ON THIS PAGE

Forces March Through Loudoun County

What a wild set of Creatures our English Men grow into when they lose Society

Route Through Western Loudoun

Ambushed by French and Indian Troops

General Braddock's March Through Loudoun in 1755

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

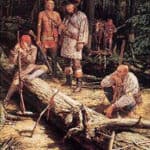

Throughout April 1755, 700 British and American soldiers fighting in the French and Indian War(Seven Years' War) trekked through what is now Loudoun County toward Fort Duquesne, Pa., on a mission to drive the French and allied Indians from their forts in the Ohio Valley and on the Great Lakes. They were the first large contingent of troops ever seen in the Virginia Piedmont.

The troops, commanded by Col. Sir Peter Halkett, were hoping to avenge the defeat of 22-year-old Col. George Washington at Fort Necessity, Pa., in July 1754. Washington had started the war in May 1754 by ordering his company to fire on a French detachment he thought was going for its weapons. Ten were killed, including the French commander.

"The volley fired by a young Virginian in the backwoods of America set the world on fire," English historian Horace Walpole wrote in "History of the Reign of King George II."

Forces March Through Loudoun County

In June 1755, Halkett's Virginia troops, officially the 44th Grenadiers or Regiment of Foot, joined a second force of about 700 that had marched west through Maryland under command of Col. Thomas Dunbar. The overall commander of both forces was British Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock. Washington was now one of his scouts.

Each command had augmented its forces with conscripts. Fairfax County Sheriff Daniel McCarty recruited 200 for Halkett, mostly former convicts and poor tenants. Non-British recruits had to be Protestants, at least 16 years old and "straight and well made, broad shouldered . . . [and] measure 5 Feet 5 without shoes."

Halkett's brigades marched out of Alexandria between April 9 and April 26 via what are now Braddock Road, Seminary Road, Route 7 and Old Courthouse Road. Their first overnight stop was at the originl Fairfax County courthouse near Tysons Corner, 18 miles from Alexandria by Halkett's reckoning.

On the second day, the contingent veered south from Route 7 at what is now Sugarland Road, traveling 12 miles before overnighting at Coleman's Ordinary, an inn. It was the group's first stop in the future Loudoun County, which would split from Fairfax in 1757.

Halkett's orderly book, written by scribe Daniel Disney, described the stop as "Mr. Coleman's on Sugar Land Run where there is Indian corn etc." Parts of the inn's foundation remain, along with vestiges of the Coleman Graveyard.

After fording the run, the troops continued west through today's Sterling Park on Sugarland Road and Juniper Avenue and then through Claude Moore Park on one of three sections of the "Braddock Road" in Loudoun still in a nearly original state. Westward, via Maries Road and routes no longer in existence, the soldiers cut back to Route 7, probably west of today's Belmont manor house.

Halkett's forces spent their third night at "Mr. Minor's," an inn owned by Nicholas Minor where the Days Inn now stands on East Market Street. They had covered an additional 15 miles, including a ferriage across Goose Creek at the site of the current old Route 7 bridge.

As there was always fear of an attack by Indians, Halkett's orderly book noted: "All the Tents to be piched upon the left of the Artillery Immediatley. 1 Corpl & 8 men to mount Guard & to put two Centrys upon the Forrage one upon the Rear of the Artillery & Baggage. The Officers Servts to Attend immediatley to get Forage for Their Masters Horses. The Engineers & Pioners to march to morrow at 8 oClock. "

The password that night was "Braddock," and the next day it was "Ohio."

What a wild set of Creatures our English Men grow into when they lose Society

A letter sent from Minor's by a British officer, who wished to remain anonymous, to a friend in London gave the first detailed description of the eastern Loudoun countryside: "The Fields . . . instead of ploughed Grounds or Meadows, they are all laid out in Hillocks, each of which bears Tobacco Plants, with Paths hoed between. . . .

" And all their Culture runs upon hilling with the Hoe, and the Indian Corn grows like Reeds to eight or nine Feet high. Indeed in some parts of the Country Wheat grows, but Tobacco and Indian corn is the chief [crops]. . . .

" Their Cattle are near as wild as Deer; a Cow-pen generally consists of a very large Cottage or House in the Woods, with about four-score or one hundred Acres, inclosed with high Rails and divided, in a small inclosure they kept for Corn, for the Family, the rest is the Pasture; . . . they may perhaps have a Stock of four or five hundred to a thousand headof Cattle belonging to a Cow-Pen. . . .

" The Keepers live chiefly upon Milk . . . Whey, Curds, Cheese and Butter, they also have Flesh in Abundance such as it is, for they eat the old Cows and lean Calves that are like to die. The Cow-Pen Men are hardy People, are almost continually on Horseback, being obliged to know the Haunts of their Cattle.

" You see, Sir, what a wild set of Creatures our English Men grow into when they lose Society."

Route Through Western Loudoun

Colonel Sir Peter Halkett fought in the French and Indian War in the British 'Colonies' in the U.S. this was known as the "French and Indian War". In the U.K, it was the "Seven Years War" . Sir Peter was shot and killed during the Battle of Duquesne (also known as Braddock's Defeat) on July 9, 1755, near what is now called Pittsburgh, PA. His son, Lt. James Halkett, saw his father get shot and ran to his aid, when he was also shot and died, alongside his father. Also of interest, there was a young Lt. Col. on Sir Peter's staff who is somewhat familiar to us... his name was George Washington. (Needless to say, Lt. Col. Washington survived the battle). Two years after "Braddock's Defeat", another of Sir Peter's sons, Major Francis Halket went with a detachment to provide proper burials for their fallen countrymen. A now-friendly Indian told of two British officers being felled at the foot of an unusual looking tree and was able to locate the tree. It was there that Major Francis Halkett was able to identify the remains of his father and brother, and was able to give them a proper Scottish burial with Tartan and Pipes.

From what is now Leesburg, Halkett's brigades took two routes to their next stop, Edward Thompson's plantation. One route was Dry Mill Road and Route 9. Early 20th-century postcards from Paeonian Springs still cite the village as being on the "Braddock Road."

A second route took a rougher course, today's Old Waterford and Old Wheatland roads, both yet unpaved and good examples of a Colonial path, though a bit wider and deeper on the hills than they were in 1755.

J.W. Reid, a South Carolina soldier camped at Belle Grove on the Old Waterford Road in July 1861, described this "camping ground of General Braddock" as "a beautiful grove of oak, hickory and other forest trees" five or six acres in size. The grove, now part of Morven Park, still fits that description.

On the Old Wheatland Road, another way stop for Halkett's men mentioned by old-timers, was a huge white oak at the northwest corner of Jack Evans's farm. Known as the "Braddock Oak," the tree came down after Tropical Storm Agnes in June 1972.

Two miles west of the Braddock Oak, Halkett's orderly book noted "Mr. Thompson's the Quaker, wh[ere] is 3000 wt. corn."Washington had recommended that stop, having stopped there on his journey to Fort Necessity.

An entry in the orderly book reads: "A serjt & 12 men to Mount the baggage Guard and Centrys to be posted on the waggon horses. The Genl [Halkett] to beat at 3 oClock at which Time the Horses are to be put to the waggons. The Waggoners to be told if Any of their horses were not Ready when the Troop Beats or any that [h]as horses wanting will be Punished." In early June 1755, a supply train followed Halkett's forces. Attached to the train was a wagon carrying "Mrs. Browne" or "Madame Browne," a widow accompanying her brother, a commissary officer. Her first name was kept anonymous by the recipient of her diary of the journey. Browne was the only person to write of the trek through western Loudoun.

" We halted at Mr. Minor's," she wrote. "We order'd some Fowls for Dinner but not one to be had, so was obliged to set down to our old Dish Gammon [ham] & Greens." The previous evening they had eaten ham for dinner at Coleman's Ordinary.

An officer and a parson, whom she identified as Mr. Adams, "replenish'd their Bowl so often that they began to be very joyous, untill their Servant told them that their Horses were lost; at which the Parson was much inrag'd and pop'd out an Oath."A Mr. Falkner then said, "Never mind your Horse, Doctor, but have you a Sermon ready for next Sunday?"

Browne then tells of the parson becoming flirtatious. "I being the Doctors country woman, he made me many Compts. [compliments] and told me he should be very happy if he could be better acquainted with me, but hop'd when I came that way again I would do him the Honour to spend Time at his House."

The party chatted until 11. "I took my leave," she wrote, "and left them a full Bowl before them."

Next day, the party "March'd 14 Miles and halted at an old sage Quaker with silver Locks." There, Thompson's wife "accosted" Mrs. Browne "in the following manner," to use Browne's words.

" 'Welcome Friend set down,' Mrs. Thompson said. 'thou seem's full Bulky to travel, but thou art young and that will enable thee. We were once so ourselves but we have been married 44 Years & may say we have lived to see the Days that we have no Pleasure therein.'

" We had recourse to our old dish Gammon, nothing else to be had," Browne wrote. "But they said they had some Liquor they call'd Whisky which was made of Peaches. My Friend Thompson being a Preacher, when the soldiers came in as the Spirit mov'd him [Thompson], held forth to them and told them the great Virtue of Temperance. They all stared at him like Pigs."

Regarding her overnight stay, "many close Companions call'd Ticks deprived me of my Nights Rest." Next day, to prepare for the journey ahead, the party baked bread, boiled beef and prepared two chickens.

From the Thompsons, they obtained milk and water, the latter Thompson called a "fine temperate Liquor." Returning to their wagons, Browne wrote that several items had been stolen, including two hams.

Upon leaving "my Friend Thompson, who bid me farewell," Browne and her wagons encountered "a great Gust of Thunder and Lightning and Rain, so that we were almost drown'd," as they "forg'd through" the North Fork of Catoctin Creek and "pass'd over the Blue Ridge which was one continual mountain for 3 Miles."

The party crossed the Shenandoah River via John Vestal's ferry and stayed that night at Gersham Keyes, "a fine Plantation," Browne noted. They had two chickens for dinner, and then, Browne recorded, "the soldiers desired my Brother to advance them some Whisky for they told him he had better kill them at once than to let them dye by Inches, for without they could not live. He complied with their Request and it soon began to operate; they all went to dancing and bid defiance to the French."

Ambushed by French and Indian Troops

At Midday June 26, 1755, General Braddock's scouts and guides working in advance of the main column, happened upon a site that was occupied the night before by 150 to 200 French and Indians. The following two accounts recorded by Captain Orme and an unknown British officer tell of the tree taunts observed there.

"They (The Indians) had Stripped and painted some trees, upon which they and the French had written many threats and bravados with all kinds of scurrilous language." - Captain Orme

"They had drawn many odd figures on ye trees expressing with red paint. Ye scalps and prisoners they had taken with them." - Unknown British Officer

(Taken from "Braddock's Defeat", by Charles Hamilton.)

Their dance may have been their last, for on July 9, 1755, 300 French and Indians ambushed Braddock's force of 1,300 advancing upon Fort Duquesne. About 700 British and American soldiers were killed or wounded.

Braddock and Halkett were killed. Washington was wounded, and Mrs. Browne's brother died of disease a few days after the battle.

Reporting Braddock's defeat to acting Virginia Gov. Robert Dinwiddie, combatant John Ashby of Fauquier County told of settlers "pouring over the gap" (where Route 50 crosses the Blue Ridge) that took his family's name.

Until February 1763, when the Treaty of Paris ended the French and Indian War, land prices and sales plummeted in western Loudoun and Fauquier. Many expected Indian attacks, and some settlers left their farms for safer regions of Tidewater Virginia.

In autumn 1758, a wooden stockade enclosed Loudoun's first courthouse complex at Leesburg. The attacks never came.

The most accessible book detailing Braddock's expedition is Andrew J. Wahl's "Braddock Road Chronicles 1755," Bowie, Md, Heritage Books, 1999. This work has the best bibliography. Also of note, Ross Netherton's "Braddock's Campaign and the Potomac Roads West," Falls Church, Va., Higher Education Publishing, 1989.

For the Virginia routes, see Walter S. Hough's "Braddock's Road Through the Virginia Colony," Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society, 1970.

For the Maryland routes, see Curtis L. Older's "The Braddock Expedition and Fox's Gap in Maryland," Westminster, Md., Family Line Publications, 1995. Also, Allan Powell's "Maryland and the French and Indian War," Baltimore, Gateway Press, 1998.

Copyright © Eugene Scheel