History of Loudoun's Limestone Overlay District

by Eugene Scheel with edits

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

Board establishes Limestone Overlay District »

Benjamin Latrobe’s Potomac Marble Quarries »

In a 1699 northward journey to meet with American Indians, adventurers Giles Vandercastel and Burr Harrison described a landscape feature unique to Piedmont Virginia and Maryland. As they trekked close to the Potomac River north of what is now Leesburg, they passed "very Grubby and greate stones standing Above the ground like heavy [hay]cocks."

Those strewn-about mammoth pebbly limestone outcrops, embedded in a sandy mortar, are the residues of successive submergences at the bottom of Triassic seas some 190 million years ago. Through the ensuing ages, precipitation mixed with the air's carbon dioxide and formed a mild carbonic acid, which has eroded the landscape, forming subterranean sinkholes, passageways and caverns.

"It's like a sponge with holes," said Alex Blackburn of the county's Department of Building and Development, adding that many areas are susceptible to collapse and that underground passageways can carry pollutants into neighboring wells.

Don Michael, a well driller whose bits have pierced area house sites, said: "It's like a maze underneath there. Water travels so fast it doesn't have a chance to get purified. A cavern can then fill in with a pastelike mud, thick as mashed potatoes -- the residue of dissolved rock that doesn't get carried off with the water."

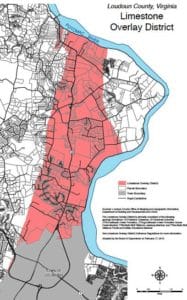

To protect homeowners, Loudoun County recently created the limestone overlay district from Leesburg northward and west to the base of Catoctin Mountain. Before construction, the ordinance requires X-rays of the ground to locate voids and dictates setbacks from these above- and below-ground sinks. The ordinance is not in effect in Leesburg.

Often bordering the sinkholes are the irregular outcrops of limestone described in 1699 and a century later known as Potomac marble or calico marble.

From 1793 to 1817, when the U.S. Capitol was built and then rebuilt after the British burned it in 1814, the Potomac marble was delivered the 40 miles, then cut, polished and put in place. Visitors continue to admire the stone, as lustrous as real marble, used for the columns in the Capitol building.

One Leesburg quarry where the stone was mined is now near the town's Isaak Walton Park. The other quarry, closer to downtown, was mined by the Leesburg Lime Co. from 1888 to 1945, when drillers hit an underground stream. The cavity filled within two days and shortly became the local swimming hole. From 1998 to 2000, the old quarry was drained and crammed in with soil and rock, and became a parking lot.

As large blocks of readily chiseled building stone grew scarce, the rocks' main use became agricultural lime, a mainstay of the old Leesburg Lime Co. and of a survivor, an immense three-hole lime kiln run by Addison "Ad" McKimmey for the greater part of its existence from 1870 to 1910. It's a restorable ruin, on Saint Clair Lane north of Lucketts. The lime produced by the burn, when spread across fields and rained upon, changed into slaked lime, which reduced soil acidity.

Enterprise of a different sort challenged three teenagers at Rockland, a farm north of Leesburg, in the 1880s. In the reminiscences of one boy, Harry Rust: "We were always looking for caves in the hopes of discovering a big one which they could charge admission and get rich in that way."

They were shown where Big Cave on the farm was but couldn't get to it. So 400 feet away, they entered Eddie's Cave, named for one of the brothers, and, at the end of a second "good-sized room," began digging into the soil. They never reached the big cave. Years later, Rust wrote of their foolishness: "Settlement might have occurred, in which case they would have been buried alive."

The limestone region's most famous caves are underneath Carlheim, a 32-room Leesburg mansion, now the Aurora School. In 1872, as Carlheim neared completion, builder James L. Norris wrote owner Charles Paxton, informing him that there were three large caverns at the bottom of an 80-foot well. In the letter, Norris's workman described the caverns as a "rather frightful looking place with an air of mystery and dread which he cannot shake off."