Ashburn Village's Agrarian Roots

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

As longtime area residents know, Ashburn was originally known as Farmwell, or Farmwell Station. That name dates back to at least 1802

According to one oft told local legend, the name Ashburn came when a bolt of lightning struck a tree — an ash tree — on a farm belonging to prominent citizen John Janney. The ash tree reportedly burned brightly and then continued to smolder for days afterward. This caused quite a stir and folks came from all over the area to check out the burning ash tree.

The first recorded use of the name Ashburn is around 1870 to describe Janney’s large farm, thus it was called Ashburn Farm.

Around 1895, former Nevada senator William Morris Stewart moved to the area and purchased Ashburn Farm. In 1896, the local post office became concerned about confusion between Farmwell and the similarly-named Farmville, a village in Prince Edward County. (It’s still there too — that’s where Longwood University is and it played host to the recent Vice-Presidential debate.) The push was on for new name and someone — possibly Senator Stewart himself — suggested Ashburn. And the rest is history.

by Charles Wadsworth from TheBurn 2016

Ashburn was originally called Farmwell (variant names include Old Farmwell and Farmwell Station) after a nearby mansion of that name owned by George Lee, great-grandson of Thomas Lee. The name Farmwell first appeared in George Lee's October 1802 will and was used to describe the 1,236 acre plantation he inherited from his father, Thomas Ludwell Lee II. George Lee, originator of the Farmwell name, died in 1805 and his property passed to son Doctor George Lee (1796-1858). Doctor Lee married Sarah Moore Henderson in 1827. Sarah is reputed to have given birth to 23 children, the eldest of which, George III, inherited Farmwell upon his father's death and granted a right of way across the plantation to the Alexandria, Loudoun & Hampshire Railroad (later the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad) in 1859. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The largest concentration of homes and businesses in eastern Loudoun County is the amorphous region of Ashburn Farm, Ashburn Village and Broadlands.

The post-1980s communities make up the county's most populous unincorporated area -- about 32,000 residents. (Incorporated Leesburg has a population of 36,000; unincorporated Sterling Park has 13,500.)

Yet just 20 years before the building boom, in the early 1960s, it was a thinly populated region. Within five miles of Ashburn Village were dozens of dairy farms of at least 100 acres each.

The 656-acre Farmwell plantation was owned by physician George Lee. It burned down in the mid-1980s.

The Ashburn area had its genesis in 11,182 acres granted to Tidewater speculator Thomas Lee from 1719 to 1728. Later, Leesburg would take his name, and he would become acting governor of Virginia. A century later, Lee's grandchildren and great-grandchildren owned and lived on the 4,700 acres that remained in the family.

By that time, there were four main divisions of Lee land: Coton (now Lansdowne), north of the future Route 7; Belmont, south of Route 7; Farmwell, east and south of Belmont; and the Forest Tract, west and south of Belmont.

The latter two parcels were owned by some of the most prominent Loudouners of the mid-1800s: politician and lawyer John Janney and physician George Lee and their wives, Alice Janney and Sarah "Sally" Lee. Each couple owned more than 600 acres and a large, rambling "summer house."

John Janney owned the Forest Tract, and sometime after the Civil War, its arable eastern section became known as Ashburn. Although the name means simply an ash grove or tree by a small brook, local residents claimed that a huge ash tree by the Janney home was struck by lightning and continued to burn for several days.

George Lee's plantation was named Farmwell, a name that first appeared in the 1802 will of his father.

As with other wealthy Loudouners, the Lees and Janneys spent winters in Leesburg, both on Cornwall Street.

Janney might have been Loudoun's most influential person of the mid-1800s. In 1840, when the Whig Party met in Richmond to nominate its favorite son for vice president, there were two nominees, Janney and John Tyler of Charles City County.

The vote was a tie, with Tidewater delegates voting for Tyler and upcountry delegates for Janney. The delegates voted again, and Tyler prevailed by one vote. After the convention, Janney revealed that, as was the custom for a gentleman, he had cast his ballot for Tyler.

When President William Henry Harrison died after a month in office, Tyler became the 10th U.S. president.

Janney was president of the 1861 secession convention that decided that Virginia should leave the Union. Janney opposed secession -- as did the other Loudoun delegate, John Armistead Carter of Crednal, near Upperville -- and he relinquished his commission upon handing a sword in its scabbard to Gen. Robert E. Lee.

After presenting the symbol of war to Lee, Janney paraphrased George Washington, who in his will admonished his nephews to draw the swords he willed to them only "in self-defense or in the defense of the rights and liberties" of the country.

Those who heard Janney's speech and saw his eyes fix on Lee wondered whether, in mentioning the defense of the country, Janney was referring to the United States or to the Confederate states.

Today, one looks in vain for anything named for Janney in the Ashburn area. His summer home, a large, T-shaped frame house with a ballroom, was named Ashburn. The dwelling, still in habitable condition, was bulldozed in 1987. Its site is in the middle of Ashburn Park.

Old-timers recall that dances, complete with a small orchestra (popular among Virginia Piedmont gentry a century or so ago), were held frequently at the Ashburn house after Nevada Sen. William Morris Stewart bought Ashburn plantation in 1895.

Stewart was known as the "Silver Senator" because he made a half-million dollars in 1856 defending claimants of the Comstock silver lode in Nevada. He was a strong proponent of silver, rather than gold, as the precious metal backing the paper currency.

Stewart turned Ashburn plantation into a large dairy operation and reportedly was the first dairyman in Loudoun to pasteurize milk through steam power. When colleagues and bigwigs came out from Washington, he would deck out his 40-man staff in white and treat guests to a farm tour. Stewart was especially proud of the steam-driven fans that kept flies away from the cow stalls.

As for the 656-acre Farmwell, it was divided among George and Sally Lee's 23 children -- four times the size of an average 19th-century family -- and innumerable grandchildren.

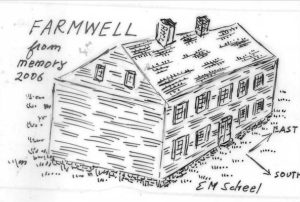

Farmwell was the largest 19th-century log house I have ever seen. Indian bird darts and arrowheads were imbedded in the chinking between the logs. Northwest of the house, a mineral spring (now a lake) had been a gathering place of Algonquian-speaking area tribes. Farmwell was unoccupied but solid when it burned in the mid-1980s. The edifice stood just northwest of Rising Sun Terrace and Cheltenham Circle.

Farmwell became the first area place name of note, being ascribed to a combined 1853 log church and school, its land donated by the Lees. They noted in the 1849 deed that their gift was to "aid the religious, moral, and intellectual improvement of the people residing in the vicinity." The site is near an unkempt graveyard and later schoolhouse near the northeast corner of Shellhorn and Ashburn roads.

As with Janney, no area place name today honors the Lees.

The village that grew up near the church (now called Ryan) was named Farmwell.

In January 1860, the Alexandria, Loudoun & Hampshire Railroad (now the W&OD Trail) established a depot at Ashburn Road. The post office there became Farmwell, and the original Farmwell became Old Farmwell.

It would be the farms' proximity to the railroad that would spawn the dairy industry. Farmwell Station was 45 minutes by train from Washington, and milk picked up in the early morning and shipped in ice-cooled cars could reach the big city without spoiling.

The post office might have kept the name Farmwell had it not been for the Farmville post office in Prince Edward County, established in 1800. In 1896, Stewart argued that the handwritten names were too similar, and so the name of the village was changed to match that of his farm, Ashburn.

As to how the Ashburn of today differed from the village of that era, I recently asked one of its senior residents, Elizabeth LeFevre Cooke. She mused, "The only noise we could hear in the morning were the Delco generators being turned on."

Copyright © Eugene Scheel