With Leesburg in Their Sights, Union Troops Caught by Surprise at Ball's Bluff

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

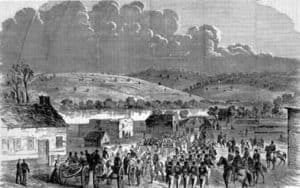

General Gorman's brigade arriving at Edwards' Ferry for General Stone's "slight demonstration," 20 October 1861 (Library of Congress)

The Battle of Ball's Bluff, initiated by a telegram from Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, commander of U.S. armies in the Washington area, to Maj. Gen. George P. Stone, commander of troops along the Potomac River in Maryland.

McClellan told Stone to "keep a good lookout upon Leesburg, to see if this movement [several Union reconnaissances] has the effect to drive them [Confederate forces] away. Perhaps a slight demonstration on your part would have the effect to move them."

This essay does not focus on the carnage that followed -- more than 300 Union dead and about 800 missing, wounded or captured from a total force of 1,780, many of them untrained and in their first action. Instead, it deals with why the debacle took place and local reactions to the second resounding Union defeat near Washington, three months to the day after the Battle of Manassas.

Leesburg was the Union destination because it was a transportation hub. There, two of Northern Virginia's main roads crossed, today's Routes 7 and 15. The town also was the western terminus of the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad line, now the Washington & Old Dominion Trail.

Of further import, if Leesburg was captured, the Confederate perimeters southeast of town -- around Manassas Junction and Centreville, about 20 miles from Washington -- would likely be abandoned for fear of a Union flanking movement from the northwest.

Leesburg also had propaganda value, besides having the Lee family name indelibly linked to it. The town was the home of John Janney, and northern newspaper reporters were eager to interview him. Janney had been elected president of the 1861 Virginia Convention, which in April voted 88 to 55 to secede from the Union. Although Janney then handed Robert E. Lee his sword and commission to lead the commonwealth's armies, he had voted against secession.

In 1861, there was only one detailed map of the Leesburg area, which had been drawn in 1852 by Loudoun County's Yardley Taylor. It showed a road leading from the Potomac River to Leesburg, 2 1/2 miles away, but it showed no bluff by the river. In reality, there was a very steep bluff, 80 to 100 feet high, and the beach by the swift-flowing river channel was a narrow one.

Two companies of Minnesota troops had scaled the bluff the night of Oct. 20, but if they did note its precipitous slope, their climb was secondary to the Confederate cannon they thought they saw -- in reality "cut cedars, their centers painted black," according to Helmi Carr, widow of the great-grandson of Minnesota scout Pelig Carr. They were lying atop a large Confederate fortification named Fort Evans for the Confederate commander, Nathan "Shanks" Evans.

"Inside the fort they had many torches burning," Helmi Carr said, "so they [the Minnesotans] would think the fort full of troops. But there were only a few soldiers inside."

Her late husband, Lester Carr, had visited Fort Evans in the late 1940s because his great-grandfather Pelig Carr was one of the Minnesota scouts, and Lester had heard the story of his maneuvers told many times.

In the 1950s, intrigued by the coincidence that Fort Evans was for sale, the Carrs bought the vast earthen star fort, which still stands in almost pristine condition, and they built a home right next to it. They became one of Loudoun's outstanding couples: Helmi a lawyer, banker and newspaper publisher, and Lester an inventor, most notably of the moon relay system, which used the moon as a passive satellite for relaying radio signals.

Pelig Carr and his fellow scouts mentioned the fort to Stone, but as the redoubt was 1 1/2 miles from the Federals' projected landing place, Stone did not worry about its presence.

During the battle, Fort Evans served as the headquarters of Gen. Evans, who did not once venture upon the field of fighting. Fellow officer Col. Eppa Hunton, of Fauquier County, noted "he was drinking freely during the day."

Liquor was the bane of many an officer. An unknown diarist and veteran of Ball's Bluff said one Confederate officer was so drunk that he rode up to a Union detachment and ordered them to attack his fellow Southerners. The Yankees, "thinking [he] was one of their own officers, obeyed, and in the resulting attack quite a number [of Confederates] were killed."

The one dead Confederate memorialized at the battlefield site is Sgt. T. Clinton Hatcher, of Hamilton. His marker reads: "Fell Bravely Defending His Native State." But there is another story, told among Loudoun Quakers. As related by Lincoln's Asa Moore Janney: "After the Unioners had thrown down their arms up on the level at the top of the bluff, he [Hatcher] yelled, 'Come on, men, let's give 'em another round!' The Northerners snatched up their guns again and all fixed straight at him. Killed him, too."

Janney added: "This is the Union version; the other is that he was killed by sharpshooters."

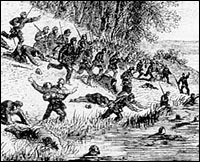

The most unusual Confederate soldier on the field was Lt. Harry T. Buford, alias Loreta Velasquez, who fitted herself with a wire frame to appear masculine and glued on a false mustache. But when she saw the retreating Union soldiers being shot as they tried to swim the Potomac, she wrote of the scene in her diary: "All of the woman in me revolted at the fiendish delight which some of our soldiers displayed at the sight of the terrible agony endured by those who had, but a short time before, been contesting the field with them so valiantly. . . . My heart stood still in my bosom."

Numerous Union soldiers were massacred retreating down the bluff and while trying to swim in battle garb. Others drowned, and for the next few weeks, bodies were fished from the Potomac, some as far downriver as Fort Washington, 50 miles distant.

Of Union survivors, Leesburg teenager Virginia Miller wrote in her diary: "We saw several wounded . . . frightfully . . . with the blood streaming from his face, from a terrible wound in the head, some with arms and legs wounded and another with his jaw bone crushed.

"Oh, it was terrible and we were in a state of great suspense and excitement, but had no idea of what a battle was being fought so near us. . . . The musketry was perfectly terrific and we could plainly see the smoke and the dead and wounded of our men and the enemy rapidly increased. It was very mournful to see the ambulances with the yellow flags, coming and going all the time."

The hundreds of enlisted Union prisoners were herded onto the courthouse green at Leesburg, surrounded by townspeople "made frantic by the victory," as the late Byron Farwell, the noted military historian from Hillsboro, told me. In his book on the battle, Farwell quoted onlookers as saying: "We've got 'em this time! Oh you infernal Yankees! Make way, Jim, I want to see a yank."

Union reaction was somber. Col. Edward D. Baker, a leader of the Union assault and Oregon's first U.S. senator, was killed late in the battle. President Lincoln, who had known Baker since 1835 and had named his second son, Edward, in Baker's honor, had picnicked with Baker on Oct. 20, the day before the battle. Now, on Oct. 22, the president was in mourning and received no White House visitors.

McClellan became the scapegoat, but he blamed his superior, aging Gen. Winfield Scott, a hero of the U.S.-Mexican War. Suspicions then fell on Stone, who was imprisoned for 189 days without charges presented against him. After his release, he never again held a responsible position in the U.S. military.

At the battlefield next March, when Federal armies occupied Leesburg, a Michigan detachment rode to Ball's Bluff, the New York Times noted, "and buried the whitened bones of the brave Union soldiers who fell on that field on October last."

Union Col. James More's words were more graphic. He wrote, "No kindly feeling seems to have actuated those living in the vicinity to care for the dead, and after they were permitted to lie for days, exposed to the ravages of animals, were only coffered with earth when the air became foetid with the odor from the bodies."

More's men gathered up more remains in December 1865 and buried them on the bluff in 25 graves forming a circle -- the typical way of interring unknown soldiers in the South. That month, the circle became today's Ball's Bluff National Cemetery.

In 1866, writer Herman Melville published a set of poems titled "Battle -- Pieces and Aspects of the Civil War." One poem dealt with Ball's Bluff, and its final verse reads:

Weeks passed; and at my window, leaving bed,

By night I mused, of easeful sleep bereft

On those brave boys (Ah War!, thy theft);

Some marching feet

Found pause at last by cliffs Potomac cleft;

Wakeful I mused, while in the street

Far footfalls died away till none were left.

Horatio Trundle, who lived near Ball's Bluff at Exeter, campaigned for the battlefield's preservation in the late 1930s, but nothing came of his pleas. Only in October 1981 did a second effort begin, after a developer bought the site's surrounding 475 acres. For days, Hugh Harmon, then Loudoun's tourism director, paraded around Leesburg and up to Ball's Bluff in a Union uniform. The attention he got from the media aroused politicians, and, thus, the Northern Virginia Park Authority bought 78 acres of the battlefield in 1984. Subsequent purchases by the authority and Town of Leesburg have increased the park's size to more than 200 acres.

For more information, see Death at Ball's Bluff in "Loudoun County and The Civil War, 1961" by John Divine; "Ball's Bluff: A Small Battle and Its Long Shadow," by Byron Farwell, 1990; "Battle at Ball's Bluff," by Kim Holien, 1985; "The Battle at Ball's Bluff," by William Howard, 1994; an autobiography by Eppa Hunton, 1933; Ball's Bluff and the Arrest of General Stone in "Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, II," by Richard Irwin, 1887; and "The Battle of Ball's Bluff," by Joseph Patch, 1958.

October 2001

Copyright © Eugene Scheel