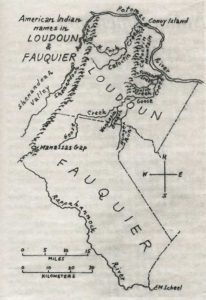

Indians Left Their Mark in Naming Landmarks in Loudoun County

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

Indians Mounds in Loudoun County »

The last American Indians left Loudoun and Fauquier counties almost 300 years ago, and only a few names they used to describe their landscape survive. They co-existed with the first few European trappers and adventurers in the area for only about 30 years before the Indians agreed to move west of the Blue Ridge in 1722.

Ethnologists from the Smithsonian Institution have told me that most of these surviving names were of the Algonquin tongue. The spellings have varied because the Europeans who first heard the words often spelled them differently.

A European would point to a feature, such as a mountain or stream, and the Indian would say its name. Only upon repeated pointings to similar features would the European be certain that, for instance, "Potomac" meant a particular river, not just any large river or body of water.

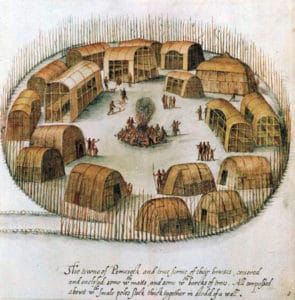

Potomac was one of two Algonquin names for the river forming the northern boundary of Virginia, and it meant "great trading place" or "place where people trade." The Algonquin bartered along its shores, especially near Point of Rocks, where many islands make the river fordable or easily navigable by canoe or raft. The Algonquin traded with Sioux who lived to the west and migrating Susquehanna and Iroquois Indians.

In general, the names Indians used have been simplified through the years. The Potomac's common spelling through the 18th century was "Patowmack." An earlier spelling was "Patawomeke."

The Indians observed flocks of geese and other birds resting on the Potomac's waters, so they also called the river "Cohongorooton," meaning "river of geese or swans." Their plumage was prized for ceremonial wear.

Similarly, Goose Creek, the largest Loudoun tributary of the Potomac, was called "Cokongoloto," meaning "creek or stream of geese or swans."

Such complicated and discordant names quickly disappeared from the Europeans' vocabulary. But three major tributaries of Goose Creek still have Indian names.

Tuscarora Creek, which flows through Leesburg, is named for the Tuscarora Indians, who passed through the area on their way to central New York from 1715 to 1722 after being defeated by the British in North Carolina.

Sycolin Creek, a few miles south of Tuscarora Creek, also has varied in its spelling, from "Seagland" -- the traditional local pronunciation -- to "Seconnel." Its meaning has been obscured by time.

Wankopin Branch, which crosses Route 50 just east of Middleburg and rises in Fauquier, was named by the Piscataway Indians, who lived in the area during the 1690s and spoke the Algonquin language. The first two syllables have no known meaning, but "pin" in that language means root. In English, however, "Wankopin" is a type of water lily, and before the Piscataway moved to the Middleburg area, they lived for 60 years among English settlers in Southern Maryland.

Early deeds often spell the stream "Nankoping." Most locals used to pronounce the stream "Walkerpen" or "Wankipin," with the accent on the first syllable.

Hunger Run, a tributary of Little River, itself a branch of Goose Creek, bisects the Landmark region of northeastern Fauquier. This run also was named by the Piscataway, who, by the 1690s, spoke English.

At that time, the Piscataway moved back to the Potomac River near Point of Rocks. They had lived primarily on fish in Southern Maryland, but marine pickings were slim in the shallow streams around Middleburg. The main Piscataway settlement then became an island called Conoy, a shortened form of "Kanawha" (pronounced Kanaw), which was a Piscataway tribe. A prominent spring on the Maryland side of the island still bears the name Kanawha Spring. The 188-acre Conoy Island is readily visible to the east while crossing the Point of Rocks bridge.

Far downriver, at the present border of Loudoun and Fairfax counties, the rapids and falls just east of Lowe's Island are called "Seneca," a catchall southern designation for Iroquois, as the Seneca were an Iroquois nation. Seventeenth- and 18th-century records often spell the name "Senegar" or "Seneker."

"Rappahannock," the river forming the southern boundary of Fauquier County, means "people of the ebb and flow stream," for east of Fredericksburg, the river is a tidal stream, and an Indian grouping of that name who spoke the Algonquin language lived along the river's lower reaches.

The complicated spelling of the river led most people to call its upper reaches Hedgman's River (for early settler Nathaniel Hedgman) from about the 1730s to the 1830s. But with the formation in 1833 of Rappahannock County, Fauquier's neighbor to the west, the Indian name gradually came back into popular usage.

Catoctin, a name used for both a mountain and a stream, is indicative of the confusion that must have been evident when some European asked his Indian guide for the name of the prominent range and Potomac tributary, both of which meet the Potomac in the same location.

Did the Indian mean that "Catoctin" was the mountain, the stream or both? Smithsonian ethnologists say that the mountain range was named first and that it means "ancient wooded hill." The stream, and another by the same name, also a Potomac tributary and nearby in Maryland, followed suit. Early Loudoun spellings of the mountain and stream prefer "Kittockton," with the accent on the middle syllable.

One mountain gap, where Interstate 66 crosses the Blue Ridge, bears an Indian name -- Manassas. A historical marker at the gap notes that it might have been named for "a local Jewish innkeeper" with the biblical name Manasseh. But there would have been no one to come to the inn when the name Manassas first appeared -- on surveyor John Warner's 1737 area map. The area was not settled until a decade later.

I tend to believe that the name Manassas relates to Massanutten Mountain, the prominent range of the Appalachians to the west, quite visible from Manassas Gap. Massanutten may, in an Indian language, mean peaked mountain, locally pronounced in two syllables, "peak-id."

Other Indian lore says Massanutten stands for three tops, as the mountain has three distinct summits; old field, a reference to former fields on its slopes; or basket, as the Fort Valley separating the mountain from the Blue Ridge might be construed as having a basket-like shape.

Shenandoah, the overall name of the valley and river to the west of the Blue Ridge, also is an Indian name. Henry Heatwole's "Guide to Skyline Drive and Shenandoah National Park," a classic of its kind, gives seven meanings for the word, the most popular of which is most pleasing to the ear, "Daughter of the Stars," referring to the river's source in the mountains. Three other translations have similar meanings.

Heatwole says he thinks the most plausible meaning is from an Iroquois word meaning great meadow or big flat place. The Iroquois word, however, is "Skahentowane," and most early maps and records spell the valley and its river quite simply, either "Shenando" or "Sherando," the name of an Iroquois chief.

Copyright © Eugene Scheel