Timeline of Important Events in African American History in Loudoun County, Virginia

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker

and the Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg , Virginia

Note: New entries from The History of the County Courthouse and Its Role in the Path to Freedom, Justice and Racial Equality in Loudoun County, Report of the Loudoun County Heritage Commission 2019 have been added to this timeline.

See also the Loudoun History timeline on this site, the African American history and education resources of Loudoun at the Friends of the Balch Library web site, and the Edwin Washington Project : Documenting Segregated Schools of Loudoun County.

A Chronological View of Events:

1709-1720s: The initial settlers populate their grants of land with slaves and white overseers. One overseer superintends fewer than a dozen slaves. After clearing land they plant corn, wheat, and tobacco, the main crops in colonial times.

Early 1730s: Slaves comprise more than half of the early settlers, as absentee landlords settle them in “Negro Quarters” run by a white overseer.

October 1742: John Colvill’s “Negro Quarter” near the mouth of Quarter Branch and the Potomac is the first mention in print of a slave population.

1749: An Anglican minister, the Reverend Charles Green’s census of lands to become Loudoun records about 400 “ Negros,”about 22 percent of a total population of some 1,800. Absentee landlords, all from Stafford and Westmoreland counties, own about 70 percent of the slaves. Thomas Lee, Governor of Virginia, leads the list with 61 slaves. Among resident landowners, Elisha Hall, a Quaker, owns the most slaves, 10.

1749: Reverend Green notes that “The County born Negros are chiefly Baptised.” Does this Christian heritage stem from trying to please, copying another’s tradition, promise of eternal life, or the biblical tradition of racial equality?

1757: At Loudoun’s formation there are about 550 slaves, 16 percent of a total population of about 3,500. Absentee landlords own about 65 percent of the slaves.

1764: For the first time a census lists patrollers to “visit all negroe quarters and other places suspected of entertaining unlawful assemblies of slaves or any others strolling about without a pass.”

1764: At the close of the French and Indian War there are about 1,100 slaves, or 19 percent of 5,800 persons. Now, about 60 percent of the slaves are owned by residents; 40 percent by absentee landlords.

1768: Three slaves of George West, the county surveyor, strike overseer Dennis Dallas with axes and hoes “so he instantly expired.” The slaves are hanged, March 2, in the county’s first public execution. “Mercer” hung and dismembered (quartered) following murder conviction.

1773: On the eve of the American Revolution, the population is 11,000, among them 1,950 slaves—17 ½ percent of the populace, the norm for colonial Loudoun. The average cost of a slave is about $125—about a third of what an average man earns in a year.

1774 – Loudoun Resolves adopted. Population estimated at 11,000 including 1,950 enslaved

1775-1783: Revolutionary War

1776: Declaration of Independence read from Courthouse steps.

1778:Virginia bans importation of enslaved people.

April 1778: Jane Robinson of eastern Loudoun, a mulatto born to a white woman, is the first to receive emancipation under 1765 Commonwealth legislation.

1782:Virginia law makes it possible for county courts to grant manumission to the enslaved, leading over time to a large growth in the free black population.

1790: The first U. S. census lists 18,962 persons; 4,213 are slaves, or 22 percent of the total population.

1800: Loudoun registers its largest slave population, 6,078, or 28 percent of a total 20,523 persons. Freed by various state laws, 1785-1792, there are 333 free Negroes, or 1.54 percent of the population.

1800-1830: Quakers and Methodists, the latter eschewing the national church’s neutral position, lead the spiritual crusade against slavery. Leesburg’s Methodist Church and Lincoln’s Goose Creek Meeting host many anti-slavery discussions.

1804:The Literary Magazine prints a byline from Leesburg: “a Negro quarter of Col. T. L. [ Thomas Ludwell] Lee, near Goose Creek, was struck by lightning, and two negroes were struck dead, and six or seven wounded; one of the wounded soon died and it is hoped the others are out of danger. They had assembled for the laudable purpose of prayer, and were singing hymns at the period of this awful visitation.”

1806:Virginia General Assembly decrees that any African American person emancipated after May 1806 has 12 months to leave Virginia or face re-enslavement.

1808:U.S. ends importation of enslaved people.

1812-1815: War of 1812

1816: American Colonization Chapter established in Loudoun, with strong support from prominent citizens including Charles Fenton Mercer and President James Monroe (1817-1825).

December 1817: Eleven months after organization of the American Colonization Society, its goal to free slaves and transport them to Liberia, Ludwell Lee of Belmont, and the Reverend John Mines of Leesburg Presbyterian Church, start a Loudoun chapter of some 70 men. Seven years later, Quakers organize the Loudoun Manumission an Emigration Society, which also stresses "exposing the evils of African slavery." By the 1830s, this purpose dominates the movement" for most freed blacks were born in America and cannot adjust to Africa.

1818: A letter from “Judex” (a court arbitrator) in Leesburg’s Genius of Liberty, warns that teaching slaves to read and write is illegal. “Negroes, teachers and justices look to it: the order of society must prevail over the notions of individuals.”

1820: Loudoun registers its largest pre-Civil War population, 22,072. Slaves number 5,729, about 25 percent, free Negroes 829, or about 3.7 percent. Of 140 black households, 19, or 13.6 percent, own slaves. The decline in the number of slaves in Loudoun County, because of moral concerns and a large Quaker population, counters the national trend - a 65 percent increase since 1800.

By 1820: Slave boys sell at $100—$150; single females at $300, females with a child at $400—$500. Male slaves generally sell for more than females. Skilled laborers and the young are in demand.

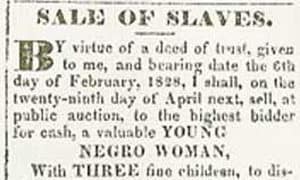

1830 advertisement for slave sale

1820s: In the first instance of school desegregation, John Jay Janney in his 1901 memoirs asserts that blacks living on Quaker farms attended school with whites in the log schoolhouse in Purcellville (once at Bethany Circle), and the Goose Creek Friends’ Schoolhouse at today’s Lincoln.

1821: Newspapers often show sympathy for slaves. In September the Genius of Liberty notes “a drove of negroes of about one hundred unhappy wretches” passing through Leesburg on a Sunday to “a southern destination.”

1824: Quakers organize a Loudoun Manumission and Emigration Society (LM&ES) at the Goose Creek Friends’ Schoolhouse. The group stresses “exposing the evils of African Slavery.”

November 1825: The LM&ES, in an invective tirade in the Genius of Liberty, calls slavery “such an atrocious debasement of human nature as to demand immediate extinction.”

1827: The LM&ES hosts the first statewide convention for the abolition of slavery and urges the new 1825 Virginia Constitution to include a plan for gradual emancipation. The Goose Creek Friends’ Meetinghouse hosts the convention.

The LM&ES and Loudoun Colonization Society chapter send their first emigrants from Norfolk, Virginia on the brig, Liberia, to Liberia.

1828:Quaker Yardley Taylor convicted and fined for helping an enslaved man try to escape. Loudoun population 21,936 total, including 5,363 enslaved and 1,029 free blacks.

1828-1831: There are a sizeable number of runaway slaves. Edward Hammett, Loudoun’s jailer, records 14 runaways in jail and 42 slaves in jail to be returned to owners.

August, 1829: The RichmondWhig notes: “Died at his residence in Loudoun County, a few days since, Tommy Tomson, a black man, aged 130 years. “He retained his mental and physical facilities, to a few days previous to his disease.”

1830: Mr. Heaton’s one surviving letter to the Lucases reads: “You have felt and witnessed the degradation of your colour in this country. But you will have gone to a country where the Noblest feeling of Liberty will spring up. The prize I mean is the prize of Liberty.” Sixty-five percent of the 5,343 slaves, 23.8 percent of 22, 796 persons—a prewar high—are under 24 years. Of the 1,079 free Negroes, 4.7 percent of the population (nine families), or 1 percent own slaves.

1831: Loudoun has 75 schools for 900 poor children, and they are open for only 70 days. In 1846, Virginia passes a bill giving counties the option of establishing public schools if two-thirds of the voters agree. Six counties, including Culpeper, vote for public education. The others, Loudoun included, reject it, fearing that the schools would admit free blacks.

1829-1836: Farmer Albert Heaton of Woodgrove, a member of the Colonization Society, receives six letters from his emancipated slaves in Liberia. Mars and Jessie Lucas complain of the country’s primitive state and the Africans’ ignorance of Christianity.

1831: In late weeks of the year, following Nat Turner’s slave revolt in Southampton County, Virginia, patrols again set out. They check slaves for passes and free blacks for identification papers. “Run Negro, run, or the Pa-trr-oll will get you,” blacks told their naughty children—well into the postwar years.

December 1831: Loudouners petition the state legislature to gradually emancipate slaves. Five petitioners own some 120 slaves. The legislature does not act.

1831:Large-scale sales and subsequent movement of enslaved people out of Loudoun begin in response to growing cotton production in Deep South; continue until Civil War.

1831-1832: The insurrection prompts the Virginia legislature to pass acts forbidding slaves and free Negroes to assemble for the purpose of reading, writing, or listening to a black preacher. However, slaves of one master can meet for prayer.

1832: The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal is complete along the Potomac River opposite Loudoun County. The canal’s completion makes possible the shipment of slaves from Washington and Alexandria to the large slave warehouses at the Monocacy River’s mouth and at Licksville, Maryland. Via Noland’s and Spinks’ Ferries they are shipped to Loudoun and southward.

Mid-1830s-1839: Free black Leonard Grimes, a carriage driver, conducts several slaves to safety, including seven in one barouche. This last daring escape, along the Leesburg Pike, leads to his arrest, trial, and two-year prison sentence—the minimum penalty, due to his “former good character.”

1836: Richard Henderson, first Commonwealth’s Attorney, contends it is virtually impossible to prosecute free blacks who have come to Loudoun to work from other states, which had been illegal since 1793. Henderson contends that for every person prosecuted by the county court there are seven to eight extensions.

Mr. Henderson petitions the state legislature to remove all free blacks to “the Western coast of Africa,” remarking that those from out of state live in a condition of “poverty, vagrancy, and crime.” His petition is rejected.

1836-1846: Margaret Mercer uses proceeds from the sale of family lands and from her girls’ school at Belmont to emancipate her family’s slaves and send them to Liberia.

By 1840: The low ridge east of Catoctin Mountain is known as Negro Mountain because of slaves and free Negroes living there. It is the first geographical feature to have a name specifically associated with race.

1840: Free Negroes comprise 6.45 percent, of 1,318 persons of a population of 20,431. Slaves comprise 25.8 percent of 5,273 persons.

1840: Trial of Leonard Grimes for aiding enslaved people to escape results in light sentence.

1843: Liberia’s census records that only four of the thirty emigrants from Loudoun in 1827 remain in that country. Two had returned to the U.S., one to the Waterford in Loudoun County. Four had gone to Cape Palmas or Tiembo, in other areas of Africa. Twenty-four had died of “African fever,” many in their first year of arrival.

1844: Slaves John W. Jones and his half-brother, George Jones, escape to Elmira, New York, and through the early 1860s assist some 800 slaves to escape to Canada.

Samuel M. Janney, of Springwood, near Lincoln, writes a series of anti-slavery letters in the AlexandriaGazette. He proposes an end to domestic slave trade and argues for the “superiority of free labor.”

December 1844: In a letter to a friend, Samuel Janney writes: “I think public sentiment advancing here in favor of emancipation. There are many more opposed to slavery than is generally supposed, but they are afraid to avow their sentiments.”

1845: Samuel Janney’s memoirs, published in 1881, provide evidence of a pre-Civil War Underground Railway through Loudoun. In the memoir he writes of visiting Pennsylvania before the war and meeting a “considerable number of blacks” he knows.

1845: The two largest Methodist congregations in Loudoun divide over slavery. In Leesburg, the Northern Methodists, opposed to slavery, move out of the congregation's 1785 church to a church on Liberty Street, where blacks hold services in the late 1850s. (The building, almost forgotten, stands today.) In Middleburg, the breakaway pro-slavery Methodists leave that congregation's 1829 Asbury Church and move to the present 1857 church. Blacks worship at Asbury during the Civil War.

1846: Trial of Nelson Talbot Gant for stealing his enslaved wife results in dismissal of charges.

February 1846: Virginia passes a bill giving voters the option to establish public schools. Six counties (including close-by Culpeper) vote for public education. The others, including Loudoun, fear that the schools will be open to free blacks, who for decades have been taking jobs away from whites.

1849: Samuel M. Janney persuades Thomas C. Connolly, editor of The Loudoun Chronicle, to start a newspaper promoting public education and emancipation of slaves. But they lack funds, and there are already four local newspapers.

A Grand Jury accuses Samuel Janney of a “calculated” effort to “incite persons of color to make insurrection or rebellion” and of saying that slave owners “had no right of property in their slaves.” He is tried in June 1850, but is acquitted on both counts.

1840s-1850s: William Benton, builder of Oak Hill, Woodburn, and many other prominent Loudoun homes, defies state law by teaching his slaves (he owned 19 in 1850) to read and write. Possible addition here: Eight Waterford black men and women listed in 1850 census as being literate . BCSouders

1850: Samuel Janney tried in Courthouse for “inciting slaves to revolt” in his letters to editor criticizing slavery; acquitted on grounds of First Amendment right to free speech.

1850: At mid-century persons owning the most slaves: Elizabeth Carter (widow of George Carter) of Oatlands, 85; Lewis Berkeley of Aldie, 58; John P. Dulany of Welbourne, 52; John A. Carter of Crednal, 32; Townsend McVeigh of Valley View, 31; Humphrey Brooke Powell, of The Shades, 27. All except Mrs. Carter live in the Aldie-to-Upperville corridor.

Of a population of 22,679, 5,641 or 24.1 percent are slaves; 1,357 or 5.6 percent are free Negroes. Loudoun registers its largest pre-war black population.

A free black man’s pay was, in one case, $120 per year and included “room and board,” which could cover cutting rights to firewood, cornmeal, flour, bacon, a bit of garden ground, and space to live.

Samuel Thompson, who lives near Telegraph Springs, is the wealthiest of free blacks with $4,500 worth of real property (equivalent to $370,000 today). He owns no slaves. The average free black owns $473 of real property (about $33,000 today).

1852: Joseph Trammell issued “Freedom Paper”.

1856: Benjamin Drew’s book, The Refugee, presents the first interviews with escaped slaves George Johnson, who lived near Harper’s Ferry, and Peyton Lucas, of Leesburg. They describe conditions, whippings, other degradations, and escape.

1857: A broadside about Yardley Taylor, Quaker map-maker, orchardist, and U.S. mail carrier, accuses him of assisting slaves in Loudoun and Fauquier to escape, and of being “Chief of the Abolition clan in Loudoun.”

1857:U.S. Supreme Court in Dred Scott case says enslaved people were not and never could be citizens.

By 1858: Prices for slaves have increased nearly ten times since 1820. A skilled male laborer might bring $1,600; an unskilled worker, $1,200. A young woman can be sold for $1,000, and if she has light skin, much more. By 1860, prices decrease.

1859: Daniel Dangerfield, a slave helper at Aldie Mill, escaped in 1853 and is arrested in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. Sentiment is strong in Loudoun for his return, but Pennsylvania refuses to extradite.

October 1859: Following John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, fifty Hillsboro militiamen, ages 15 to 75, trek to the Ferry to “protect Loudoun.” Free blacks stay clear of the militia and avoid whites in authority.

November 1859: Rumors of impending conflict between the North and the South prompt three civil guard units to monitor the Potomac crossings and scout areas around Short Hill and in the Blue Ridge. In December, Leesburg hosts a military fair. Tensions created by these rumors, and eventually the outbreak of war, keep free blacks on edge until the war ends in 1865.

Tennessean John Bell, owner of many slaves and advocate of keeping the status quo, wins Loudoun’s presidential election, 2,033 to 778. The anti-slavery candidate Abraham Lincoln garners 11 votes, all in the Purcellville South Precinct (the area about today’s Lincoln). Stephen Douglas, perceived to be anti-slave, gets 120 votes.

1860: On the eve of war, 5,501 or 25 percent of 21,774 persons are slaves; 1,202 or 5.7 percent are free blacks. Of those free, 51 percent are mulattos. Of 166 free black households, 7 or 4.2 percent, own slaves. See 34 Largest Slaveholders; Slave Ownership.

Twenty percent of free blacks own real estate, their property averaging $317, a decline of a third since 1850. By contrast, the average farm is worth $8,700, an increase of 15 percent since 1850.

Slaves are hired out, a practice for a generation, with the annual rate about $120 (a third of a white laborer’s annual wage). Slave women are rented for $50 to $60 a year. In the Waterford area a slave contract could include $85 per year for a man in 1853 plus clothing: “one winter coat, one pair field pants, one vest, two pair summer pants, four shirts, two pair socks, two pr drawers one pair work boots one pr good summer shoes one hat and pay his taxes.”

ca. 1860-1865: Margaret Harrison Benton of New Lisbon (now Huntlands) instructs her slaves in reading and writing, and after the 1862 Emancipation Proclamation, in an occupational trade.

ca. 1861-1865: Possibly 50 slaves or so serve in the Union Army, officially or as helpers in such tasks as horse handling, mess duty, cutting hair, carrying materiel, and other items. Perhaps twice that number serve the Confederate cause in similar jobs. Most of the slaves who served (freedmen after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863) remain anonymous.

At least four Waterford men: James Lewis, 55th Massachusetts; Henson Young, 1st US Colored Troops; Webb Minor of the Loudoun Rangers, and Ed Collins, thought to be a Loudoun Ranger are known to have served. Lewis may have been a freed slave and Collins was free at the time of his enlistment. While Minor was born free, Young was a slave of William Russell Sr .

April 1862: Diarist Catherine Broun of Middleburg writes on April 30: “Servants are running off. Poor things, they think they are going to their friends. How disappointed they will be, but we want them to go and try them.”

May 1862: Mrs. Broun writes: “Servants are all free now. Several [ Union] regiments from Maryland laid down their arms and went home. Said they thought they were fighting for the Union, but as it is for the Negroes they would fight no longer.”

September 1862: Mrs. Broun makes note of an “ African Church,” the first indication blacks are worshipping at Asbury Methodist Church, Middleburg, and the earliest reference from that period to a separate church for blacks. A 1976 reference sites blacks as worshipping separately at the Northern Methodist Church on Liberty Street in Leesburg during the early 1860s, and perhaps even before the war began.

1864-1865: Loudoun’s John W. Jones (see article) interred some 2,950 Confederates who died at Elmira, New York’s Camp Chemung prisoner-of-war camp. Jones also documented the names, dates, and other known facts about the interred

1865: 13th Amendment to Constitution abolishes slavery; Congress creates Freedmen’s Bureaus to give food, clothing and fuel to Freedmen.

1865: The two churches where blacks worshipped during the war shortly become Mount Zion Methodist, Leesburg, and Asbury Methodist, Middleburg, the latter continuing under its 1829 name.

March 1865: The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, better known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, establishes headquarters in Leesburg and Middleburg. The Bureau’s job is to educate and protect freed blacks, and to help them adjust to a free society.

May 1865: Mrs. Broun: “See the colored people going about with their school books. Yanks teaching them.”*****

Late 1865 or January 1866: Leesburg blacks establish a “Colored Man’s Aid Society” to assist their infirm and indigent. Lauding the enterprise, the Democratic Mirror editorializes: “The negroes of this community are, as a general thing, polite and well behaved.” See article.

Late 1865 or January 1866: The Freedman’s Bureau establishes a school at Middleburg, and one across the road from present Asbury Methodist Church, near Hillsboro.

1866:First Civil Rights Act guarantees equal rights in the courts, property, and contracts, but not the vote.

1866: Freedman’s Bureau established in Loudoun; first public elementary schools for African American children built in Lincoln (Janney’s School) (1866) and Waterford (1867), with help from Quakers, Baptists, and Freedmen’s Bureau. In 1867, Carolyn Thomas, Quaker, teaches at Freedmen’s Bureau school in Leesburg; also the instructor for Edwin Washington. There are two schools in Leesburg: “the African School,” probably at the Northern Methodist Church, and Bailey’s School, on South King Street.

The first known local black teacher is the Reverend William L. Robey, at Leesburg’s African School. The Washingtonian on June 22, 1866 states: “ William Robey has for more than a year past been teaching a large number of freed boys and girls, and I think with considerable success.”See William O. Robey; article*********

July 1866: Black trustees for “the Colored people of Waterford and vicinity” buy the first land for a school for blacks in Waterford.

1867: With financial help from the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Philadelphia Friends the Waterford School is built, to be used “as a school house for colored children and for church purposes.” Its ninety-year tenure is the longest for any school for African-Americans. See Second Street School.

The first postwar churches for blacks organize: Mount Zion Methodist at Leesburg, led by the Reverend William L. Robey; Shiloh Baptist at Middleburg, founded by the Reverend Leland Warring, and Trinity Methodist Church at Rock Hill, near Lincoln.

1867-1868: Snickersville physician George Emory Plaster, former Confederate Army lieutenant, represents Loudoun County at the Richmond Underwood Convention, which gives blacks the right to vote, provides for statewide public education, and leads to Virginia’s readmission to the Union in 1870.

1867-1870: Reconstruction Acts impose Army rule on South, including First Military District in Virginia. Military-appointed Governors, Republicans and Unionists control state government.

ca. 1867: Asbury Methodist Church for blacks, near Hillsboro, organizes with the first services held “somewhere on the mountain [Short Hill],” then later at the Freedmen’s Bureau School. Nathaniel M. Carroll is the first pastor.

1868: The Freedmen’s Bureau builds a school for $150 “to be used for the education of the colored youth of Willisville and for church purposes on Sabbath Day.” This first public school for blacks in southwest Loudoun is complete the next year. The church’s successor becomes Willisville Methodist Chapel.

October 10, 1868: the Reverend Robert Woodson of Alexandria founds eastern Loudoun’s first Negro church, Oak Grove Baptist, then called Woodson Mission.

1868: 14th Amendment enshrines civil rights for all U.S. citizens, including “due process” and “equal protection” under the law. Freedmen’s Bureau closes Loudoun offices.

By March, 1869: Seven schools educate black children: near Hillsboro, at Leesburg, Lincoln, Middleburg, Waterford, Willisville, and a new school called Harmony, either at Hamilton or at nearby Brownsville.

By 1869: Under Freedmen’s Bureau wage guidelines, black field hands receive $12 to $15 a month plus board, clothes, and medical attention. Women field hands receive $5 to $8 a month with board: women cooks and house servants, $6 to $10 with board; $14 to $18 without. These wages are equivalent to those paid white labor.

1870: The first census taken after all blacks are free lists 5,691 “colored,” 27 percent of a population of 20,929. Many blacks had left Loudoun for jobs in Alexandria, Baltimore, and Washington.

With Virginia again achieving statehood—a prerequisite was establishment of a segregated public school system—the Freedmen’s Bureau offices close. The Freedmen’s Bureau schools of the 1860s become public schools for black children.

1870: 15th Amendment ratified, guaranteeing the right to vote.

1870: Virginia re-enters Union, civilian government restored.

1870-1871: Enforcement Acts (including Ku Klux Klan Act) passed by Congress to suppress white violence against Freedmen, protect right of blacks to vote. President Grant sends federal troops to crush KKK in South Carolina.

ca. 1870-1920s: Typical of whites’ descriptions of esteemed blacks in newspapers, this obituary notice of 1887: “.. ‘tis true he was of the colored race, but his life was actuated by principles as white and as pure as any man’s.” Newspaper articles often address blacks as “Aunt” and “Uncle” rather than “Mr.” or “Mrs.”

1872: Loudoun County’s first school superintendent, Donald Wildman, writes in his yearly report to the state that blacks “are much more liberal in their proportion to their means than the whites, and are willing to submit sacrifices to accomplish their object.”

The Rock Hill Methodist Church (known as Austin’s Grove since 1911), organizes under the leadership of the Reverend Henry Carroll. It meets at the Rock Hill School for blacks.

1873: V. Cook Nickens, a Leesburg barber, is the first elected black official, serving for a year as a constable of Leesburg Magisterial District.

1873: Democrats capture Virginia statehouse (governorship and legislature).

1873: U.S. Supreme Court rules that states, not federal government, have power to enforce civil rights guaranteed under 14th Amendment.

September 1873: The first known black fraternal grouping, Middleburg’s Aberdeen Odd Fellow’s Lodge, organizes. For nearly fifty years one of its main objectives is to celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation of September 22, 1862. Negro fraternal organizations and their ladies’ counterparts begin to wane by the late 1930s and disappear by 1980.

1875: Providence Primitive Baptist Church, on Church Street, Leesburg, organizes, led by the Reverend Harvey Johnson; its 1875 building, the first postwar Negro church to arise that is still standing, is complete by June.

The Virginia Marble Company begins full-scale mining operation at the old Mount’s Marble quarry by Goose Creek. At about the same time the Leesburg lime quarries are intensively mined. Through the 1920s these quarries are the largest employers of blacks, each employing from 30 to 50 workers.

1875:Second Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination in public places, transport, and jury selection (but not schools), yet at same time, U.S. Supreme Court sharply curtails ability of federal government to stop mob violence against blacks in the South.

1875-1908: The following towns draw their corporate limits to exclude Negro sections: Hamilton (1875), Lovettsville (1876), Hillsboro (1880), Round Hill (1900), and Purcellville (1908). The Hamilton, Hillsboro, and Round Hill corporate limits still reflect those exclusions.

1876: Leesburg’s Mirror mentions a Negro political group named “The Invincible Republican Club of Leesburg, Virginia.” They are indebted to the Republican Party for their “freedom and rights.”

1877: The first land and public building bought for Negroes in Mercer District is the still-standing St. Louis School.

1877: End of Reconstruction; all former Confederate states now under Democratic rule; withdrawal of federal troops from Virginia.

1878: A deed notes that the first Snickersville (now Bluemont) public school for blacks is open on land “upon which is now a house used as a free school for education of colored people, and also used as a place of public worship by said colored people.” The First Baptist Church of Bluemont organizes here in 1888.

Dr. Benjamin Franklin Young is noted on the deed to the Snickersville School. This first known black physician, apprenticed under Dr. George E. Plaster, ca.1870, former lieutenant in the Confederate Army and Snickersville physician.

1880: Lynching of Page Wallace, an African American accused of raping a white woman, at McKimmey’s Landing at Furnace Mountain. He had earlier escaped from the Loudoun County jail in Leesburg.

1880: As the need for farm labor increases and jobs in the cities decrease, blacks move back to the country. They now comprise 31 percent or 7,243 persons of a total population of 23,634. This number will not be surpassed until the mid-1990s.

By 1880: Sixteen of the eventual 27 main black villages and hamlets have formed: Bowmantown (“Down in the Flats”), Britain (Guinea or New Britain), Brownsville (Swampoodle), Gleedsville, Guinea Bridge, Howardsville, Macsville, Marble Quarry, Oak Grove, Rock Hill (Middletown or Midway), Rock Hill near Lincoln, Scattersville (Mt. Pleasant), Stewartown (“Up in the Hollow”), Watson (Negro Mountain), Willisville, and an unnamed village along Snickers’ or Butcher’s Branch near Snickersville. The lots are generally on poor and wooded land.

1881: The Reverend Nathaniel Carroll organizes Hamilton’s Mount Zion African Methodist Church. Its congregation is at first served by circuit riding preachers. The present church building dates from 1928.

1882: A Middleburg school for blacks replaces the Freedman’s Bureau school, and is the only school to be named (unofficially) for a Loudoun black leader—principal Oliver L. Grant.

1883 –Mass meeting of African American leaders petitions Courthouse to protest lack of rights.

1883: U.S. Supreme Court strikes down main provisions of 1875 Civil Rights Act.

1884: The first large school (four rooms) for blacks opens on Union Street, Leesburg. All black schools are officially designated by letters until 1919; white schools are identified by numbers. This school, still standing, is “A,” in Leesburg District.

1884-1885: Among several black congregations building churches in the 1880s are two in Lincoln, made of stone—forerunners of later Negro stone churches in Rock Hill and Willisville. The Lincoln churches are Mount Olivet Baptist (1884) and Grace Methodist (1885).

1885: Second School superintendent William Giddings, a former Confederate colonel, writes of only “faint murmurings of opposition” to blacks receiving a free education. “This new era, in compensation for the sufferings and losses of our people, has brought many blessings, the greatest of which is our public school system.”

1886: A new Hillsboro-area school for blacks is established. It still stands.

1887-1888: William H. Ash, born a Loudoun slave, is elected to the House of Delegates, representing Amelia and Nottoway Counties. He was one of 87 Negroes elected to the General Assembly, 1867-1895; none represented Loudoun or adjacent counties. Mr. Ash, a Hampton Institute graduate and agriculture teacher, returned to Loudoun in the 1890s and taught at the Leesburg School.

1888: Verdie Robinson moves his barbering trade from Baltimore to Leesburg. It’s a whites-only trade; the barbers cut blacks’ hair at their homes for half the price. Robinson’s, now on Loudoun Street, is the county’s oldest operating black business.

A new Hamilton-area public school for blacks, still standing in Brownsville, is established.

October? 1889: The first Round Hill public school for blacks opens north of town on the Woodgrove Road.

Early November 1889: Orion Anderson, accused of accosting a white woman, is taken from the Leesburg Jail and lynched—the first of record in the county.

1889: Lynching of Orion (sometimes Owen) Anderson at quarry near Leesburg railroad station for scaring a white girl. A mob broke into the Leesburg jail, overpowered the sheriff and deputy, and dragged Anderson down Church Street before hanging him from a quarry derrick—the first of record in the county.

November 15, 1889: Democrat Philip W. McKimmey defeats Republican William Mahone in the election for governor, 2,835 to 1,431. Return of the old-line political regime leads blacks to suspect that segregation in its many guises will return shortly.

December 9, 1889: For the first time a county newspaper, Hamilton’s Republican Loudoun Telephone, describes a Negro village without ever mentioning race: “ St. Louis. Here you will find as good, whole-souled and hospitable people as ever lived . . ..”

1890: Hamilton and Purcellville area blacks organize the yet-to-be-named Loudoun County Emancipation Association. It meets that summer at Fayette G. Welsh’s farm west of Hamilton. Meetings are held there and at various area farms through 1909. Also see Howard W. Clark Sr.

ca. 1890: Jim Jackson’s store at Oak Grove opens for business; it closes in 1930—the longest-running black business in eastern Loudoun.

1891: The Loudoun Telephone editorializes: “ Virginia cannot afford to have the Jim Crow car stand among her products at the [ Chicago] World’s Fair [of 1893].”

1893: George William Lee, a black man, opens his Purcellville barbershop and continues cutting hair for whites only until retiring in 1950.

1896:U.S. Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson legitimizes “separate but equal” doctrine.

1898: The St. Louis Colored Colt Show is chartered “to hold exhibitions of horses and colts and to manage and conduct contests of speed and jumping; and other such tests. But no gambling of any sort shall be allowed.” These events continued into the 1930s.

1900: A slow decline of blacks to total population begins. They now comprise 27 percent of 5,868 or 21,948 persons. Their number of registered voters is 1,046 to 17.8 percent to the whites’ 3,874 or 24 percent.

The Washington & Old Dominion Railroad’s Bluemont Line ( Alexandria to Bluemont) segregates its passenger cars in accord with the new state law. Blacks sit in the rear of the car.

1902:New Virginia Constitution restricts voting rights of blacks and poor whites while adding the requirement for segregated schools in the state’s organic law.

1902: A new Virginia Constitution inaugurates the literacy test and a poll tax of $1.50 (more than most blacks’ daily wage). Voters for president decline from 4,800 in 1899 to 2,072 in 1903. The decline in Negro voters is not known.

August 1902: During August Court Days, an annual festival occurring during the time of major trials at the Courthouse, a group of inebriated whites storm the Leesburg Jail, and lynches Charles Craven. He had allegedly killed a juror who helped convict him of burning a barn. An inquest determines no one saw the lynchers. The tragedy ends the tradition of August Court Days for many years. The defendants, all from Loudoun County, are acquitted. See Mirror articles; Rust Diary enteries.

1908: Confederate Soldier statue unveiled at Courthouse.

December 1909: The Loudoun County Emancipation Association incorporates “To establish a bond of union among persons of the Negro race, to provide for the celebration of the 22 nd day of September as Emancipation Day, or the Day of Freedom, to cultivate good fellowship, to work for the betterment of the race, educationally, morally, and materially.” See Loudoun County Emancipation Association.

January 1910: The Emancipation Association buys ten acres, soon to be known as the Emancipation Grounds, just south of Purcellville. In August it meets there under a tent.

1913: Charlie Willis, with a loan from Harris Levy, prior white storekeeper, opens his store at the village of Levy, southwest of Aldie. It remains remained open until 1974—a Loudoun record under one person’s ownership.

1914-1918: World War I (U.S. enters war in 1917).

1914: Round Hill’s Arch Simpson designs and superintends the building of the Emancipation Grounds’ Tabernacle, patterned after the whites’ Bush Meeting Tabernacle. It holds 1,200, and admission to the September Emancipation Day event is 25 cents.

1917: A group of black men organizes The Willing Workers’ Club at Purcellville, and under trustees William M. Johnson, George W. Lee, and Lewis S. Rector, buys land for a school for black children.

Charles Ashe witnesses a third Leesburg lynching, from a tree on the grounds of old Leesburg High School (for whites). Ashe remembers the victim “crying and hollering—tell my mother I didn’t do it.”

1917-1918: Some 100 blacks serve in the U. S. Military. Three blacks, Ernest Gilbert, Valentine B. Johnson, and Samuel C. Thornton, die in service. On the courthouse green’s bronze plaque commemorating those who died in “The Great War,” the names of the three are separated from the 27 whites who died.

October 1919: The Willing Worker’s Club incorporates “to assist in providing proper educational facilities for the colored children of Purcellville, to provide further for the religion training of such children, to equip and maintain a Library and Reading room for such children.” In November, Clarence L. Robey loans them $1,030 for a two-room school “which has been erected.”

October 4, 1920: Of 200 women who register (out of 3,400 eligible to vote for the first time), the Loudoun Mirror notes 18 “colored women.”

ca. 1920: Builder William Nathan Hall buys some seventeen acres at Macsville for a recreation ground for blacks. The land is known as Hall’s Park, open until ca. 1948. It is now administered by the county, but has a new name for a white person.

1922: In this year of public-school consolidation under one county school board, the top salary for a white teacher is $80 a month, for a black teacher, $55 a month.

1921:African American students participate for the first time in the annual school fair, held that year in Leesburg.

1924: Charles Fenton Simms (1850-1924) gives the largest individual gift, $5,000, to the Loudoun County Hospital (founded 1912) “to alleviate the sufferings of the colored people.” The gift probably equaled what Simms was able to earn in a decade.

The Jeanes Fund, a one-million-dollar national fund donated by Miss Anna T. Jeanes of Philadelphia, allows Loudoun to hire a superintendent for Negro schools. But the county does not do so until 1931, and then for only one year.

1925: The average annual salary for white teachers is $836.10, for black teachers, $358.12. Starting salaries are $520 and $315. The yearly cost to educate a white child is $29.27, a black child, $9.81.

Ca. 1925: Wilmer Carey of Washington lays out a baseball field at Purcellville’s Emancipation Grounds. Here, through the 1950s, play Negro teams from Alexandria, Charles Town, Culpepper, Front Royal, Leesburg, Manassas, Middleburg, Purcellville, Warrenton, Washington, and Winchester.

By 1925: Improved roads prompt a few car pools to send black teenagers to the Manassas Industrial School (founded 1894), Northern Virginia’s only accredited high school for blacks.

1930: With two added rooms for two years of high-school instruction, the Leesburg School becomes the first secondary school for blacks. As the Loudoun County Training School, it graduates a class of five in 1935. Diplomas of its last graduating class of 1940 bear the name Leesburg High School.

1931: Neal ‘Kid’ Corum opens his Bowmantown store, and operates it through 1977. Its closing marks the last of the retail businesses owned by blacks in the county.

1931: School board minutes substitute the word “negro” for “colored,” but Negro does not appear again until 1947, when teachers are “negro,” but schools are “colored.”

1932: Loudoun’s first official road map notes three public travelways named for blacks: Ned Davis Lane, near Morrisonville, for a brick maker, Berryman Lane, near Middleburg, for farmer and horseman Raymond Berryman, and Gleedsville Road, for the village by Negro Mountain, founded by Jack and Mahala Gleed.

Blacks from the Bluemont area protest the closing of their school that spring. Train schedules to Round Hill, location of the nearest school, get children to school late and bring them home late. Negro teacher Beatrice Scipio then teaches eight children in her Bluemont-area home for three years.

September 1932: Shadrack Thompson’s burned and mutilated body, dangling from a rope, is found on Rattlesnake Mountain in Fauquier County. A white woman said he had raped her. State and county official deny he was lynched; the NAACP says he was lynched. Locals today affirm the latter position.

1932-1934: The brutal January murder of a Middleburg socialite and her Negro maid allegedly by George Crawford, bring a Howard University defense team, led by Charles Hamilton Houston (Amherst Phi Beta Kappa and Harvard Law), to defend Crawford. Houston’s intellect wins over the jury and for the first time in Loudoun County a black man so accused receives a life sentence rather than death.

1933-1934: Assisting Houston is Howard University law student Thurgood Marshall. The verdict convinces Marshall that blacks can receive justice in the South, and he shelves his corporate law plans for a civil-rights career. In 1967, Thurgood Marshall becomes the first black to serve on the Supreme Court.

1933: Maurice Britton King Edmead from St. Kitts in the West Indies, a Bronx High School of Science grad and Howard University M.D., opens a practice in Middleburg, which continues until 1952. He is the first modern-day black physician, but is not allowed to practice at the Loudoun Hospital.

William “Will” Nathaniel Hall and crew receive the contract to reconstruct George Washington’s gristmill at Mt. Vernon. His builders often number twenty, and he is Loudoun’s largest private employer of blacks.

April 19, 1935: Prompted by the goading of Charles Houston in 1933, Judge J. R. H. Alexander adds to the roll of potential jurors one black, Gus Valentine, a retired gentleman from Leesburg. His wife, Carrie, is Judge Alexander’s maid. Valentine is not called to serve.

1935: The County-Wide League, a union of all Negro Parent-Teacher Associations (PTAs) is organized to improve the quality of education. In 1938, Middleburg blacksmith John Wanzer becomes president, and serves in that capacity until his death in 1957.

1937: Silas Jackson of the Upperville area and George Jackson of Bloomfield are the last of the local slaves to be interviewed, under auspices of the Federal Writers’ Project. Their stories are filled with the details of daily slave life.

Will Brown drives the first school bus for black children, from Purcellville, via Hamilton and Waterford, to the Leesburg School. Busing for white children began in 1925, and by 1937, they have fourteen school bus routes.

April 25, 1938: County funds are expended for health care of blacks for the first time—$100 “for dental clinic for colored children.” White children receive $400, a fair apportionment based on the percentage of blacks to whites in the county’s population.

1939: Under leadership of Gertrude Alexander, who that year becomes the first superintendent of black teachers, the County-Wide League focuses on building a new high school for Negroes.

1939-1945: World War II (U.S. enters war in 1941).

February 1940: Shiloh Baptist Church hosts the first countywide “Negro History Week,” sponsored by the County-Wide League. Speaker Charles Houston points to unacceptable conditions at black schools, lack of equipment, insufficient bus transportation, and unequal pay.

March 15, 1940: The Board of Supervisors “orders to be filed” letters from the County-Wide League, and choral clubs of Providence and Mount Olivet Baptist Churches, urging “immediately a safe place of instruction of the Negro students now going to the Loudoun County Training School.” Next day the League’s same letter, drafted by Charles Houston, is sent to the school superintendent.

March 23, 1940: Getting nowhere, Charles Houston urges formation of a local NAACP chapter. On that day Marie Medley, on behalf of twenty-five persons, including sixteen women, writes the national chapter and encloses their dues.

March 24, 1940: The national NAACP charters a Loudoun chapter. Marie Medley, a Leesburg beautician, becomes its first president.

December 16, 1940: The black community buys eight acres near Leesburg for $4,000, and deeds the land to the Loudoun County School Board for $1. On it Douglass High School will be built. Usually, the school board buys land for schools.

1941-1945: More than 400 blacks serve in the U. S. military. Unlike the World War I memorial, which segregated the 30 names of those who died, the 68 who died in this war—and the 4 who died in the Korean War and the 12 who died in the Viet-Nam War—are named together.

June 1941: Named for the famed abolitionist and educator Frederick Douglass, the new high school receives accreditation and offers a three-year program. It graduates its first class of five.

1942:African Americans students join white students on the Middleburg school grounds to celebrate learning how to manage Victory Gardens.

March 23, 1943: The word “Negro,” rather than the traditional “Colored,” is found in Board of Supervisors ’ minutes for the first time.

1944: The salary gap between the earnings of white and black teachers begins to narrow: The average white teacher earns $1,404, the average black teacher, $1,293.

1944-1945: Both black and white laborers claim that German prisoners of war working in Loudoun orchards get preferential treatment. Blacks are particularly irked that the Germans refer to them as “Nagers.”

December 1946: The first modern elementary school for blacks, eight-room George Washington Carver, in Purcellville, opens. Rosalie McWashington is the principal. The campaign for a new school had begun in 1927.

March 1948: Six-room Banneker School opens at St. Louis, west of Middleburg, the only original school for black children still in operation (now integrated). The School Board wants to name the school “Mercer,” for the magisterial district, but the black PTAs championed Banneker, to honor mathematician and astronomer Benjamin Banneker, who helped to survey the District of Columbia.

September 1948: Four-room Oak Grove School, the first modern elementary school for blacks in eastern Loudoun, opens.

1949: Douglass High School expands to include a twelfth grade level and graduates its first four-year class of twelve in 1950.

1949-1950: Will Hall, a black builder in Middleburg, and his crew of about thirty, build the new Loudoun Hospital in Leesburg.

1949-1952: For two seasons the Douglass High School girl’s basketball team, traveling to away games with the boy’s team, wins the Tri-State Championship under coaches Geraldine Dashiel and I. J. Daniel.

ca. 1949: Episcopalian John W. Tolbert Jr., invited to St. James’ Episcopal Church by Leesburg Mayor George J. Durfey, a sometime employer, becomes the first black man in modern times to worship regularly in a church for whites. When he kneels for his first communion, a woman moves away. Tolbert will later serve as a vestryman at this church.

1950-1953: Korean War

1950: The first black runs for office, Carr P. Cook, Jr., for the Middleburg Town Council. He loses, by two votes.

March 1951: The first community center for blacks opens in Middleburg as Grant School is enlarged. There is a basketball court. The total cost is $59,999; the whites’ community center, built 1948, cost ten times that amount.

1952: George Barrett, science teacher and basketball coach at Douglass High School, writes the first social column for blacks, in the Loudoun Times-Mirror. Fred and Peggy Drummond’s “Lines From Loudoun” follows in 1955; it is still going strong.

1953: The first two rural subdivisions in western Loudoun, Aspen Hill and Leith Village, have covenants stating: “no part of the said property shall be sold, located, or occupied by any individual of African descent.”

1954:Brown v. Board of Education: U.S. Supreme Court declares segregated schools unconstitutional, calls for desegregation of public schools “with all deliberate speed.”

Fall, 1955: Paul Mellon’s Middleburg Horse Training Track at St. Louis opens, and for more than three decades becomes the largest private employers of blacks; from 40 to 60 of them work there.

1956: The Board of Supervisors agrees to build the first modern elementary school for blacks in Leesburg, Douglass. The building is complete by early 1958.

1956-1959:Senator Harry F. Byrd, Sr. leads “Massive Resistance” campaign against school integration in Virginia. State and federal courts overturn Virginia laws and order desegregation to proceed, but delayed in Loudoun and elsewhere.

August 1956: The Board unanimously passes this resolution forwarded by Commonwealth’s Attorney Stirling M. Harrison: “In the event the integration edict is imposed upon the public school system there will not be forthcoming any funds for the maintenance and operation of any school.”

March 1957: Purcellville Library, the one county public library, desegregates after Samuel Murray takes the library to court for refusing to loan him a book. Only after the Board of Supervisors and Town Council threaten to cut off funds do library trustees vote, 7 to 5, to keep the library open.

1957: Waterford’s black school (grades 1-8) closes; children are bused to a black school in Leesburg.

1959-1975: Vietnam War

By 1959: Without giving public notice, the school board allows black children to enter a white school if their parents come to the board offices and get a blue consent slip. No one can recall a Negro child going to a white school before 1963.

1960: Dover’s Glanwood Moore organizes the first black Boy Scouts, Troop 1168, under sponsorship of the Banneker PTA. Under scoutmaster James Roberts, it merges with white troop 953 in 1970.

ca. 1960: Clint Saffer, owner of the Leesburg mill and chairman of the Democratic Party, asks John Tolbert what he thinks of integration. John replies, “ Clint, if you had twenty white-faced Angus and one black-faced Angus, would you built a separate barn for the black-faced Angus?”

By 1960: To circumvent the unequal treatment afforded blacks by the “blue slips,” the school board requires all children to present blue slips indicating whether they’d prefer to attend a “black” or a “white” school.

April 19, 1961: Two Howard University students sip cokes at Flournoy’s Drug Store, Middleburg, in the first instance of lunch counter desegregation brought on by threat of a mass demonstration of Washington NAACP and CORE members. Father Albert Pereira, President John F. Kennedy’s priest, and Mayor Edwin Reamer convince eateries to desegregate so they will not embarrass the President, who worships in town on Sundays

April 29, 1961: At B. Powell Harrison’s suggestion, a meeting between leaders of the races forestalls a Washington NAACP and CORE demonstration in Leesburg. Town drug store lunch counters serve blacks.

By 1962: Construction of Dulles Airport razes the 1880s predominantly Negro village of Willard. Some blacks contend the airport would not have been located there had the area been largely white.

February 1, 1962: Walter Murray’s ten-pin Village Lanes bowling alley on Catoctin Circle, Leesburg, opens to all. The segregated duck-pin alley closes shortly.

July 16, 1962: Upon motion of Jefferson District (now part of Catoctin District) Supervisor James E. Arnold of Waterford, the Board of Supervisors rescinds the August 1956, opposition to the school integration edict by a four-to-one vote.

Summer, 1962: Black teenagers have been taking nightly dips in the whites’ Middleburg Community Center pool. Center president Howell Jackson suspects black activist William McKinley Jackson of encouraging the trespassers. A “Jackson-to-Jackson” confrontation prompts Howell to desegregate the pool when the public schools integrate.

1962: A dozen blacks request the state to admit them to the county’s whites’-only high schools, and eight blacks sue Loudoun for its segregated schools. A federal court orders the county to comply with the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decisions desegregating public schools.

Robinson’s Barber Shop, under the new management of Negro war veterans Raymond Hughes and Horace Nelson Lassiter, removes its “Caucasians Only” sign.

September 1963: Father Albert Pereira, the county’s Catholic priest, and Lincoln-area ladies have planned the integration of the new Loudoun Valley High School; only the brightest blacks will enter. Ten integrate that school, and a black girl is salutatorian. There are no problems.

1964: Civil Rights Act andVoting Rights Act

September 1964: One black girl enters Loudoun County High School. Ten black students follow the next year. There are no problems, except for the common taunts of “nigger.”

August, 1965: A Federal court order sues school officials “for still operating on a dual system,” and orders “all Loudoun schools be integrated on both pupil and staff levels no later than the 1968-69 school year.”

Summer, 1965: Without protests, blacks enter the whites’ section of Leesburg’s Tally-Ho movie theater.

Late summer, 1965: Blacks file suit to swim in the Leesburg Volunteer Fire Company’s ‘public’ pool. The firemen have the pool filled with rock and concrete, and it never opens again. Leesburg does not have a public swimming pool until 1990.

Fall, 1965: Sterling Park, the first large subdivision, has its first black family among some 400 others. Blacks are reluctant to move to what they perceive is a rural segregated county.

1965: The Middleburg Community Center is finally integrated; the NAACP holds its twenty-fifth anniversary there. The town tows two illegally parked guests’ autos and firecrackers explode outside the center.

August 1966: William Washington and two whites, Mark Crowley and Pat Shoaf, integrate Purcellville eateries by having lunch at the Tastee-Freeze. Mr. Crowley recalls: “I got a hate stare I never will forget. None of us enjoyed our lunch.”

September 1967: The Loudoun County Emancipation Association holds its final Emancipation Day celebration; in 1970, they sell the ten-acre Emancipation Grounds for $20,000; the buildings soon decay.

September 1967: The white high schools begin recruiting Douglass’s black athletes. Chick Bushrod, one of those recruited, recalls “they treated us like livestock.” The 1968-1969 Loudoun County High basketball team features 12 blacks and 3 whites.

November 1967: The first blacks to hold elected office are contractor Charles ‘ Jack’ Turner of Middleburg, and brick mason Basham Simms of Purcellville. Both town councilmen are elected again and again.

April 1968: After Martin Luther King’s assassination on the 4th, black students at Loudoun Valley High School hold an assembly to talk, pray, and sing spirituals.

The white county baseball league integrates as Round Hill plays the Coates brothers: Wilbur at shortstop and pitching, batting third; Ralph, catcher, batting clean up. In uniform, Wilbur hitchhikes from Gilbert’s Corner each Sunday.

May 1968: The Leesburg firemen will not let an integrated baseball team play at Firemen’s Field, and closes the field that year.

The final class of Douglass High School, forty seniors, graduates. The commencement theme is “A Past to be Proud of.” The last all-black classes at Banneker, Carver, and Douglass Elementary Schools also graduate.

September 1968: Round Hill, playing the Coates brothers, meets Leesburg for the league championship at Purcellville’s Fireman’s Field. Wilbur scores from second base on a single to win the game. Leesburg threatens to quit the league.

Annette Scheel, the county’s first reading specialist, is the first public-school staffer to integrate the schools, teaching at the all-black Douglass High School for two months.

December 1968: The U. S. Department of Justice again threatens to sue school officials for its policy of token integration.

May 1969: School Superintendent Clarence Bussinger retires after twelve years of thwarting integration. Under new superintendent Robert Butt from Orange County, the public schools are finally integrated in the 1969-1970 school year—in true “I Byde My time” fashion. Fifteen years have passed since the Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954.

1970: All Loudoun restaurants serve African Americans.

1970: In slow decline since the war’s end, the black population drops from 18.8 percent of the county’s persons in 1950 to 12.5 percent, or 4,648 or a population of 37,150.

1973: Leesburg’s Loudoun House, the first subsidized low-cost housing complex, opens. Of its some 250 families, usually more than 80 percent are black. To the established of both races, the development becomes a symbol of urban ills.

1976: Charles P. Poland’s history, From Frontier to Suburbia, presents the first published coverage of the county’s black heritage.

June 10, 1976: Eugene M. Scheel’s detailed Loudoun Times-Mirror chronicles twenty-four black villages and hamlets begin with a history of Bowmantown. Through a grant from Purcellville’s Robey Foundation, he also begins recording several oral histories of African-Americans. For further information see Deborah Lee’s African American Communities and Map.

July 1976: Carr P. Cook Jr., is the first black school board appointee, for Mercer District.

1976: John W. Tolbert becomes a member of the Leesburg Town Council. He will later serve as Leesburg’s vice-mayor.

1977: Middleburg’s James Roberts breaks the color line of the traditional all-white volunteer fire departments and becomes a town fireman.

May 1978: Rosa Carter retires from a 52-year teaching career, the final 30 at Banneker Elementary School. For ten years afterwards she volunteers her services. She asserts that blacks always “got the second best,” but her credo is “give it your best.”

1980: Decline of farms, especially dairy farms using black labor, leads to the first single-digit percentage of blacks to total population: 8.8 or 5,018 among 57,427 persons.

August 1983: Middleburg’s Windy Hill Foundation, buoyed by the hard work and funds of Rene Llewellyn, organizes and begins to renovate the homes and surrounds of this early-20th-century black ghetto.

By November 1983: “An enlightened bulldozer” razes the one truly integrated graveyard, Leesburg’s Potter’s Field: The acreage is worth $200,000 to the town. Some 200 interments, from 1839 to 1948, are uncovered. A single marker in Union Cemetery marks the remains.

Spring, 1984: The Waterford Foundation, under the leadership of Kathy Ratcliffe and Bronwen Souders, opens the 1867 Colored School to 3rd and 4th graders to role-play an 1880’s Waterford students day in a segregated school.

February 1, 1987: More than 300 at the Middleburg Community Center—the first large integrated gathering other than a school or sports event—listen to area black church choirs sing spirituals to celebrate the town’s 200th anniversary.

1990: The percentage of blacks decreases to a low of 7.1 percent of a total population of 86,129. In the western part of the county, the percentage has dropped from a 1950’s percentage of 20 percent to 4 percent.

February 17, 1990: The NAACP sponsors its first program in Loudoun County honoring Black History Month at the Douglass Community Center. The young adult choir of Leesburg’s Mount Olive Church presents the drama “Black Historical Expressions.”

Summer, 1991: Brad Curl of Taylorstown begins to bring poor black youngsters from Washington, D.C. to a summer camp at Glaydin School, near Lucketts. By April 1994, the youngsters and teenagers stay full time and attend Loudoun schools.

1991: Leesburg names a road, Tolbert Lane, to honor John Tolbert, councilman 1976-1990, and a quiet presence for civil rights since coming to Loudoun in 1931. No other feature on the landscape had been named for a local black citizen since 1932.

November 1991: The NAACP points out that 6 percent of public school teachers are of minority background, while 14.6 percent of the county’s population has minority backgrounds.

1992: Martin Luther King memorial installed on Courthouse grounds.

August 1992: Gladys Jackson Lewis, former Waterford resident, organizes a day for “Blacks who have moved away,” at the 1891 John Wesley Methodist Church. Some fifty attend this first county reunion of old-timers.

1993: Relatives of the disbanded Emancipation Association members ask the Loudoun Restoration and Preservation Society for a grant to restore the Emancipation Grounds’ surviving building, the 1910 log-cabin headquarters. Their request is denied.

Christmas, 1995: Joy Johnson of the Community Church, Sterling Park, begins the congregation’s outreach ministry to Loudoun House.

February 24, 1996: The NAACP holds a 2-½ hour Black History celebration at Mount Olive Church. The message is Christian compassion. A speaker notes: “Don’t let the evils of Washington and Baltimore reach Leesburg.”

February to May, 1996: Curator Betty Flemming, along with Mary Lee Perry and Mary Randolph of the black community, organize at the Loudoun Museum the first exhibit in the county featuring African-American art. It is titled, Discovering Our Black American Heritage: Handmade Items from the Community, Past and Present.

March 1996: Jim Vaught, pastor of King of Kings Worship Center, Purcellville, reaches out to black ministers. They meet weekly with white clergy, and soon their congregations worship at each other’s churches.

August 3, 1996: Descendants of slaves and freed blacks who labored at Oatlands, the plantation of George Carter and his widow, Elizabeth—owners of the largest number of slaves in the mid-19th century—hold a reunion on the grounds.

September 1, 1996: Some 19 black and white congregations and their ministers, from Leesburg and western Loudoun, attend “Heal,” a picnic and preaching promoting reconciliation among the races.

September 1996: Christian Fellowship Church moves from near Reston to Ashburn, and under leadership of the Reverend James Ahlemann and the Reverend Odelle Moore—the first black minister of a largely white congregation—becomes the county’s first truly integrated church; some 15 percent of its worshippers are black.

November 1996: At the urging of Chauncey Smith, NAACP activist, the county approves an affirmative-action policy. Then, in accord with national policies, the county rejects the idea. That year county minority employees comprise 5.6 percent of the work force. The total minority population is at 10.3 percent.

1996: Brenda Stevenson’s book, Life in Black and White, brings ante-bellum Loudoun into national scholarly focus. She espouses the opinion that the realities of slavery precluded a normal household.

March 1997: Under leadership of the Reverend Tom Smith, Christian Fellowship Church begins its ministry to Loudoun House.

June 1997: Mike Holden of Circleville, near Lincoln, founds “Loudoun Men of Integrity,” a Christian group, to promote unity among the races. Nine Leesburg and western Loudoun churches, three of them black, begin to hold monthly men’s breakfasts.

February-April, 1998: Elaine Thompson of Hamilton spearheads the Loudoun Museum’s Emancipation Society exhibit. The souvenir booklet, “Let Our Rejoicing Arise,” commemorates the Society’s achievements. Many mementos will shortly become part of the museum’s permanent collections. See Loudoun County Emancipation Association.

September 1998: As a development proffer, two acre that include stone slave quarters, near Arcola, are donated to the county. It agrees to seek funds to renovate the building—the first derelict structure important to black history to receive such notice.

September 1998: Of the county’s work force, 10.3 percent are minorities; 7.1 percent are black. These figures are right in line with the county’s percentage of blacks and minorities, the former numbering some 10,000.

1998: In July, residents of the 248-apartment Loudoun House, occupied by many low-income minority families, receive eviction notices, effective March 1999. A new owner is planning a complete renovation. Residents find that alternate housing will accept rental-assistance vouchers.

February 1999: Christian Fellowship Church, near Ashburn, with some 2,600 attending Sunday services, has Loudoun’s largest congregation, and is truly integrated: 20 percent black and some 10 percent other minorities. The Reverend Arlie Whitlow’s Community Church in Sterling, with 600 Sunday worshippers, is about 12 percent black.

March 1999: Eugene Scheel begins teaching the public-school system’s first local African-American history course for teachers.

By 2000: A rash of government grants for black history result in the publication, within four years, of a book, two walking tours, a driving tour highlighting black communities, and an architectural survey of historic homes of African-Americans. See Walking Tour.

February 2000: The Loudoun Museum presents an exhibit: Courage My Soul: Historic African American Churches and Mutual Aid Societies, curated by Elaine E. Thompson and Betty Morefield. See Churches.

April 2000: The Lincoln Preservation Foundation decides to raise funds to repair the 1885 Grace Methodist Church, vacant since 1949. The foundation’s goal is to garner $100,000 by 2004.

June 2000: An anonymous $50,000 donation to Friends of the Thomas Balch Library leads to organization of the Friends’ Black History Committee. Its mission: “to preserve, collect, promote, and share the history of African-Americans who lived in and contributed to the emergence of Loudoun County.” The donor requested that a room at Balch be named in honor of African Americans. The committee selected the first secretary of the Loudoun County Emancipation Association, Howard W. Clark Sr.

2002: The latest population estimates for Loudoun note that of its 196,300 persons, minorities account for 21.7 percent of the population: Asians, 7.5 percent; Latinos, 7.1 percent; Blacks, 7.1 percent.

2003:National Park Service designates Courthouse as “Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Site.”

Winter 2003: Only in eastern Loudoun and in the newer sectors of Leesburg—where most minorities live, having newly moved to the county—is society fully integrated. In established Leesburg and western Loudoun blacks usually live in separate areas, and nearly always descend from old-line county families. By and large, they and white society remain socially apart.

2015: Board of Supervisors reserves $50,000 toward a memorial “to honor and remember the enslaved that were sold on the courthouse steps and those individuals from Loudoun County who fought for the Union during the Civil War.”

2016:Loudoun County Schools commissions the Edwin Washington Projectto document the experiences of African Americans in segregated schools.

Bibliography

Each of the following publications has as its major focus people, places, and events. The plums in each category are: the two Essence of a People volumes, African American Heritage Trail (Leesburg), and A Rock in a WearyLand, A Shelter in a Time of Storm.

People:

The Black History Committee, Friends of the Thomas Balch Library. The Essence of a People: Portraits of African Americans Who Made a Difference in Loudoun County, Virginia. Leesburg, Va., 2001.

The Black History Committee, Friends of the Thomas Balch Library. The Essence of a People II: African-Americans Who Made Their Worlds Anew in LoudounCounty, and Beyond. Leesburg, Va., 2002.

The first volume, containing twenty-two essays by various contributors, focuses on persons nominated for the honor of having a room named for them at the Thomas Balch Library.

The second volume, containing fifteen essays, is divided into two sections: “The Road to Freedom” and “The Battle for Equality.” The essays, written for the most part by persons intimately connected with their subjects, are heartfelt and often trenchant. Both volumes are illustrated. The first volume is not indexed.

Follmer, Don, and Robin Lind, Mary Grace Lucier, Karen T. Richardson, and others. Loudoun Harvest. Leesburg: Metro VirginiaNews, 1973.

Includes vignettes of many African Americans, as well as whites.

Other personalities are given brief biographies in the following articles by Eugene Scheel in the The Washington Post Loudoun Extra sections for: Feb. 6, 2000; Feb. 25, 2001; Sept. 6, 2001; March 17, 2002; July 7, 2002; May 18, 2003, Oct.19, 2003.

Places:

History Matters.

With a substantial grant in 2002 from the county and a donation from the Black History Committee of Friends of the Thomas Balch Library, this D. C. firm completed a survey of 200 historic homes of African Americans. The survey should be complete by 2004.

Lee, Deborah A. African American Heritage Trail. Leesburg, 2002 .

Funded jointly by the Loudoun Museum and Friends of the Thomas Balch Library, this illustrated gem ranks at the forefront of all walking tours.

Lee, Deborah A. Loudoun County’s African American Communities: A Tour Map and Guide. Leesburg, Virginia: The Black History Committee, Friends of the Thomas Balch Library. 2004.

This booklet briefly summarizes the history and highlights of the communities. Illustrated and with a small map. See African American Communities.

Scheel, Eugene M. The History of Middleburg and Vicinity. Middleburg: The Middleburg Bicentennial Committee, 1987.

The only substantial town history to cover its black heritage. Illustrated with maps, indexed.

Scheel, Eugene M. Loudoun Discovered, 5 vols. Leesburg: Friends of the Thomas Balch Library, 2002.

Often with great detail, these books feature most of the African-American villages. Illustrated and indexed, with maps locating the villages. The initial Loudoun Times-Mirror articles (1976-1983), from which these expanded essays were drawn, often contain additional information and other photographs.

Snedegar-Spicer, Eula Louise. Black Schools in Western Loudoun County before Integration. M.S. Thesis, Shenandoah University, 1998.

A detailed school-by-school account, including a listing of teachers.

Souders, Bronwen C. and John M. Share With Us: Waterford, Virginia’s African-American Heritage. Waterford: The Waterford Foundation, 2002.

A fine thematic walking tour, although not quite as detailed as Lee’s Leesburg jaunt. Illustrated and with maps.

Thompson, Elaine and Betty Morefield. Courage, My Soul: African American Churches and Mutual Aid Societies.Leesburg: The Loudoun Museum, 2000.

Contains brief write-ups of the above, with photos of the buildings. See Historic Churches and Church Photographs .

Events:

McGraw, Marie Tyler. Northern Virginia Colonizationists. Northern VirginiaHeritage, V.1 (February, 1983).

A reworking of a chapter from her 1980 George Washington University Ph.D. Dissertation, “The American Colonization Society in Virginia.” See Loudoun County ACS and Lucas-Heaton Letters .

Poland, Charles. From Frontier to Suburbia. Marceline, Mo.: Walsworth Publishing, 1976.

The county’s only comprehensive history deals ably and fairly with its black populace. Includes illustrations, maps, and is indexed.

Scheel, Eugene. Map of Loudoun County Leesburg: Loudoun Association of Realtors, 1990.

The map’s scale is one inch to one mile. Shows exact locations of nearly all the Negro Schools, churches, neighborhoods, and differentiates between standing and no-longer-standing buildings.

Scheel, Eugene. The following Washington Post articles in the “Loudoun Extra ” section cover these subjects:

The Underground Railroad, May 27, 2001; July 7, 2002;

Emancipation Day, September 17, 2000;

Emancipation Proclamation, January 5, 2003;

Integration of Loudoun Baseball, July 20 and August 3, 2003;

Integration of the Library, April 8, 2001;

Integration of Schools, May 21, 2000.

Douglass Girl’s Basketball, February 1, 2004.

Souders, Bronwen C. and John M. A Rock in a Weary Land, A Shelter in a Time of Storm: African-American Experience in Waterford, Virginia. Waterford: Waterford Foundation, 2003.

Culled from numerous sources, this resume of life in a predominantly Quaker town is enhanced by excellent photographs, and excerpts of Virginia acts covering blacks. Indexed.

Stevenson, Brenda. Life in Black and White: Family and Community in the Slave South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. Written in the detached style of the Yale University Ph.D. dissertation that it once was, this 452-page tome deals mostly with Loudoun County. Her thesis: Black families were different from white families because they were enslaved. Illustrated and indexed.

Thompson, Elaine. Let Our Rejoicing Arise: Emancipation Day in Loudoun County. Leesburg: The Loudoun Museum [1998]. Valuable for its photographs. For a more comprehensive history, see the Scheel Washington Post article, September 17, 2000.