, formerly of Rectortown, and he and son Contee Lynn Adams, always known by his first name, changed the mill's name to Loudoun Valley Milling. Purcellville was near the center of the valley, framed by the Catoctin Mountains on the east and Blue Ridge on the west.

By the late 1930s, with the growing prominence of hybrid corn and orchard grass, a feed of choice for the area's burgeoning dairy and horse industries, the Adamses began to concentrate their business on the cleaning of seed. Nearby mills at Irene (the railroad stop for Hamilton) and Round Hill, both run by the Wilkins & Rogers firm, took up the slack in grinding grains.

Most of the orchard grass used for seed was cut in May or early June. Farmers called the grass's blooming "coming into head" or "coming to a head." There was a second cutting, before the grass went to seed, in late May or early June.

But all seasons were busy, for orchard grass seed could keep year round with only a slight loss in germination.

Contee Adams loved people and history. One of his favorite reminiscences was when, as a teenager, he picked up John Singleton Mosby at the Marshall railroad station and drove the aged Confederate veteran to the Cobbler Mountains, a few miles southwest of Marshall. Mosby was trying to remember where he had hidden a mountain howitzer that he had taken from the Federals in 1864. They couldn't find the howitzer, and neither could I and a search party in the late 1980s.

Recently, I spoke with Elizabeth Reed Johnson, who lives in the house where she was born, a short walk from the mill. After graduating from Lincoln High School in 1936, she became secretary of the Purcellville elementary school. Dissatisfied with her $18 a month salary, she, after some persistence, joined Loudoun Valley Milling in October 1941 as Adams's office help at $25 a month.

Soon Johnson was managing the payroll as well as the office, and was dealing with customers. Within a few months her salary increased to the Virginia Piedmont standard of $40 a month. She remained with the firm until it closed in 1991.

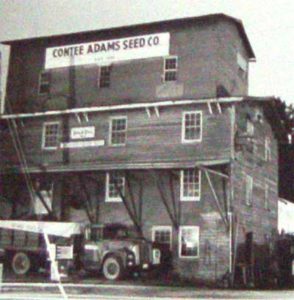

In 1943, Adams decided to concentrate solely on the cleaning of seed. He sold Loudoun Valley Milling to Wilkins & Rogers and moved his business across Depot Street, as 21st Street was then called, to the Dillon building. Adams changed the firm name to Contee Adams Seed Co.

The two businesses agreed that Adams would not grind grains or sell feed. And Howard and Sam Rogers, partners of Wilkins & Rogers, would not refine or sell seed. Both firms were on friendly, even family terms. Johnson's sister, Julia Reed Arnett, was office manager at Loudoun Valley Mill, and the six or seven employees at Contee Adams often assisted in the mill's operation when they were short-handed.

"They worked around the clock when I was there," George Edgar Conard, a retired seed cleaner from Round Hill, told me a few weeks ago. At 94, his memory was undimmed as he related the cleaning process during the early 1940s.

"Threshed seed from the farm was taken from bins and put into a hopper. Then it was fed onto screens. Some screens were course, some were fine. We gauged the [threshed] grass to see what screen we'd use to get rid of husks and [inert] matter. We also used regulated fans to separate the seed from the chaff."

The seed was heavier than the husks and dirt.

"We had three or four machines going at one time," Johnson told me. "They were made by A.T. Ferrell of Saginaw, Mich. One machine usually was for cleansing oats and barley."

Johnson then described the painstaking process of further cleansing a two-gram random sample of the cleaned mixture. After weighing two samples, Johnson would manually pick out the remaining inert matter, often onion seeds, from one sample. That sample, now nearly pure orchard grass seed, had to be from 85 percent to 90 percent of the weight of the control sample. The U.S. government required a mix that was 85 percent pure seed.

Johnson remembered that in 1943 the orchard grass seed was poured into thick paper bags displaying the Contee Adams Seed name in green, with a yellow diamond representing the seed. But soon paper was in short supply, and the seed was packed in plain burlap bags in weights of 50 and 100 pounds.

Contee Adams Seed did not directly sell the refined orchard grass seed to the U. S. government. The biggest buyers, Johnson told me, were Scarlett Seed of Baltimore and Scott Seed of New Albany, Ind., and Roanoke. Wetsel Seed of Harrisonburg, Va., and Carpenter's Seed of Mitchell's in Culpeper County also bought large amounts. Johnson estimated that not more than a quarter of the seed buyers were local farmers.

When I asked Johnson if she recalled any highlight in the seed company's operation, she remembered the visit of a Japanese delegation in 1958. The members wanted to learn the seed-cleaning business, and U. S. agricultural officials said they should visit Contee Adams.

After Contee's death in 1960, his son, also Contee Lynn Adams, but always called Lynn, took over the business, which had expanded to raising and selling Christmas trees during the somewhat-slack winter season.

I knew Lynn well, and his love of people and history was as strong as that of his father. He often told me that after he was gone, there'd be nobody left to remember the names of the farmers of the Virginia Piedmont. A hundred miles from Purcellville, I'd encounter people who would ask me, "How's Lynn doing?" People then assumed that if you were from Loudoun, you knew Lynn Adams.

In the decade before Lynn died in 1991 -- the year the seed company stopped cleansing orchard grass seed -- his church, St. Peter's Episcopal in Purcellville, was raising money to build a tower to house a bell named Loudoun.

The bell was cast in 1922 to honor Loudouners who had died in World War I.

Lynn evidently took it upon himself to raise some from customers.

I was speaking one day with Harvey "Bud" Carpenter Jr., of Carpenter's Seed at Mitchell's, and he asked me how the belfry was coming along. He never mentioned the words "St. Peter's." He assumed I knew what belfry he was talking about.

"Slowly," I answered.

"Well, I sent Lynn a donation," Carpenter said. "Keep me informed."

Often, when Lynn told stories about Loudoun old-timers, people would ask if he were a Loudoun County native. After saying that he was born and grew up in Purcellville, Lynn would answer, "No."

"But you were born in Loudoun," they'd counter. And Lynn would reply, "I know, but my father wasn't."

Copyright 2004 © Eugene Scheel

The Mill is Now home to Magnolias at the Mill Restaurant

The restoration of the mill into its present state of "Magnolias at the Mill" began in 2001 and was completed in 2004 by the late Bruce Brownell who worked tirelessly to preserve the look and feel of the building while simultaneously creating an ambience that is at once both modern and historic.

About Orchardgrass

Orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata L.) is a perennial, cool-season, tall-growing, bunch-type grass with an open sod. It starts growth early in spring, develops rapidly and flowers during May under Pennsylvania conditions. Orchardgrass is more tolerant of shade, drought, and heat than timothy, perennial ryegrass or Kentucky bluegrass but also grows well in full sunlight. Orchardgrass is adapted to the better well- drained soils and is especially well adapted for mixtures with legumes such as alfalfa or red clover. It will generally persist longer than the other cool-season grasses in frequently cut, properly managed alfalfa mixtures.

Orchardgrass is a versatile grass and can be used for pasture, hay, green chop, or silage. A high-quality grass, it will provide excellent feed for most classes of livestock.