'Loudoun' Lee Made A Name for Himself

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

At the main terminal of Dulles International Airport, Mary S. Browne, regent of the Cameron Parish Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, unveiled a bronze plaque to Francis Lightfoot Lee. The plaque says Lee signed the Declaration of Independence, was a Revolutionary War patriot and once owned part of the airport's land.

The event was the culmination of a 23-year quest by the DAR chapter to honor Lee, who, besides being one of the nation's founding fathers, guided Loudoun County in its formative years.

Lee was the fifth of eight children born to Thomas![]() and Hannah Lee of Stratford Hall in Westmoreland County. He was born in 1734 into wealth, as his father held the preeminent post of councillor to the governors of Virginia. Young Lee was called "Frank" by his siblings and friends.

and Hannah Lee of Stratford Hall in Westmoreland County. He was born in 1734 into wealth, as his father held the preeminent post of councillor to the governors of Virginia. Young Lee was called "Frank" by his siblings and friends.

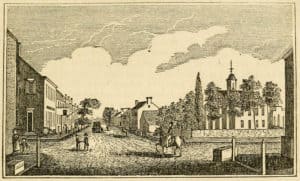

"Central View of Leesburg", an engraving from Henry Howe's Historical Collections of Virginia (1845)

In 1749, the British crown bestowed on Thomas Lee the title of acting governor of Virginia, which he held until his death a little more than a year later. Frank, then 16, remained at Stratford Hall but had inherited more than 7,000 acres in Fairfax County, so he began planning a move northward when he "achieved his majority" -- the Colonial phrase for becoming 21.

Lee had his choice of two tracts, several miles apart, and chose the upper one, 3,184 acres in a newly created county called Loudoun, which split from Fairfax in April 1757. Thomas sixth Lord Fairfax had granted Thomas Lee the acreage in 1724, when it was described simply as being on the Stallion Branch of Horsepen Run.

Eastern Loudoun historian Carl Franklin Macintyre was able to plat the acreage, in the mid-1980s, from the meager description above, a testament to his varied talents. Defining the tract's boundaries was necessary to prove to airport authorities that Francis Lightfoot Lee owned land now encompassed by the airport. The house Lee lived in no longer stands, and nobody knows precisely where it stood.

Leesburg was originally named George Town after King George II of England. The town was renamed Leesburg after Thomas Lee who was governor of Virginia from 1749 until 1750. Many of the original houses and shops are still being used in the historic section of Leesburg. Every August, Leesburg hosts an 18th-century market fair complete with living history players

Lee moved to Loudoun because he wanted to enter public service, and a new county provided that chance, especially if one's surname was Lee. For credentials, he had been tutored by several clergymen and had had the benefit, an early biographer noted, of a family library made up of "the best editions of all the great British writers, in every branch of science, poetry and belles-lettres."

Lee initially held two important county positions, both given to him by the governor's council, of which his father had been a longtime member. In December 1757, he became "First Justice" of the initial 13-man county court, and by that date he also was county lieutenant, meaning he commanded the Loudoun militia.

With Indian incursions just to the west of Loudoun, and the Seven Years War (1756-1763) against the French in its infancy, the county lieutenant's post was crucial. It also positioned him well politically, because the county lieutenant chose his junior officers, all of whom could vote.

Thus it was no surprise, that in July 1758, freeholders of Loudoun elected Lee to the House of Burgesses, Virginia's governing assembly, as a representative from the lower part of county. James Hamilton, an established citizen who lived between present-day Hamilton and Waterford, represented upper Loudoun.

Lee's siblings, taken by Lee's sudden rise to stardom on the Piedmont Virginia frontier, bestowed a new nickname, "Loudoun," upon him. In official matters, however, he was always referred to as Francis Lightfoot Lee, the designation he preferred.

The burgesses convened at Williamsburg, Virginia's Colonial capital, in September. There were five Lees in the body, including two of Francis's older brothers -- Thomas Ludwell Lee of Stafford County and Richard Henry Lee of Westmoreland County.

One of the assembly's first acts was to establish Leesburg as the courthouse town of Loudoun. Before the 1970s, every history of Loudoun and every Leesburg tourist brochure touted Francis Lightfoot Lee as the town's namesake or probable namesake. As a Loudoun representative, he introduced the bill that established the town, but it would have taken the utmost gall for a freshman legislator to name the town for himself, and Lee was a modest man.

Leesburg was almost certainly named for his father, Thomas Lee, and if not, for the Lee family. That is supported by the fact that Thomas's eldest son, Philip Ludwell Lee, a former burgess, was the bill's patron on the governor's council. More than 100 years later, Thomas Lee's great-granddaughter, Matilda Lee Love, wrote in her reminiscences that she had always heard that Leesburg was named for Thomas Lee.

As a burgess, "Loudoun" Lee served on committees dealing with "Propositions and Grievances," "encouraging Arts and Manufactures" and "Privileges and Elections." He also sat on committees of brief duration, some dealing with concerns of war and hostile Indians. These various appointments, through 1766, are noted in Colonial historian John Phillips's epic 1996 summary of Loudoun's first decade, "The Historian's Guide to Loudoun County."

In March 1759, Lee served on a committee to review Loudoun's request to pay public fees and levies with money, rather than with tobacco, the commodity of payment in most Virginia counties. Six counties already had adopted "money fees," and Lee successfully placed Loudoun -- whose agricultural base consisted of corn, wheat and small grains instead of tobacco -- with that group.

In December, the burgesses passed a sweeping act allowing all counties to pay levies in tobacco or money, the latter based on the price of a pound of tobacco.

On the debit side of Lee's tenure as a Loudoun burgess, which lasted until 1769, his 1987 biographer, Alonzo Thomas Dill, recounts that Lee was often absent from assembly sessions and, when present, found them boring. He confided to younger brother William that "the people [of Loudoun] are so vex'd at the little attendance I have given them that they are determined it seems to dismiss me from service, a resolution most pleasing to me."

Such apathy coincided with his concerns for Virginia's grievances against Great Britain, which began in earnest during the Stamp Act crisis. That act, passed by Parliament in March 1765, decreed that colonists had to apply stamps to nearly every official document and publication. The act's purpose was to raise money to support British armies in North America, even though the war against the French had ended in 1763.

As a protest against the Stamp Act, county courts in Virginia did not meet from early winter 1765 until early summer 1766. In February 1766, Francis Lee's brother Richard Henry Lee presented his "Westmoreland Resolutions" to 115 Virginians, Francis Lee among them, and all of them signed. The resolutions threatened "Death and Disgrace" to persons paying the stamp tax.

That April, Lee placed an ad in the Williamsburg newspaper, the Virginia Gazette, denouncing the tax by requesting "a Favour of all his Acquaintances, that they will never take any LETTER directed to him out of the POST-OFFICE, as he is determined never willingly to pay a Farthing of any TAX laid upon this COUNTRY, in an UNCONSTITUTIONAL MANNER." In those days, the recipient who picked up the letter paid the postage. The Stamp Act was repealed that spring.

The ad marked Francis Lee as one of a group of radicals asserting the colony's right to formulate its laws, independently of Parliament. To this effect, he was appointed in 1770 to a prestigious committee of burgesses "to protest British policies."

By then, his marriage to Rebecca "Becky" Tayloe, a Williamsburg belle, was a year old, and he had moved to Richmond County, where he served as a burgess from 1769 to 1776.

During those years, Francis Lee played a behind-the-scenes role in drafting documents and creating committees that led to the colony's break from Britain. In 1773, he helped to organize Virginia's Committee of Correspondence, the first of many colonies' groups of the same name. These committees kept in touch with other colonies in their struggles for economic and political rights.

In 1774 and 1775, he was Richmond County's delegate to the first and second Virginia conventions -- the former forbidding import of British slaves or goods and export of the colony's goods to Great Britain; the latter authorizing the arming of each county's militia.

In those years, his fellow burgesses also chose Francis Lee as one of two Virginia representatives to the first and second continental congresses. John Adams, who would become the second U.S. president and was a delegate to those congresses, described Lee as "a man of great reading, well understood, of sound judgment and inflexible perseverence in the cause of his country."

Francis Lee's last political act was characteristic of his understatement. A local lawyer, John Warden, had drawn a crowd outside the Richmond County courthouse as he was denouncing the proposed U.S. Constitution.

Lee, passing by, was asked what he thought and replied that he was old -- 53 in 1787 -- and didn't read much anymore. He said he knew only that "General Washington was for it and John Warden was against it."

In 1795, he wrote his brother William, "The world seems crazy, and we old people must scuffle with it, as well as we can, for our few days of existence." Francis Lightfoot Lee and his beloved wife died within 10 days of each other, in January 1797, at Menokin, their Richmond County home.

Then the story returns to Loudoun, for as the Lees had no children, his estate passed to nephews. Ludwell Lee, son of Richard Henry Lee, who also had signed the Declaration of Independence, inherited the Loudoun land. He sold the property shortly and, with the money, began to construct his magnificent Belmont plantation east of Leesburg.

Mark Twain wrote a brief essay about Francis Lightfoot Lee's life in 1877. It began: "This man's life-work was so inconspicuous that his name would now be wholly forgotten, but for one thing -- he signed the Declaration of Independence."

Twain continued with phrases describing Lee: "He dealt in no shams. . . . His course was purity itself, and he retired unblemished when his work was done. He retired gladly. . . . He did no brilliant things, he made no brilliant speeches; but the enduring strength of his patriotism was manifest.

"Since then we have Progressed one hundred years. Let us gravely try to conceive how isolated, how companionless, how lonesome, such a public servant as this would be in Washington today."

Copyright © Eugene Scheel