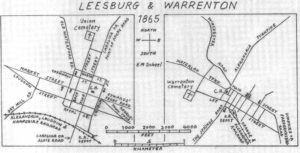

The Reconstruction Years: Tales of Leesburg and Warrenton, Virginia

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

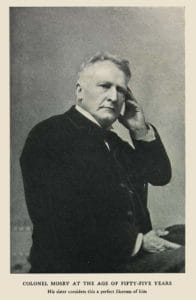

The Memoirs of Colonel John S. Mosby![]()

Mosby Heritage Area Association![]()

After so many turbulent years during the Civil War, life in Leesburg and Warrenton slowly returned to a modicum of normalcy as 1865 rolled into 1866.

The way was easier in Loudoun County, where non-slaveholding Quakers and Germans in the west led community acceptance of civil rights for freed slaves and compliance with -- but not approval of -- the federal occupation force. Fauquier County, however, was less agreeable to the new order. In Warrenton that winter, wood -- the only available fuel and the primary building material -- sold for $5 a cord. Most people earned about a dollar a day.

The spirit of reconciliation was fanned by articles and editorials in the counties' major newspapers, the Democratic Mirror in Leesburg and the True Index in Warrenton. In the initial postwar issue of the Democratic Mirror on May 31, editor Benjamin Sheetz wrote of "a very pretty flag emblazoned with the stars and stripes throwed to the breeze" atop the Loudoun County courthouse.

Slavery — "the fruitful source of all our trouble — is extinct," Sheetz exulted.

Editors Lycurgus Caldwell and John Finks had their first postwar issue of Warrenton's True Index off the presses Nov. 11. In it they stated that ". . . universal freedom and a restored Union are facts which must be recognized and accepted."

But former slaves becoming a productive part of free society required more than soaring spirits and optimistic words. It would take education.

Isolated records indicate that at war's end fewer than half the African American population in Fauquier could read. Fewer still could write.

A month before the war ended, a prescient U.S. Congress established the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands. Commonly called the Freedmen's Bureau, it had two Loudoun headquarters, in Leesburg and Middleburg. Its Fauquier headquarters was in Warrenton.

A bureau circular produced in May 1865, posted in public places and published in the Leesburg and Warrenton newspapers, pointed out to the black populace the erroneous belief, held by some, that ex-slaves were entitled to their former masters' property and that the former masters had to support them, regardless of whether they worked.

The circular stated that to maintain "a state [society] of freedmen," blacks had to be self-supporting and had to recognize the fidelity of a contract. The circular mentioned average wages paid to freedmen who farmed for others: $12 to $15 a month with board, clothes and medical attention; $20 to $23 a month without board. Female cooks and house servants received about half those amounts. People who could not support themselves or their families were to be issued "destitute rations."

To help those who were down and out, in February 1866 African Americans in Leesburg and the vicinity established the "Colored Man's Aid Society." Editor Sheetz commented approvingly, noting a year later that without such a group many former slaves would "go supperless to miserable beds."

In Warrenton, after editors at the True Index warned that the vast majority of blacks "domiciled here prefer to lead the life of vagrants," a group of African Americans organized in early autumn 1865 to address the issue and campaigned for a school in their community.

S. Fannie Wood, a white woman from Middleboro, Mass., taught at this first school, which was opened in February 1866 in a rented building at Fourth and Lee streets. She named it the Whittier School, in honor of the Massachusetts Quaker poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier. The New England Freedmen's Aid Society of Boston paid her salary and room and board.

This was a common arrangement of the time: northern organizations, frequently spearheaded by Quakers, funding Freedmen's Bureau schools in the South. The teachers were called missionaries by the Times, an influential Richmond newspaper, and described as "pretty Yankee girls with the smallest of hands and feet."

The teacher at Leesburg's first Freedmen's school, established sometime in 1866, was Caroline Thomas, a white woman. The Philadelphia Society of Friends paid her salary and board.

A second school at the home of freeborn William O. Robey, an African American blacksmith, preacher and teacher, opened at his home the same year. A year later, Robey led a campaign to build the initial Mt. Zion United Methodist Church on North Street.

Leesburg took its schools for freedmen in stride. In Warrenton, though, there was trouble. Shortly after Fannie Wood's school opened, she received an anonymous letter from "Negroeville, Va." The True Index printed the first paragraph: "We the young men of this town think you are a disgrace to decent society and therefore wish you to leave this town before the first of March and if you don't there will be violence used to make you comply to this request."

The newspaper then reported that Wood had been "serenaded" by "songs and expressions not intended for ears polite" and warned that such an "unpopular performance" could bring back federal troops. It did, for two weeks, but after the cavalry left in mid-March, stones pelted her schoolroom.

Mayor Charles Bragg apologized for the incidents, and Lt. William Augustus McNulty, a native of Portland, Maine, and the head of the Freedmen's Bureau in Warrenton, offered to protect Wood. She thanked the mayor in a letter, noting that "my mission is of a character that might be somewhat at variance with your views." If there were further crises, the True Index did not report them.

Wood's school report for that first year noted that she taught 55 students. At night there was a second school for young adults, and John W. Pratt taught 110; 50 could read and spell. Reading and spelling were the main subjects. Later that year, other female teachers, including McNulty's wife, Abbie, taught day school in a second room.

McNulty took over night school for Pratt, and old-timers in Warrenton told me years ago that his students were amazed that a white soldier in uniform, with only one arm, would go to the trouble of teaching them. McNulty, a cannoneer, had lost his right arm in the Union siege of Fredericksburg.

Occasionally, when altercations arose, federal troops would occupy Leesburg. Sheetz wondered why, asking whether that would be the case after a crime were committed in a northern town. He thought it amusing that several times the soldiers rode into town to wage what he termed "the war against Confederate buttons and old clothes."

The wearing of the gray Confederate uniform was illegal, but Sheetz explained that the steely overcoats and slouched hats were the usual dress for many because they "had to wear the 'rebel' gray or go naked."

"A most dangerous and gallant exploit," Sheetz said in a May 1866 snippet, "was

performed in Leesburg the other day by some Federal soldiers . . . who pursued and shot at Colonel Mosby because he refuse[d] to surrender an old gray great-coat with 'rebel' buttons upon it." Col. John Singleton Mosby, the famed partisan leader during the war, practiced law in Fauquier, Loudoun and Prince William counties after the conflict.

Sometimes, Mosby would ask for a Union escort for his trips to Loudoun from his Warrenton office. He was a slight man, and he "thought some burly Quaker was going to pick a fight with him," to quote Wallace Phillips, who, as a young man, knew Mosby.

By far, the dominant local articles in the town newspapers proclaimed optimism. Writing of the first August court-time fest in four years, Sheetz stated: "Notwithstanding previous evil anticipations, we do not remember ever to have witnessed a similar occasion when better order prevailed. . . .

"John Barleycorn was totally snubbed," he wrote, using the slang term for alcoholic drink.

Three months later, Sheetz was no less cheerful: "Leesburg begins to wear the appearance of former times. The hum of business and the joyous laugh of revelry and mirth gladdens the ear as in days of yore."

A Warrenton True Index morsel told of reorganizing the library. The prewar borrowers' cards were in a desk, but it could not be found. Would persons who had taken out books please return them? There would be no fines.

A July 1865 True Index article called a Springs Road gala "the grand tourney, so long contemplated by our chivalry." It was followed by a coronation ball in Warrenton, lasting, the newspaper said, until the "shrill-toned trumpeter of the morn."

For comprehensive coverage of the reconstruction years in Loudoun County, see Charles P. Poland Jr.'s A Disharmonius Reunion, 1865-1877 in his book From Frontier to Suburbia (Marceline, Mo.: Walsworth Publishing, 1976). Selections from the Democratic Mirror are printed in Jerry Michael's The Year After (privately printed, 2000). For that era in Fauquier County, see Eugene Scheel's "The Rebuilding" in the book The Civil War in Fauquier (third printing, The Fauquier Bank, 2000).

Copyright © Eugene Scheel