1699 Encounter With Piscataway Indians Was a First

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

Meeting the Piscataway depicts the first settlers to explore the interior of Loudoun County in 1699. Painting by William Woodward.

In 1699, two gentleman planters, Burr Harrison and Giles Vandercastel, became the first settlers to explore the interior of Loudoun County and the first to record a meeting with Loudoun's native Indians.

Remembering the oft-repeated words of her father, Burr Powell Harrison, a civil engineer born and raised in Leesburg, Dodge told me that Burr Harrison "was the first white man to enter Loudoun County, and he came to make a treaty on the governor's behalf."

In 1699, Burr Harrison and Vandercastel lived far to the southeast of present-day Loudoun County, in what was then the vastness of Stafford County. Their journey to the Piscataway village, estimated at "about seventy miles" in the adventurers' chronicle, was commissioned by Virginia Gov. Sir Francis Nicholson to assess the lifestyle, strength and motives of the Piscataway Indians.

Dodge also recalled that as a young woman, she visited Fort Evans, the home of Hayden B. Harris, and that on their stairwell, there was a rendering, in primitive style, of the meeting between Harrison, Vandercastel and the Piscataway. A fire in 1945 destroyed the painting and the home.

As recorded in the "Calendar of State Papers," a collection of Virginia's Colonial documents, Gov. Sir Edmund Andros had been concerned about accounts of "some mischiefs done in Stafford County" by the Piscataway. In October 1697, to quote Andros, that tribe, "remaine[d] back in the Woods beyond the little mountains" -- the Little River or Bull Run mountains. Archaeological excavations a few years ago indicated that their main village by the Little River was at Glen Ora farm, two miles southeast of Middleburg, in Fauquier County.

The Piscataway, who previously lived in Maryland along the shores of the lower Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay, had moved to the wilderness of the present Middleburg-Landmark area because they thought the Maryland government was going to destroy their people.

In 1697, Thomas Tench and John Addison of the Maryland Council had visited the Piscataway to persuade their chief to return to Maryland. The tribe had been valued as fishermen.

About the Conoy (Piscataway) Indians

These Indians were closely related to the Delaware and Nanticoke tribes. They originally inhabited the Piscataway Creek in Southern Maryland but were forced to move to the Potomac region because of constant attacks by the Susquehannocks. In 1701, they attended a treaty signing with William Penn and moved into Pennsylvania under the protection of the Iroquois nation, becoming members of the "Covenant Chain." The Covenant Chain was a trade and military alliance between the Iroquois and the non-Iroquoian speaking tribes conquered by the former. The conquered tribes had no vote or direct representation in the Iroquoian Council and all relations with the Europeans were handled by the Iroquois. In return the Iroquois agreed to protect the members from intertribal warfare. The Canoy settled along the southern Susquehanna River in a region once occupied by the Susquehannock. Once in Pennsylvania, they continued to spread northward and established a town in 1718 at the mouth of the Conoy Creek. The tribe continued to move and finally settled on an island at the mouth of the Juniata River.

The culture of the Conoy or Piscataway Indians was said to resemble that of the Powhatan Indians of Virginia. They lived in communal houses which consisted of oval wigwams of poles, covered with mats or bark. The women of the tribe made pottery and baskets, while the men made dug-out canoes and carried the bows and arrows. They grew corn, pumpkins, and tobacco. Their dress consisted of a breech cloth for the men and a short deerskin apron for the women. The Piscataway were known for their kind, unwarlike disposition and were remembered as being very tall and muscular.

Tench and Addison received no promises that the Indians would return and got lost on their way back to Maryland. Somewhere in the upper waters of the Accotink, in present-day Fairfax County, they came upon Giles Vandercastel's plantation. After hearing the story of their visit, he told Tench and Addison the best way to return to Maryland.

The Piscataway then moved from Fauquier to Loudoun and the islands of the Potomac in the vicinity of Point of Rocks. The name of the prominent tributary of Little River -- Hunger Run -- gives a hint as to why the tribe relocated: Too few fish swam in the Little River basin.

Concern that the Piscataway were aiding and harboring fugitive Iroquois, who had robbed and reportedly killed settlers, led Nicholson, the new Virginia governor, to propose a meeting between the Indians and Stafford settlers.

In a March 1699 speech to the colony's legislature, Nicholson said his messengers to the Piscataway "Emperour" should "keep an exact Journal of their Journey" and "give a just and full account of their proceedings therein, and what in them lyes."

Nicholson especially wanted to know "how far they [the Piscataway] are of [from] the inhabitants? . . . if they have any ffort or ffortes? . . . what number of Cabbins & Indians there are, especially Bowmen? If any foreign Indians & what number of them? How the Indians subsist, be in point of provisions? . . . What trade they have & with whom?"

Nicholson also ordered the messengers to ask the Piscataway leader to come to Williamsburg, the Colonial capital, in May so he could speak to the governor and legislature. The Stafford County Court chose Harrison and Vandercastel, both justices of that court, as their emissaries.

Little mention survives of Vandercastel, the senior member of the expeditionary party. Union soldiers who occupied the Stafford courthouse during the Civil War destroyed most of the county's records.

We know that Vandercastel received a 420-acre grant from a Fairfax family on the navigable mouth of Little Hunting Creek, a mile from the Potomac River, in 1694. His name in the grant is spelled Vandegasteel. That holding, or another, was named Accotink. He and his wife, Martha, had a daughter, Priscilla.

After Vandercastel's death in 1701, Martha married John Waugh, a Stafford County sheriff and member of the House of Burgesses. Priscilla married a Mr. Hoy and was alive in 1753.

For information on Burr Harrison, we are largely indebted to John P. Alcock of Monterey, near Marshall. His 1991 book, "Five Generations of the Family of Burr Harrison of Virginia, 1650-1800," besides being an exemplary account of the family's early line, is an excellent study of Colonial life. Alcock's wife, Mariana, was a direct descendant of the first Burr Harrison, 1637-1697, the father of Burr Harrison, emissary to the Piscataway.

The first Burr Harrison's oldest son, Col. Thomas Harrison, would become the first justice and militia head of Prince William County in 1732, and his son, also Thomas Harrison, would hold those honors in Fauquier after the county's formation in 1759. Monterey, purchased by Thomas Harrison in 1765, has remained in the family.

Burr Harrison's second son, emissary Burr Harrison, ca. 1668-ca. 1715, was the junior member of the party that visited the Piscataway. His name, entered as "Bur Harison," appears after that of "Giles Vanderasteal" in the April 21, 1699, report of their findings to Nicholson.

Their report began with the Piscataway chief's refusal to visit the governor in Williamsburg: "After consultation of almost two oures, they told us [they] were very Bussey and could not possibly come or goe downe, butt if his Excellency would be pleased to come to him, and then his Exlly might speake whatt he hath to say to him, & if his Excellency could nott come himselfe, then to send sume of his great men, ffor he desired nothing butt peace."

The emissaries' account did not mention a translator. The Piscataway spoke an Algonquin tongue and probably English. Their account also did not speak of any accompanying servants, though it is difficult to believe two people would have ventured into uncharted wilderness alone.

Harrison and Vandercastel described the Indians' 300-plus-acre island in the Potomac River, known by 1746 as Conoy, for the Conoy or Kanawha Indians who had lived there previously. More recent maps name the island Heater's, for a 19th-century family that settled there.

At the west tip of the island, a few hundred yards east of the present Point of Rocks bridge, Harrison and Vandercastel described the Piscataway fort: 50 or 60 yards square with 18 cabins within the fort and nine outside the enclosure. About 40 years ago, the State of Maryland, which owns Conoy Island, took infrared aerial photographs of the island, which is now a nature preserve. The rotted logs of the fort and cabins remained visible as a dark red outline.

Harrison and Vandercastel noted that the fort and cabins housed about 215 Indians, 80 or 90 "bowmen," an equal number of women and about 46 children. "They have Corne, they have Enuf and to spare," the report said.

The adventurers saw "noe straing Indians, but the Emperor sayes that the Genekers [Senecas, or Iroquois] Liveswith them when they att home" in the spring and fall. In spring, the Iroquois migrated north to New York, and in the fall they left for the warmer Carolinas.

Harrison and Vandercastel also described their journey to the fort, which for Harrison began at the 3,000-acre family plantation on the north side of the Chopawamsic River, today the boundary between Prince William and Stafford counties. Only the Harrison-Tolsen family graveyard marks the location of the nearby house, its ruins bulldozed 40 years ago in the construction of Interstate 95.

The Harrison home was known as Fairview in the mid-1700s, but both Burr Harrisons and nearly all the 18th-century Virginia Harrisons who lived there are cited in records as from "Chopawamsic," the river and neighborhood name and the name of the local Anglican Church.

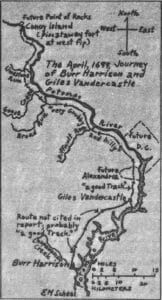

From Chopawamsic, Harrison journeyed 20 miles to meet Vandercastel at his Little Hunting Creek plantation, called the limit of "Inhabitance" in their journal. And from that point, on April 16, 1699, they "ffound a good Track ffor five miles," nearly to present-day Alexandria.

The journal continued, noting "all the rest of the daye's Jorney very Grubby and hilly, Except sum small patches, butt very well for horse, tho nott good for cartes, and butt one Runn of any danger in a ffrish [freshet], and then very bad."

Today this stream bears that warning and is called Difficult Run. It formed the boundary between Fairfax and Loudoun from 1757, when Loudoun was formed, until 1812, when the border shifted to its current location.

The night of April 16, Harrison and Vandercastel "lay att the sugar land," near today's Great Falls. By their reckoning, they had traveled 40 miles that day.

Setting their compass with the direction of the Potomac River -- northwest by north -- the party "generally kept about one mile ffrom the River, and about seven or Eight miles above the sugar land we came to a broad Branch," Broad Run today. "Itt took oure horses up to the Belleys, very good going in and out."

Six miles farther, they "came to another greate branch," Goose Creek. The party crossed that "strong streeme, making ffall with large stones" at the rapids by the future village of Elizabeth Mills, a little more than a mile from where the Goose meets the Potomac.

West of Goose Creek the expedition found "a small track" -- probably a deer or buffalo path -- until they came upon "a smaller Runn . . . Indefferent very," today's Limestone Run.

About "six or seven miles of the forte or Island," Harrison and Vandercastel described the landscape as "very Grubby, and greate stones standing Above the ground Like heavy cocks," meaning haycocks. These stones were the unusual formations of limestone conglomerate that, nearly a century later, formed the base and much of the interior of the U.S. Capitol.

The adventurers' description of the final three miles before reaching Conoy Island: "shorte Ridgges with small Runns."

In less than two days, Harrison and Vandercastel had traversed 70 miles, 65 of them through virgin forest, a remarkable feat of endurance.

After their pioneering expedition, other parties of explorers visited the peaceful Piscataway on Conoy Island, the last of record in 1712.

Roscoe Wenner, who lived by the island, and whose ancestors trapped beaver and game in that bygone era, told me many years ago that he "always heard the Indians died out from smallpox about 1715."

The era of the Indians of Loudoun and Fauquier ended in 1722, when the Iroquois agreed to migrate west of the Blue Ridge.