Lovettsville - A German Settlement

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

Lovettsville history web site »

When colonists from the eastern seaboard began to move westward in the latter part of the 1600's the Iroquois Indians were the scourge of an area reaching southward from New York across Pennsylvania and Maryland into northern Virginia. The colonists and other Indians feared them alike. In 1722 Sir Alexander Spotswood, Governor of Virginia, joined the governors of New York and Pennsylvania to consummate the Treaty of Albany with the Iroquois Nations. By terms of the treaty, the Iroquois were prohibited license or passport of the Governor of New York. Subsequently, the treaty was interpreted to apply to all Indians; consequently, they played only a very insignificant role after 1722 in the history of northern Virginia. There is little doubt that the treaty opened up this locality as a suitable frontier for white settlement.

About 1732 the first German families founded the settlement that ultimately became Lovettsville. This was happening about the same time that George Washington was born on a plantation about 90 miles southeast of the settlement. In order to understand the motivation and character of these people, we should go back to Germany and that part of its Rhine River Valley called the Palatinate or Palatine States. The Palatinate had been a peasant land of small towns and farms populated by an industrious, God-fearing people of peasant stock. However during the 17th century, Europe was seething with unrest, which erupted into several devastating wars. In the early half of the century, there was the Thirty Years War. Hardly had the Palatines recovered from the agonies of it, when they were invaded and occupied by Louis XIV of France from 1688 until 1697. Then in 1703 came the War of the Spanish Succession, which lasted another 10 years. During this time, many of the Palatines reached the end of their endurance and decided to seek refuge overseas. Like many of their countrymen, they first went to England. Here they found life less harrowing, but it was neither the kind of life they had known nor the kind they were seeking. Work was hard to get, and they were forced to accept assistance too often. To be "beholden" to anyone was against every principle of their self-sufficient nature, and they felt unwelcome. So it was not surprising that they soon began migrating to the American Colonies.

After arriving in America, many Germans immigrants went to New York, but far more of them chose Pennsylvania where 40 to 50 thousand of them found homes between 1702 and 1727. By 1747 the Germans comprised about 60 percent of all the people in Pennsylvania. In the German language, the official name for Germany is "Deutschland" and so they came to be known as the "Pennsylvania Dutch," although they were not of Dutch descent. In 1730 following the opening for settlement of the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia, many Pennsylvania Dutch went there to establish home and communities. This valley was only a few miles west of the site of present day Lovettsville. A year or so later, 65 or more families came into and settled in the area that now surrounds Lovettsville. In a book entitled The German Settlement, by Briscoe Goodhard, there is a list of the names of 71 families, which he says comprised the colony by the end of 1733. Whether these people came directly from Pennsylvania or by way of the Shenandoah Valley is not known. What the founders called their new settlement is also not known. However, very shortly "outsiders" began calling it "The German Settlement," and the name stuck for about 100 years. From the very beginning, these people were prosperous, but their prosperity was no accident. They were sturdy by nature; and strengthened by past hardships, they did not shrink from hardships of life on this untamed frontier. With rare foresight and self-reliance, they planned their community. They saw to it that within their own ranks there were artisans who could work metal, make clocks, weave cloth, cobble shoes, make furniture and tools, and distill liquor. With them they brought horses, cattle, poultry, swine, sheep, and probably dogs and cats.

They had chosen to become Virginians, but they continued to live as they had in the old country. They spoke only the German language and followed their "Old World" customs, refusing steadfastly to be dependent upon others. They were geographically and socially removed from the English settlements to the south and east, and continued in fact as well as in name to be Germans. In contrast to the colonial costumes of the English settlements of Virginia, the people of The German Settlement dressed in the simplest kind of homemade clothing. Thus, it is quite clear that these people followed a way of life peculiar to them alone. So, why had they chosen to become Virginians? Of course, the availability of fertile farmland attracted them, but there were undoubtedly other reasons. Perhaps their objectives are best explained in a paragraph take from an article written by Irvey W. Baker, one-time Chairman of the Board of Supervisors of Loudoun County. Quote, "Their aim was to discover the American way of life, as it opened great opportunities in a land of continental proportions, and in its immense resources they could always find a way for willing and competent hands to become part heirs of this great estate."

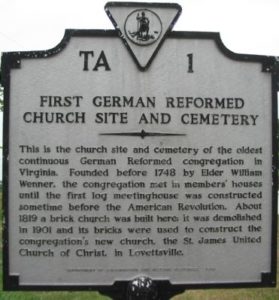

Now having come from Pennsylvania, a colony which had had religious freedom since William Penn, these people were now settling in a colony where everyone was obliged to attend the Church of England. In Virginia, church and state were not separated. In fact, they functioned reciprocally as the parish rolls were used to collect taxes. Nevertheless, it appears that The German Settlement ignored the dictates of both church and state, for they established their own Reformed Church, which played a prominent role in shaping the early life of The Settlement. Their early church leaders performed the functions of both preacher and teacher. Although public education did not become common until many years later, the church leaders saw to it that all of the children were taught to read, write, and cipher.

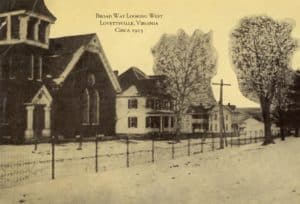

Life in The German Settlement was simple, but not really primitive. Their houses, their church, and other buildings were log cabins, but they were not necessarily "small, crude or rough," as frontier housing is often described. Some log houses, still in existence in the area, are actually quite commodious. That is not to say that those still existing are some of the original ones, but they do reflect that the people of The Settlement did prosper and liked to live comfortably, though simply.

The richly costumed, minuet dancing, dewigged, slave holding, planter of English Colonial Virginia often considered their German neighbors stupid and uncouth. The Germans did nothing to correct that impression. Little did they care what others thought of their plain dress, country manners, and guttural speech, as long as they were free to live apart in their own small settlement and practice the agricultural know-how in which they excelled. If the Germans appeared awkward and unsophisticated to their gentleman neighbors, maybe they were; but if the Germans appeared stupid to the gentleman, the gentlemen were wrong. The Germans we plain, "Yes" but stupid and dull, "Never."

The period between the years when The German Settlement was being established (1732-50), and the Revolutionary War is rather obscure in the history of The Settlement. However, there were a few significant occurrences that affected The Settlement. One was the French and Indian War (1754-63), which was waged on the western frontier of the English Colonies. The western frontier of Virginia was just across the Blue Ridge Mountains, a few miles west of The Settlement. Some of the military action and Indian raids took place in the Shenandoah Valley, west of the mountains. None of the fighting took place east of the mountains, so many of the terror-stricken Pennsylvania Dutch, who had previously settled in the Shenandoah Valley came streaming over the mountains into The German Settlement seeking safety. Many of them stayed, thus expanding the local population. Another thing that happened was the creation of Loudoun County in 1757 out of what had previously been a part of Fairfax County. Still another thing was the arrival in about 1765 of a group of German Lutherans. They settled down at once among the earlier inhabitants and established their church, which was the predecessor of the present day New Jerusalem Evangelical Lutheran Church.

When the Revolutionary War broke out, there was a divided home front in the Colonies. Where the population was primarily made up of British subjects, all did not support the cause of liberty. Many Englishmen went home, thousands fled to Canada, and others like the Quakers simply withdrew as much as possible and kept quiet. In contrast, there was little division of sympathy in The German Settlement. Almost every man of military age volunteered to fight on the side of the patriots, for they remembered the reasons for their ancestors having left the Rhine River Valley. Most of them served valiantly in Colonel Charles Armand's Legion. Colonel Armand was a French nobleman, who volunteered to help the Colonies in their struggle. He spoke German fluently and was highly respected by his men. One who did not serve under Colonel Armand was Johannes Lorenz Eberhardt, called Laurence.

Following the Revolutionary War, The German Settlement settled back into its pre-war way of life. In 1820 David Lovett, a descendant of one of the original families, subdivided his property into quarter-acre "city lots," which set off a building and business boom, and put The Settlement on the map as a full-fledged rural village. The people called it Newtown until 1828, when its name was officially changed to Lovettsville. In 1836 the Virginia General Assembly passed an act to establish Lovettsville as a town, however it was not until 1876 that it was fully incorporated as a legitimate Corporate Town.