Old Place Names Reveal Leesburg History, Lore

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

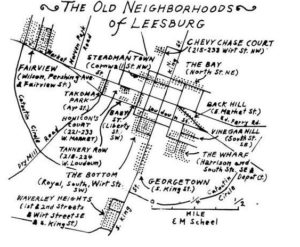

Leesburg, 200 years old this year, abounds in neighborhood and street nicknames that once were part of common speech but are rapidly waning.

In the early 1970s, I walked around town with five men whose keen ear and memories provide the foundation for this column.

Here are the names — most of them unofficial — that they told me about, with the names and places listed by quadrant.

Northwest

Steadman Town was the name for the 19th-century homes along Cornwall Street. In the early 1800s, many of the lots were owned and then sold by Col. James Steadman, an officer in the Loudoun Militia. In the 1890s, this section acquired the name Coopertown, as some of the town’s barrelmakers had shops in the area.

Parlaying on the appeal of Washington’s exclusive suburb, developer Thomas D. Paul gave the name Chevy Chase Court to the residences at 215 through 233 Wirt St. The four brick duplexes and two single-family homes form the Virginia Piedmont’s earliest garden-apartment complex. They were built in 1940.

Cornwall Street

Fairview, Loudoun County’s oldest 20th-century subdivision, dates from 1922, as an observant reader of street signs — Pershing Avenue, Wilson Avenue — can attest. The lots had a 25-foot frontage, which encouraged buyers to purchase three or four. Homes built upon the lots were quite affordable; many cost less than $1,000.

Northeast

The Bay is the oldest African American section of town, with its North Street development dating mainly from after the Civil War. The name is a shortening of Murderer’s Bay, a nickname given by whites to that section of town because, as my informant told me, “there were many slicings and cuttings.”

Back Hill is along Market Street, between Church and Harrison streets, in back of the courthouse complex. The hill was once a favorite spot for sledding. Even after the street was paved in the early 1920s, the hill was impassable for traffic in wintry weather. In an earlier era, heavy wagons and stagecoaches approaching town from the east took Loudoun Street, whose rise is far gentler than that of Back Hill.

Southwest

Takoma Park was a largely African American area of small houses on both sides of Ayr Street between Loudoun and Market streets. The east side of Ayr was once in town, and the west side was in the county. Thus the nickname Takoma Park, the Maryland city that was long split between two counties and shares a border with Washington, D.C.

Honicon’s Court got its name from Leesburg’s famed post-World War II contractor, Claude Honicon. He specialized in well-designed stone bungalows. Seven of them, built in 1952-53 at 221 through 233 West Market Street, grace Loux doun’s first cul-de-sac.

Tannery Row consists of four frame houses at 218 through 224 Loudoun Street that date from the early 1870s. They were built for the workers of the nearby Norris Brothers’ planing mill and lumber works. The Norris firm built many fine Leesburg buildings, including the courthouse and St. James’ Episcopal Church. But part of William Kitzmiller’s tannery was here before Norris Brothers arrived, and that explains the name.

Baby Street is the block of Liberty Street between Loudoun and Market. Prior to the 1950s, it had the only town playground that the street’s black families could use.

The Bottom describes the low-lying area south of Loudoun Street near Town Branch, which flooded during high water. Both blacks and whites often called it Black Bottom because many African Americans lived along King, Royal and Wirt streets in that area. One African American woman recently told me, “We now call it Spanish Bottom.”

Georgetown runs along both the east and west sides of King Street; the west side, with its view of Catoctin Mountain, was built first. The 1880s and ’90s neighborhood takes its name from Leesburg’s first name, honoring King George II. It was a trendy section of town in the early 1900s. The Southern Railway’s new station was built here in 1900, and watching the trains and their passengers was a pleasant pastime.

Waverley Heights, a neighborhood of 1920s vintage along First, Second and Wirt streets, takes its name from the circa 1895 home named Waverley at the southeast corner of King Street and First Street SE. The house, now offices, is attached to a myriad of newer office units called Waverly Park — a name the well-educated Baltimore steel magnate Robert Hempstone, builder of Waverley, would have faulted for leaving off the last “e.” Hempstone’s intention was to honor Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley Novels, popular reading in the Victorian age.

Southeast

In about 1890, two barrels of cider on a wagon driven by Joe Waters and a Mr. Myers fell off and broke on a ride up the South Street rise from Harrison Street. The smell, driven by prevailing westerly winds, lasted for weeks, bestowing the name Vinegar Hill upon the rows of houses along South Street.

The Wharf was the name for the pre-1985 Market Station area around Harrison and South streets and Depot Court. It was Leesburg’s main commercial and industrial hub, dating from 1860 when the railroad, then the Alexandria, Loudoun & Hampshire, reached town. A mill, stockyards, an ice plant, a limestone quarry and woodworking shops of every description filled this area where the first passenger and freight stations stood. It was the unloading of goods from the trains that gave The Wharf its name, not unique to Leesburg.

Describing the first train to enter town, on May 17, 1860, the Leesburg newspaper, the Washingtonian, editorialized: “We are now hitched to the rest of the world, about an hour and a half to two hours’ travel from Alexandria and Washington.”

So what else is new?

The five native Loudouners who shared these names in the early 1970s were Thomas B. Hutchison, then recently retired as Loudoun County commissioner of the revenue; Emmet Jackson, a dean of the African American community who worked for several downtown Leesburg businesses; Emory Plaster, a descendant of the Norris brothers and a retired town official; Frank Raflo, clothier, writer, county supervisor and newspaper editor (his 1975 “Leesburg Lore” booklet covered some of the same ground as this column); and Melvin Lee Steadman Jr., a retired clergyman and historian whose 1968 “Walking Tour, Leesburg, Virginia” was the first guide to the old town.x

Copyright © Eugene Scheel