Time Stands Still at the Old Aldie Mill

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

Aldie Mill Historic Park![]()

Aldie Mill Historic District![]()

Aldie History![]()

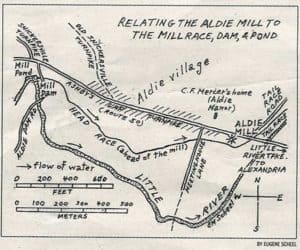

In June, 2006, the nearly 200-year-old Aldie Mill was turned over to the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority. The water-powered manufactory on Little River is one of only two working water-powered mills in the Virginia Piedmont open to the public; the other is Fairfax County's Colvin Run Mill.

The area where Little River flows through Bull Run Mountain was settled by James Mercer, and in 1764 he had a small mill built. Wherever a Mercer settled abroad, he named his domicile Aldie, after the family ancestral home in Perthshire, Scotland. Hence the name for the village, mill and manor house.

For 150 years, the fortunes of Aldie village were intertwined with the larger mill, which was completed in 1809. The mill ground wheat and corn not only from the lower Loudoun countryside but also from Fauquier and Prince William counties. The Virginia General Assembly chartered the village in 1810, and four of the hamlet's eight trustees were linked to the mill: Charles Fenton Mercer, who was elected to the assembly that year, provided the money for its construction; William Cooke was the contractor; Scotsman Matthew Adam was the millwright; and John Sinclair surveyed the property.

Cooke and Mercer, James Mercer's son, were the mill's joint owners. Their total shares in the mill were valued at $22,500 -- more than 10 times the assessed value of Mercer's Aldie home. They sometimes leased the mill for $2,000 a year -- six times a man's average annual wage at the time.

Within a decade, Aldie, at the nexus of three turnpike roads, became the fourth-largest community (268 people) in Loudoun County, after Leesburg, Waterford and Middleburg.

The village's rapid growth was tied not only to its location but also to the immensity of its mill, which boasted auxiliary operations for cutting timber, grinding land plaster and distilling fruit into whiskey. Five millstones imported from France allowed many customers to be served at a time. There was also an adjacent one-stone "country mill" for grinding feed for cattle and horses. Three water wheels set the apparatus into motion.

Virginia law decreed that when a millstone was vacant and operative, the mill could not turn away a customer. Many farmers relied on the mill for their livelihoods: Their refined produce drew high prices at the seaport of Alexandria, where it would be shipped to a needy Europe. Little River Turnpike (which, in Loudoun, became today's Route 50) ran a nearly straight-line course from the mill to Alexandria.

By the mill stands a store that sold staples brought by wagons returning from Alexandria. The store also sold refined grain, kept in a still-standing granary. The mill retained a share of the ground grain, known as a toll, usually one-sixth of the initially weighed corn and one-eighth of the wheat (wheat being denser than corn).

James Moore Douglass, the last Aldie miller, years ago told me a tolling tale that was passed down in his family, owners of the mill since 1835, when John Moore purchased it from Mercer:

"The miller asked the boy tolling the grain, 'Whose wheat is that?'"

" 'Mr. Fairfax's, sir.'

" 'Did you toll him?'

" 'Yes, sir.'

" 'Well, toll him again. He's a rich man and can afford it.'

"Next day the miller came upon the boy and asked:

" 'Whose cornmeal is that?'

" 'Mr. Jones's, sir.'

" 'Did you toll him?'

" 'Yes, sir.'

" 'Well, toll him again. He's a poor man; let's keep him poor.' "

Moore paid $10,000, quite the bargain, to Mercer, who had bought out Cooke. By 1835, the nation was in the midst of a financial depression, and Mercer, a U.S. congressman (1817-39) and no longer living in Aldie, had other interests.

Douglass told me he thought that the mill escaped being burnt by Federal raiders during the Civil War because Moore was a Union man and had voted against secession in 1861 -- one of five people in Aldie to do so. Douglass also mentioned that the mill was used by Confederates because its usual operator was Moore's son, Alexander, a staunch Rebel.

In late winter 1863, Union soldiers trying to elude capture dove into the wheat bins and buried themselves like rats. Others jumped into the hoppers and came near to being ground up in the flour. Col. John Singleton Mosby, commander of the Confederate raiders, wrote in his 1887 "War Reminiscences" that when his rangers pulled the Yankees out of the flour, "there was nothing blue about them."

After the war, when the largest corn and wheat farms were in the Midwest, mills there began using a roller process that produced a "whiter" flour by removing rodent excrement and other matter. The roller process also extracted the brown wheat germ from the kernel.

Whiteness was commonly equated with purity. So rather than going to the mill to buy brownish-colored wheat or flour, it became the fashion to go to the store and buy a five-cent loaf of white bread.

Observing this trend, Alexander Moore installed roller machinery at the mill and replaced the wooden water wheels and wooden mill dam with iron wheels and a stone dam. Douglass dated these renovations to 1877-81.

But the behemoths of baking -- the General Millses and Pillsburys -- won out, and about 1932, Aldie Mill stopped its flouring operations.

Cornmeal became the mill's staple, and Douglass said 1946 was his best year. Farms were expanding after World War II, and machinery makers hadn't yet converted from wartime uses to manufacturing portable grinding equipment for farm use.

The profit pendulum, however, swung back in 1955. The Mediterranean fruit fly got into the meal, and nearly half had to be returned to the mill. One water wheel stopped grinding. Federal health officials castigated Douglass because his cornmeal contained too much rodent excrement. Douglass tried in vain to explain that the impurity was in the corn before it was brought to the mill.

About 1964, the second wheel gave out. The Fitz Water Wheel Co. told Douglass it would cost $10,000 to replace them, so it became cheaper for a tractor to run the machinery, albeit on a smaller scale. In 1971, Aldie Mill turned out its last bag of cornmeal. It was the last of the 18 water-powered mills then standing in Loudoun and Fauquier to close; in the early 1800s, there were more than 140 in both counties.

When I interviewed Douglass in the mill office in 1977, he reminisced by leafing through a worn ledger. He stopped at the page where the mill had loaned $5 to former President James Monroe -- it was not repaid. He showed me a 1920 clipping about the mill's one casualty: Lucien Carter was mangled in the machinery while trying to fix it. Douglass pointed to the safe. Robbers had tried to bore through its lock. Close, but no cigar. He looked at me and said, "Mills were built to shake from the noise, and when the noise stops, they collapse from the stillness."

Douglass and his wife, Sarah Love Douglass, did not let this happen. In 1981 they donated the mill property to the Virginia Outdoors Foundation. For 19 years restoration work proceeded, supervised by an English millwright, Derek Ogden, and financed in part by an anonymous $2 million gift.

The problems today are those of yesterday: either no rain or too much. Meanwhile, two indefatigable beavers are damming the millrace, blocking the flow of water to the mill wheels.

Copyright © Eugene Scheel