Hillsboro, Virginia

200 Years Later, 'Town Made of Stone' Retains Its Idyllic Character

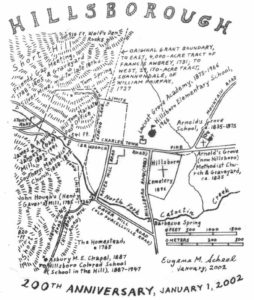

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

More on HiIlsboro history

Hillsboro was 200 years old in 2002. The town was described by an early traveler as "a town made of stone, even to the pig styes." And, if the date on the town's welcoming signs is correct -- "ca. 1752" -- 2002 also marks the 250th anniversary of Hillsboro's predecessor, a huddle of houses and a mill known as The Gap.

The Gap was an obvious choice for a village name, for then as now the cascading North Fork of Catoctin Creek, on its eastward rush toward the Potomac River, splits Short Hill in two. A full 500 feet below the two hillside crests stood Samuel Bucher's mill and its "tenement," an old English word meaning dwelling place.

The Gap grew as the number of mills increased and their size expanded. John Hough rebuilt Bucher's Mill in 1785, and by 1797, he had a second mill built 1,700 feet upstream. By 1802, the village was approaching its current size of 96 residents, and a post office was established Jan. 1.

Striving for a more alluring name than The Gap, Mahlon Roach, the first postmaster, chose Hillsborough, meaning "a shelter in the hill."

The classic spelling was essential between 1806 and 1825, for during those years there was a Hillsboro post office in Culpeper County, 38 miles southwest of the one in Loudoun County. That village, also largely made of stone, is now in the Blue Ridge foothills of Rappahannock County.

Indeed, the Hillsborough spelling was official through 1893, when the U.S. Postal Service dropped the last three letters. Others, however, persisted in using the old spelling -- especially town historian James Edward Copeland, who died in 1937 at 92. His grandson, Edward Virgil Copeland, recalls that "he just hung on to it; he was somewhat of a traditionalist."

I spoke with the younger Copeland last week at The Homestead, on the outskirts of Hillsboro. The farm has been in his family since 1765, when Edward's great-great-great grandparents, David and Deborah Copeland, settled there and had the stone house built. Their son, James, remained on the farm, enlarging the house in 1804, but the other son, Richard, moved to town and was among Hillsborough's 19 property owners in 1802.

After the post office was established, the 19 got together and petitioned the Virginia General Assembly to sanction Hillsborough as a town, and the legislators obliged on the last day of 1802.

The 19 had chosen seven trustees, whose main job was to "make such rules and orders for the regular building of houses . . . to settle and determine all disputes concerning the bounds of lots" and to ensure that each house built be "equal to twelve feet square, with a brick or stone chimney."

The standard rural house size in Virginia then was 16 feet by 20 feet, but a stone house took more time to build.

Postmaster Roach was a trustee, and so was mill magnate John Hough, owner of several other mills in northwest Loudoun and a resident of the Waterford area.

Hough's two Hillsborough mills were unique, for they stood close together on a watercourse 20 feet wide. Most mills on the same stream were at least a mile apart, so the "upper" mill would not capture water needed to feed the lower mill's wheels.

Hough's enterprise made Hillsborough the first two-mill town in the Virginia Piedmont, and the pair accounted for the town's prosperity in the first half of the 19th century, when they were run by Hough's son, Mahlon.

The upper mill, built of logs, was owned by James C. and Aquila Janney in the 1830s and burned in 1837. The Janneys then rebuilt in stone, naming their new 3 1/2-story manufactory "The Gap Mills," a name it would keep until it ceased operating in 1940 as the last mill in the area to grind flour.

When it was dismantled by builder Claude Honicon the next year, old-timers asserted that the wind blew through town for the first time in more than 100 years. Its stone was used to build a gas station in Hillsboro that is now a piano shop.

Among James Janney's nine children was John Janney, whose job was to drive his father's six-horse wagon team to Alexandria, where flour commanded a high price for export to Europe. Writing in the Loudoun Mirror in the summer of 1926, historian James E. Copeland noted that young John Janney "was considered one of the most expert waggoners on the road."

At the old log mill, John Janney read law books and was soon admitted to the Virginia Bar, "to the surprise of friends and associates," Copeland recalled. Janney would later achieve fame as the man who lost the U.S. vice presidency by one vote because he did not vote for himself and as president of Virginia's secession convention in 1861.

Mahlon Hough's lower mill achieved fame in 1844, when it became Henry Gaver's woolen mill, one of a handful in Loudoun. Its water-powered looms spun out yarn used to produce carpets, clothes, blankets and counterpanes, some still owned by Loudouners even though the mill's looms stopped in 1895. Gaver's Mill was later used for storage before being torn down in 1936.

The mill's heyday came in 1859-1860, when it manufactured wool for the uniforms of the Hillsborough Border Guards, organized in October 1859 to help put down John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry.

Recalling their raiment, Copeland wrote: "This company was uniformed in gray swallow tail coats with three rows of Virginia buttons on the kite shaped breasts of the officers' coats and on the black breasts of the privates.

"The officers wore golden tinseled epaulettes and golden braid on the legs of their pants, and black stripes on the legs of the privates' pants; golden stars on the skirts of their coats; red feathers in the high gray caps of the officers and black pompom, in the privates' caps."

Hillsborough had a silver mine that also whetted Copeland's prose, especially after he came upon an anonymous Loudoun Mirror article of October 1922 about the mine, which had been worked since Colonial times and was one of Loudoun's two silver prospects of that era.

Two strangers caused a "sensation" in Hillsborough in 1872, the article said, when they showed up in town and "finally confessed that they were in quest of a silver mine which had been discovered and worked by their great-great grandfather in the time of the French wars and Braddock's defeat [in 1755]."

Copeland, 27 in 1872, remembered that the strangers were the Lindsey brothers, "unheralded and unknown. They claimed relationship with Benjamin Leslie," an early settler, who had taken silver from the mine and had fashioned the metal into tableware. To prove their claim of mineral rights, the Lindseys "produced spoons that were still owned and cherished by the family as heirlooms."

The Lindseys also showed the town trustees an agreement between their family and James C. Janney, who had owned the silver mine, just west of his Gap Mills. The agreement gave the Lindsey family the right to prospect for silver and other metals with the stipulation that Janney would receive one-third of the take.

The Lindseys "worked faithfully during the summer and the following year," noted Copeland, for townsmen had told them that in the 1820s, Janney observed that earlier prospectors uncovered a windlass, picks, other mining tools and silver ore at a depth of 18 to 20 feet.

But, Copeland recalled, the Lindsey brothers could not find the mine "and returned to their home in Illinois with depleted pocket books." People still search for the mine, a few yards east of Gap Mills' old dam across Catoctin Creek.

Almost as obscure as the mine is the origin of the name Hill Tom, which graces the marquis of the town's market-cum-post office. Again, we are indebted to James Copeland, for he knew Hill Tom, a free Negro "who long ago eked out a living by trapping rabbits and other game during the season and working at odd jobs during the summer. He wore a beard -- an unusual appendage in the day."

The late Glenn Roberts, who ran the Hill Tom Market from 1950 to 1985, told me that his father, Spencer Roberts, gave the store its name when he opened it in the late 1930s.

The elder Roberts had heard of Hill Tom when he took responsibility for upkeep of the five-gallon-a-minute Hill Tom Spring in the late 1920s. The Short Hill slopes by the spring had been Hill Tom's favorite hunting grounds, and the spring had taken his name by the middle of the 19th century.

Copeland wrote in 1926 "that perhaps one hundred years ago," Samuel Clendening Jr. "cut and hauled pine logs from the government land on the Blue Ridge to Hillsborough and which were fashioned and laid for a conduit to convey water from Hill Tom Spring to Leslie's tanyard and intermediate points."

By 1858, at least six town homes were connected to the wooden conduit, and the town soon had two public hydrants, which emptied into two horse-watering troughs. In 1887, the state chartered the Hillsboro Water Co., with six trustees who were to maintain the system. But with the tannery closed and a population that had declined to 131 in 1900, the trustees felt that the system could maintain itself.

When Spencer Roberts took over, he replaced the wooden pipes with galvanized iron ones in 1935 and installed a two-inch water main through town. A 50-cent monthly fee from each house on the system paid for the improvements.

In 1953, the town dissolved Hillsboro Water Co. and took over the spring and its system, charging residential customers $2 a month, a fee unchanged through 1975.

Today, the 31 buildings hooked to the Hill Tom system pay $12.50 a month per person, with a maximum monthly charge of $50. For the past several months, spring customers have been under a boil-water alert after contaminants were found in a water sample. State officials have ordered the town to devise a water-treatment plan, an expensive and controversial matter.

Hill Tom Spring, the mills and the mine were three facets of the 250-year history of the fourth smallest town in Virginia in population and second smallest in size. The winners? Columbia in Fluvanna County, with 49 residents, and Quantico in Prince William County, with less than 25 acres.

But can they match picturesque Hillsboro, still idyllic in the antediluvian gap of Short Hill?

Copyright © Eugene Scheel