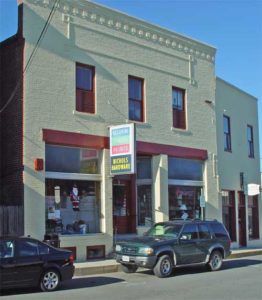

Nichols Hardware Store

Nichols Hardware Store131 North 21st Street

Purcellville, VA 20132

Phone: 540-338-7131

It has been in operation since 1914.Nichols Hardware - A Purcellville Virginia landmark.

Read an article on Nichols' 100 year anniversary.

Nichols Hardware - A Purcellville Virginia landmark

Nichols Hardware in Purcellville is a trip back in time. With its uneven wooden floors, tin ceilings and overflowing shelves, this western Loudoun County icon embodies a period of American history when personal service and word-of-mouth advertising were the keys to retail success.

In many ways, Nichols doesn't look much different from the store that was founded in 1914. To the casual eye, the store may resemble a flea market hodgepodge, similar items gathered together, but with no real rhyme or reason. Every bit of space is used-even the ceiling from which dangles a tricycle and canoe on sturdy chains. Nichols Hardware opened its doors as the E.E. Nichols & Company in 1914. After the death of Ed Nichols and his son Ted Nichols, the store is now run by Ed's brother Ken Nichols.

Click image to enlarge. Nicholes Hardware carries almost everything you need. A panoramic view of the store

The Store's History

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

A few days before Christmas 1914, Edward Enoch Nichols and Paul Ambrose Warner opened Nichols Hardware in downtown Purcellville. Today, Nichols is the oldest retail store in the Virginia Piedmont still owned by its founding family.

Christmas 1914 was a time of sadness and rebuilding in the town of 500. Two late-November fires had destroyed seven frame stores and the board sidewalks on both sides of Main Street. Intense heat blew out the front windows of the nearly complete Nichols Hardware building. But the building itself was made of brick as a protection against fires, which were then endemic in small-town Virginia.

Nichols's son Ed Nichols Jr., who succeeded his father as store owner, told me several years ago how the family got into the hardware business.

"He wanted to be a lawyer," Nichols said of his father. But his grandfather, Jesse Nichols, who farmed south of Purcellville, had declared that "one lawyer in the family is enough." The lawyer was Jesse's brother, another Edward Nichols, of Leesburg.

Edward Enoch Nichols majored in industrial arts at George School in Bucks County, Pa., in the early 1900s. The school had long been the preparatory school of choice for bright county Quakers.

"My father was so good," Nichols Jr. told me, "that he ended up assisting the teachers."

Nichols Sr. then taught industrial arts in Kansas City, Mo., in a job he'd heard about through his older sister, Mabel Lybolt, an English teacher in Kansas City. She would later teach at Lincoln High School and become editor of Purcellville's Blue Ridge Herald newspaper.

In Kansas City, Nichols met Sarah Leach, a fifth-grade teacher. They married and returned to Nichols's hometown in 1913, hoping to buy a hardware store owned by cousin Joseph Vandeventer Nichols.

But J.V. Nichols got a better deal from M.H. Beall and sold the store to him. As compensation, J.V. Nichols sold his cousin a plot of land around the corner on 21st Street, and Ed Nichols Sr., with financial help from Warner, began a hardware partnership.

Their newspaper ads read: "Call Central, and Say 'Nichols & Warner, Please.' That's Us. We have the largest and most compete stock of hardware and furniture in the county. Prices Right."

Nichols soon decided he needed another way to make money, so he started a picture framing business in the store's basement and taught classes in framing and woodworking.

In finer homes from the 1880s through the 1920s, framed pictures and photographs were usually hung from machine-carved wooden molding running below the ceiling. They were suspended on wires attached to the molding with metal picture hooks shaped like question marks. Forty years ago, I found out that Nichols Hardware was the only store west of Washington that carried picture hooks.

The framing business and classes that were conducted into the 1920s evolved into other enterprises. Today, Nichols is one of the few hardware stores in the area that will screen frames and repair screening, sharpen knives and shears, repair lamps and electrical fixtures, and cut and thread steel pipes.

Beall sold out to Millner & Spear about 1920 and became a partner in the upscale Washington hardware store Fries, Beall & Sharp. Nichols Sr. became sole owner of his store in 1919 and then bought out Millner & Spear, "one of 11 hardware stores we would eventually buy out," Nichols Jr. said.

Nichols Sr.'s 14- to 15-hour days began shortly after 5 a.m. — when Purcellville's electricity came on — to accommodate dairy farmers who brought milk to the railroad station. At 6, the milk cans boarded the Washington & Old Dominion![]() train bound for Rosslyn.

train bound for Rosslyn.

The farmers sometimes stopped at Nichols, mainly to chat. Saturday was their buying day, and they would often take their families along, because Saturday night was movie night.

Asa M. Janney, who ran the Home Run Clothing Store, a door away from Nichols Hardware, was a regular nighttime helper in the early days. Janney had clerked in J.V. Nichols's hardware store and would come over to help unpack and stock merchandise. They could work until midnight, when the town's electricity was shut off.

As the store stocked more and more merchandise, the aisles became narrower. Janney's son, Asa Moore Janney, recalled that his father told Nichols Sr., "Don't worry; if they fall over it they might buy it."

Asa Moore Janney said that both Nicholses, father and son, believed in the merchandising concept of "Lovely to look at, delightful to hold; if you should break it, consider it sold."

The store was enlarged in 1920, and a furniture wing was added. Lester Cummings's livery stable next door was purchased in 1923. The livery was just about out of business as automobiles were fast replacing horses and buggies.

Nichols needed the stable for storage, and it was a relief to both him and neighbor William S. Steele, who ran a Ford dealership, that Nichols bought the large frame building: Cummings and his friends had smoked incessantly while carrying on a day-and-night card game next to the hayloft.

J. Terry Hirst, a Purcellville councilman and founder of Leesburg's J.T. Hirst hardware in 1927, told me some years back that Steele kept saying, "Blom [gosh], Eddie, that building is going to burn down and burn us both out."

The 1915 stable, still used for storage, remains Piedmont Virginia's outstanding building of that type and style.

Among the goods originally stored in the stable were cast-iron Majestic wood-burning cook stoves, shipped by rail from St. Louis. The four-lid stoves, heavy as "two men and a boy," Nichols told me, cost more than $100 and were bestsellers among the big-ticket items. In winter they could heat a small house.

In Nichols Hardware's first two decades, $100 was equivalent to about three months' income, and nearly every customer paid a bit down each month. The store did not charge interest until the mid-1970s. Before that, "about a quarter of our business was cash sales," said Nichols Jr.

The single most expensive item sold was a $500 top-of-the-line 78 rpm Victor gramophone in a console made of Circassian walnut. It was bought by Nichols Sr.'s uncle, lawyer Edward Nichols, and is owned today by Nichols Jr. The smaller, more common Edison cylinder machines sold for $30.

Nichols Jr. recalled that about 1922, his father and the Victor Talking Machine Co. rented the Bush Meeting Tabernacle (now used for Purcellville Baptist Church services) to demonstrate its gramophones.

Victor brought a soprano. The lights were turned out, and audience members had to guess whether they were hearing her voice or the gramophone.

Stag brand paints were another standard item of the day. At the eastern approach to Purcellville was a stick sign that read, "Use Stag Paint, one gallon makes two." Nichols Jr. recalled that the paint was concentrated and could be mixed with a gallon of linseed oil, which cost less than the $1 gallon of paint.

Purcellville had been electrified in 1912, but most farms and rural homes did not have electric power when radios became popular in the late 1920s. A heavy, elongated battery, about the size of an auto battery, was needed to operate them. Nichols Jr. said they sold for $5 and lasted about 1,000 hours.

Tri-County Electric Cooperative's lines began stretching across the western Loudoun countryside in the late 1930s, rendering the radio batteries obsolete.

About the same time, Nichols started selling a six-cubic-foot Kelvinator refrigerator for $99 -- $10 down, $5 a month. Nichols didn't have to worry about bookkeeping, because Tri-County added the $5 payment to customers' monthly electric bill and then paid the $5 to Nichols.

Tractors did not come en masse to the Virginia Piedmont until the late 1940s, when manufacturers converted from war materials to farm machinery. From its beginning, Nichols had sold hames, harnesses, horseshoes and horse collars, and about 1948, Nichols Sr. found himself saddled with 200 horse collars.

Finally he found a buyer in Intercourse, Pa., in the heart of Amish country. The Amish faith prohibited the use of mechanized equipment. Nichols Sr. chauffeured the buyer to Purcellville and back, and he purchased the bulk of the lot for $2 a collar.

Nichols's billing department entered the modern age in 1949, when it retired the last of its ledgers noting item purchased, customer, address and payment due. The customer began to receive a carbon receipt.

Yvonne Singhas Lickey came to Nichols to keep the books when the new system started. She officially retired in 1994 but still works part time, overseeing the keeping of handwritten records. Her sister-in-law, Glenda Rickard Lickey, had the same job from 1956 to 1992.

Customers still receive that handwritten receipt. There are no computers in Nichols Hardware. As Nichols has told me more than once, "You don't fix what's not broke."

Knowledge of yesteryear's hardware and the dispensing of free advice have been among Nichols's hallmarks. Nichols Jr., brother Kenneth Nichols and Hugh Edmonds have been behind the counter since the late 1940s. Nichols Jr. said recently that the average tenure of Nichols's clerks is "at least 20 years."

Copyright © Eugene Scheel