History Affects 1860 Presidential Election Vote in Loudoun County and Northern Virginia

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

See also, A County Divided - Loudoun County and the Civil War »

Lincoln Was No Favorite At the Polls

In the 1860 presidential election, Fauquier and Loudoun county voters cast only 12 ballots for the winner, Abraham Lincoln. The previous year, an unexpected revolt had frightened or worried many people who might otherwise have voted for the man who saved the Union and brought an end to slavery.

Loudoun and Fauquier were at the time the wealthiest counties in Virginia. Agricultural land sold for $20 an acre and more, the most expensive in the state. Corn, wheat and grain harvests were unsurpassed in the commonwealth and commanded high prices at the seaport of Alexandria, linked to the hinterlands by three well-kept toll roads.

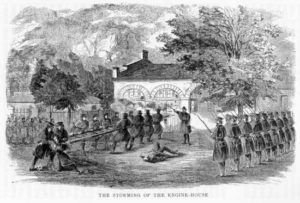

Prosperity continued after John Brown's Oct. 16, 1859, raid on Harper's Ferry. Brown's aim was to liberate and arm area slaves and set up an autonomous realm for them in the mountains of Maryland and western Virginia, where there were few slaveholders.

That such an insurrection could happen only a half-mile from the Loudoun border — even though it lasted just 2 1/2 days and involved 22 insurgents — led to an abrupt change in the county's political climate, from apathy to uncertainty. There was outright fear in the Between the Hills and Lovettsville areas, a few miles from the ferry.

Fauquier's reaction was more subdued, being 25 miles from the ferry at its closest point, the village of Paris. Furthermore, Fauquier's military companies were commanded by such experienced leaders as Brig. Gen. Turner Ashby and Capt. John Scott Jr.

Gov. John A. Wise ordered three Fauquier and two Loudoun companies (about 250 men total) to the ferry. They spent most of their time drilling and on guard duty until their tour ended in mid-December with an oyster and champagne supper at Charles Town, where Brown had been tried and imprisoned and hanged Dec. 2. When the Fauquier companies returned home, they were feted by the women of Warrenton with a pre-Christmas ball at the old Warren Green Hotel.

Many northern newspapers and magazines wrote editorials lauding Brown's attempt to free slaves. But the Democratic Mirror, Loudoun's most widely read local newspaper, wrote in an October editorial: "Upon calm consideration of this affair . . . it was one of the most complete and fearful plans for revolution. . . . We think we see in it the direction and control of more intelligence." The suggestion was that others, specifically northerners, had masterminded the attack.

In his 1976 book, From Frontier to Suburbia, Northern Virginia historian Charles P. Poland Jr. analyzed Loudoun's reaction to Brown's raid from October to December 1859.

Poland cited one Mirror article about meetings in Hillsboro and Lovettsville where he said participants "denounced and attempted to prohibit peddlers, book agents, travelers, and vendors of goods from traveling through the county."

Their intent, Poland said, "might be to incite slave insurrections." The Mirror also noted that Hillsboro area women had accused schoolteachers of provoking slaves to follow Brown's example.

The Alexandria Gazette, which was widely read in Loudoun and Fauquier, constantly commented in its editorials in November and December 1859 that the aim of abolitionists such as Brown was to end slavery, even if that meant insurrection or war. The term "abolitionist" was used then as loosely as "liberal" is today.

The Gazette reprinted the jottings of a Washington Star correspondent who described the sentiment in Northern Virginia in November 1859: "This excitement is not a wild one. . . . It is a calm and clear sentiment in favor of a speedy end of the Government of the United States, if it is to continue to be a means through which parties from the North may steal into the South."

To make sure that no enemies would cross into Loudoun from the north, the county had raised and equipped eight military companies by 1860.

"[Loudouners] are armed to the teeth and ready for war! Being determined to defend our institution from all assaults of abolitionists if need be, at the point of bayonets and cannon's mouth," said a Democratic Mirror article cited by Poland.

Fauquier's elected officials also became cognizant of the barrage of warlike news. By 1860, its county court placed four well-armed volunteer military companies on active duty. Of the court's $35,341 budget for that coming fiscal year, $20,000 went to fund the military companies. At the time, the court performed functions similar to today's Board of Supervisors.

Fauquier's court reminded the military companies "to use the utmost prudence and humanity in the discharge of their duties" and to allow deputized patrols of men "only when and where necessary," according to court minutes.

A personal thought — one of few surviving in print — appeared in the diary of Rebecca K. Williams, a Waterford Quaker. Excerpts were published in the Waterford Foundation's 1996 book, "To Talk Is Treason."

"We have now started upon the year 1860," she wrote. "What scenes are hid behind the curtain of time no eye can see. The future politically looks threatening. May the Almighty Father avert the evil and imbue the hearts of our Legislators with wisdom and right understanding to direct the affairs of the Nation."

Five presidential nominating conventions met between April 23 and June 28, 1860.

The Democratic Party met first but adjourned after southerners called for a platform that would have the federal government protect slavery in U.S. territories.

Minus the southern wing, the party met again two months later. It nominated moderate Stephen A. Douglas for president, and the party platform called for either the U.S. Supreme Court or a popular vote in the territories to determine whether each territory would allow slavery.

The breakaway pro-slavery Democrats met June 28 and nominated John Cabell Breckinridge, a slave owner from Kentucky who was vice president under sitting President James Buchanan. Their platform called for federal protection of slavery in the territories.

Another new party, the Constitutional Union Party, nominated John Bell, a Tennessee slave owner who was considered a moderate on the subject. The party evaded the slavery issue.

The Republican Party, formed in 1856, nominated Abraham Lincoln of Illinois. The party platform called for abolition of slavery in the territories.

Lincoln had a family connection to Fauquier, though it was not then considered one to boast about. David Herbert Donald, in his 1995 biography "Lincoln," quotes Lincoln as telling his law partner, William H. Herndon, in the early 1850s that Lincoln's mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, was "the illegitimate daughter of Lucy Hanks and a well-bred Virginia farmer or planter."

Donald quotes Lincoln as saying in 1860, when his friends asked him for autobiographical information that might boost his chances for the presidency: "My parents were both born in Virginia, of undistinguished families -- second families, perhaps I should say."

Nancy Hanks's father remains unidentified, but she was baptized in 1778 in the waters of Broad Run close to Broad Run Baptist Church. The church then stood atop Saint's Hill, a mile north of present-day New Baltimore.

Loudoun had voted for Whig Party candidates since 1832, including Millard Fillmore, who was personally opposed to slavery but preferred compromise rather than risk civil war, in 1856. Fillmore had been a Whig and served as that party's president from 1850 to '53. The Whigs were for protective tariffs to encourage the growth of industry and for strong transportation networks.

As the slavery issue became paramount, northern Whigs joined the Republicans in 1856, and southern Whigs joined the Democrats. The Whigs succumbed, to be resurrected in 1860 as the Constitutional Union Party. Its platform was "The Constitution of the country, the Union of the States, and the enforcement of laws." Bell, the Unionist candidate, was a clear favorite in Loudoun.

They had also been dominant in Fauquier since 1832, but in 1856 the county voted for Buchanan, a Democrat who was considered a stronger proponent for slavery than Fillmore. Fauquier had more slave owners than Loudoun; 48 percent of its population was enslaved compared with Loudoun's 25 percent.

Newspapers, especially in the South, predicted that if Lincoln won the election, there might well be war. Editorials pointed to such speeches as the one he gave at Alton, Ill., in October 1858: "The sentiment that contemplates the institution of slavery in this country as a wrong is the sentiment of the Republican party. They look upon it as a moral, social, and political wrong."

Lincoln and his party were often called "Black Republicans" by newspaper writers who were either neutral regarding the slavery issue or pro-slave.

On Election Day, Nov. 6, 1860, all white males 21 and older who had lived in the state for two years or more were eligible to vote. Turnouts in Loudoun and Fauquier were the largest ever, and there were no surprises among the three candidates on the ballot, except for the top-heavy vote for Bell in Loudoun.

His 2,033 votes, compared with Breckinridge's 778 and Douglass's 120, indicated that many Quakers and people of German descent, almost all of whom were opposed to slavery, wanted to maintain the prosperous status quo. Thus, they chose to vote for Bell, the moderate candidate, rather than the avowedly anti-slave Lincoln, for they thought he might act rashly and disturb southern trade with Europe and the North.

In Fauquier, Breckinridge defeated Bell 1,027 to 789, with Douglass garnering 39 votes. Bell won in the northern county precincts of Landmark, Paris, Salem and Upperville. As with the prosperous farmers and plantation owners of Loudoun, their Fauquier counterparts did not want to risk a change in an accepted way of life.

Breckinridge's strength came in the county's center and south, especially in Liberty and New Baltimore, where farms were small and plantations fewer than in the upper county.

Lincoln, whose name did not appear on the ballot in Virginia, received 11 votes in Loudoun and one in Fauquier. The Fauquier vote was cast by Henry Dixon, a testy militia colonel who lived at Vermont, a farm south of Salem in the valley bearing his family's name. He went to the polls with a pistol in his belt, and as there was no secret ballot, announced he had voted for Lincoln when he left the polling place. Many in the neighborhood said Dixon got what he deserved when he was killed in a street duel in Alexandria after the war.

Loudoun's precinct returns have not been found, but Taylor M. Chamberlin, in his 2003 book, Where Did They Stand?, uncovered a 1923 Loudoun Times newspaper clipping in which "One Who Was There" identified nine men and a probable 10th and 11th who voted for Lincoln. The 11 usually voted in the Lovettsville, Purcellville and Waterford precincts.

Old-timers recalled that Robert Johnson, a possible voter for Lincoln at the Lovettsville precinct, was armed with a shotgun to defend a Lincoln banner he had raised near the polling place.

Absent from the list of Lincoln voters cited by "One Who Was There" were the county's two most prominent anti-slavery voices, Samuel Janney, an educator and Quaker historian, and Yardley Taylor, a cartographer, geographer and horticulturist. Both men had been constantly accused of assisting escaped slaves.

An unexpected strong Republican vote came from the Occoquan precinct in Prince William County. Fifty-five men in that milling town and seaport, home to some Quakers, voted for Lincoln. Before the election, they had raised a pole flying a Lincoln banner. It angered so many people that the county court authorized a militia to tear it down.

The other 13 counties and three independent cities of Northern Virginia and the lower Shenandoah Valley gave Lincoln a total of 40 votes. He received 1,887 in the state, mostly in the mountainous counties of western Virginia. Breckinridge won in Virginia by 156 votes, his strength coming from the southern part of the state.

On March 7, 1861, Catherine Barbara Broun, a Middleburg housewife, wrote in her diary: "We are all in great distress now about the state of the country. Mr. Lincoln was inaugurated this week (Black Republican). We greatly fear Civil War."

Copyright © Eugene Scheel