Loudoun County Burning Raid

Article One:

Grant orders Union General Sheridan to retaliate against Mosby's raids

By the Virginia Civil War Centennial Commission, County of Loudoun, Commonwealth of Virginia. Text by John Divine, Wilber C. Hall, Marshall Andrews, and Penelope M. Osburn. Edited by Fitzhugh Turner. Published by the Virginia Civil War Centennial Commission 1961-1965.

In late December, 1862, Major General J. E. B. Stuart came into Loudoun County from his position at Dumfries and Burke's Station, and established his headquarters near Dover (on what is now Route 50 between Aldie and Middleburg). On the morning of his departure, he granted permission to one of his trusted scouts to remain behind and operate against the enemy "for a few days."

Little did Stuart know that by granting this permission he was launching the career of one of the most successful of all "partisan rangers", for this scout was John S. Mosby, and the "few days" extended over a period of more than two years. Mosby established his seat of operations in northern Fauquier County and southern Loudoun, and from points within this area he ranged far and wide to harass Union wagon trains, scouting parties, and loosely-guarded outposts and garrisons.

" Mosby's Confederacy" embraced that area from Snickersville along the Blue Ridge into Fauquier County (Rt 601), to Linden; thence on a line running through Salem (now Marshall), and The Plains to the Bull Run Mountains; then along that range to Aldie; thence along the Snickersville turnpike (Rt 632) to the place of beginning at Snickersville. The confines of this area were by no means the limits of his operations, for the Federals within a radius of fifty miles were never safe from his attacks.

When Sheridan launched his Shenandoah Valley Campaign in the summer of 1864, Mosby immediately became the nemesis of his supply lines. On August 16, Grant sent the following instructions to Sheridan. "If you can possibly spare a division of cavalry, send them into Loudoun County to destroy and carry off the crops, animals, negroes, and all men under fifty years of age capable of bearing arms . . . In this way you will get many of Mosby's men."

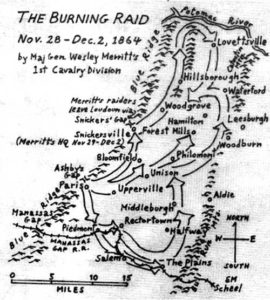

Sheridan, busy with his operations against Early in the Valley, did not have time to comply with Grant's instructions until November 27, 1864. On that date he issued an order to Major General Wesley Merritt and his 1st Cavalry Division, which was to have its effect on Loudoun County for many years:

" ...You are directed to proceed tomorrow morning with the two brigades now in camp to the east side of the Blue Ridge, via Ashby's Gap, and operate against the guerillas in the district of country bounded on the south by the line of the Manassas Gap Railroad as far east as White Plains, on the east by the Bull Run Range, on the west by the Shenandoah River, and on the north by the Potomac.

This section has been the hotbed of lawless bands, who have, from time to time depredated upon small parties on the line of army communications, on safeguards left at houses, and on all small parties of our troops . . .. You will consume and destroy all forage and subsistence, burn all barns and mills, and their contents, and drive off all stock in the region the boundaries of which are above described.

This order must be literally executed, bearing in mind, however, that no dwellings are to be burned and that no personal violence be offered to the citizens . . .. The Reserve Brigade of your division will move to Snickersville on the 29th. You will return to your present camp, via Snicker's Gap, on the fifth day."

This order was to unleash war at its worst, for the next five days were to see great destruction of property and loss of livestock. On November 28, General Merritt with the 1st and 2nd Brigades came through Ashby's Gap. Two regiments of the 2nd Brigade turned north from the base of the Blue Ridge to Bloomfield. Two regiments of the 1st Brigade went into Fauquier County. All met and camped at Upperville that night.

The next day the 1st Brigade went into Fauquier County, through Rectortown, Salem (now Marshall), and White Plains, returning to Middleburg. There they joined the 2nd Brigade, and swept the country between Millville and Unison-Bloomfield to Philomont, where they camped. The Resent Brigade came from its camp in Frederick County to Snickersville. On the 30th, the 2nd Brigade went north through Hamilton, Water- ford, and along the banks of Catoctin Creek to the Potomac River, then turned toward Lovettsville.

In the meantime, the Reserve Brigade went through Woodgrove, Hillsboro, and down the west side of the Short Hill Mountains to the Potomac; it then turned toward Lovettsville to meet, and camp with the 2nd Brigade.

December 1st saw the 2nd Brigade and the Reserve Brigade marching south toward Purcellville and then west to Snickersville, driving their captured herds with them. The 1st Brigade was still operating in the south end of the County; Middleburg, Millville, and Philomont. From there they moved to Snickersville to join the other two brigades. On December 2 the entire division left the County through Snicker's Gap .Loudoun County, Virginia

General Merritt's preliminary report, made on December 3, was not detailed; only conservative estimates were made. This report stated that Sheridan's orders were "literally" complied with, and "from 5000-6000 head of cattle, 3000-4000 head of sheep, and 500-700 horses had been driven off, while 1000 head of fatted hogs had been slaughtered." The Reserve Brigade was the only one to give a detailed report of their operations. This lists as burned 230 barns, 8 mills, 1 distillery, 10,000 tons of hay, and 25,000 bushels of grain.

While never officially reported, the damage to Loudoun was over a million dollars, and for many years after Appomattox the effect of these five fateful days were severely felt. Even in 1960 a few grim reminders are still evident in the form of blackened stone walls, once the foundations of sturdy barns or mills, in the area of what is now Purcellville and Round Hill.

Article Two:

Burning Raid Left Loudoun Barns and Mills

in Ashes

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

Several thousand Union soldiers raided western Loudoun County and northern Fauquier County from Nov. 28 to Dec. 2, 1864, in what has been called "The Burning Raid." The destruction they wrought upon the civilian populace and farms was, for both counties, unmatched during the Civil War. Ruins of burned buildings remain today, including Potts's mill near Hillsboro and Roach's and Grubbs's mills near Taylorstown.

Ulysses S. Grant, general in chief of the U.S. armies, stated the purpose of the raid in a communique to Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan on Aug. 16, 1864, 10 days after Grant had given Sheridan, 33, command of Union armies in the Shenandoah Valley:

"If you can possibly spare a division [about 6,000 men] of cavalry, send them through Loudoun County to destroy and carry off the crops, animals, negroes, and all men under fifty years of age bearing arms. In this way you will get many of Mosby's men. All male prisoners under fifty can fairly be held as prisoners of war, not as citizen prisoners. If not already soldiers, they will be made so the moment the rebel army gets hold of them."

John Singleton Mosby and his several hundred partisan rangers had been living off the land in southwestern Loudoun and northern Fauquier for a year and a half, after having commandeered crops and stock in what was considered the finest farmland in Virginia.

Increasingly, Mosby had been successful in random hit-and-run skirmishes and raids against Union forces. In July 1864, at Mount Zion Church![]() (a mile east of Gilbert's Corner and now owned by Loudoun County), he had routed a superior command, killing, wounding or capturing 105 of 150 cavalrymen.

(a mile east of Gilbert's Corner and now owned by Loudoun County), he had routed a superior command, killing, wounding or capturing 105 of 150 cavalrymen.

Sheridan could not spare the cavalry division to go after Mosby until he ended Confederate resistance in the Shenandoah Valley. That opposition effectively ceased with a Union victory at Cedar Creek, south of Winchester, on Oct. 19. Sheridan withdrew southward, ravaging the valley from Harrisonburg south to Staunton.

"It was a hard war then, with both armies taking it out on civilians," Civil War historian Taylor M. Chamberlin said recently.

Chamberlin's great-great-grandfather Edward Young Matthews had his Waterford area barn burned and cattle taken during the Burning Raid. His great-grandfather Capt. Simon Elliott Chamberlin was one of the raiders, though he did not burn Matthews's barn.

Chamberlin's 2003 book Where Did They Stand? details events leading to the raid, foremost among them, Grant's orders. Grant informed Sheridan that many Loudoun farmers were Quakers, "all favorably disposed to the Union." He emphasized that "in cleaning out the arms-bearing community of Loudoun County . . . exercise your own judgment as to who should be exempt from arrest, and as to who should receive pay for their stock, grain, &c."

Grant's final communique to Sheridan, on Nov. 9, asked whether it wouldn't be advisable "to notify all citizens living east of the Blue Ridge to move out north of the Potomac all their stock, grain, and provisions of every description" so the country couldn't "support Mosby's gang."

"As long as the war lasts they must be prevented from raising another crop," Grant said.

Sheridan's reply two days later did not answer Grant's question. He said one of his cavalry divisions had invaded Fauquier County via Manassas Gap and had burned crops and granaries and returned to the Front Royal area with 300 head of cattle and numerous sheep and horses.

Sheridan apparently wanted to wait and see who won the 1864 presidential election before carrying out this devastating action amid much anti-war sentiment. After Abraham Lincoln's overwhelming victory over George Brinton McClellan, who wanted to sign an armistice with the Confederacy, Sheridan sent a dispatch Nov. 26 to Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, Grant's chief of staff.

"I will soon commence work on Mosby," he said. "Heretofore I have made no attempt to break him up, as I would have employed ten men to his one. . . . I will soon commence in Loudoun County, and let them know there is a God in Israel."

On Nov. 28, Sheridan sent Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt's cavalry division through Ashby's Gap to begin a week of destruction in Fauquier and Loudoun. Merritt's troops scoured the valley between the Blue Ridge on the west and the Bull Run and Catoctin mountains on the east, and from the Manassas Gap Railroad on the south to the Potomac River.

"This section has been a hot-bed of lawless bands, who from time to time have depredated upon small parties," began Sheridan's order to Merritt and his officers, and in Chamberlin's Where Did They Stand? he quotes the order, a copy of which was given to his great-grandfather and is now a family heirloom.

"You will destroy and consume all forage and subsistence, burn all barns and mills with their contents, and drive off all stock in the region the boundaries of which are described above . . . no dwellings are to be burned and that no personal violence be offered to citizens."

In my book The Civil War in Fauquier, I wrote that several of Mosby's rangers were having dinner the evening of Nov. 28 at Ayrshire, a manor house north of Upperville, when one of them, James Williamson, said he "saw flames bursting out in the direction of town, from burning hay-stacks, barns, and stables."

At nearby Greengarden, the Joshua Fletcher place, the soldiers destroyed the winter's supply of pork by roasting live hogs on a burning pile of fencing rails.

South of Upperville at Oakley, where two serious battles had taken place earlier in the war, Ida Powell Dulany wrote in her diary that on the evening of Nov. 28, Union officers warned her that her outbuildings and crops would be burned. When she asked them why, they replied, "To render it [Oakley] utterly uninhabitable for Mosby's Guerrillas."

Dulany had time to have her servants herd the plantation's cattle to a nearby woods. In her diary, she noted that early the next morning, she awoke to see "about thirty soldiers . . . to the haystacks and soon had them blazing. . . . Two Yankees stayed by the granary till the flames made such progress that it was impossible to save it." She saw "the barn starting to burn, and the flames were bursting out of the large stable door."

When the soldiers left, her children, slave children and servant "Uncle Josh" began a bucket brigade to put out the barn fire, but the haystacks and granary "were burned to the ground."

Her diary entry a few days later stated that from Oakley's heights "we could mark the progress of the Yankees, in every direction dense columns of smoke arising one after another, from every farm through which they passed. . . . At night we could look out and see the whole country illuminated by immense fires."

Mary Cochran, a Middleburg resident, wrote in her diary Nov. 28 that Union troops entered town and that a "full band Struck up & sent forth its lively strains & at the same moment half a dozen fires burst forth at different points . . . was soon ascertained that the burning was confined to barns & stables & God who so mercifully tempers the wind kept it from spreading the flames."

"The streets were soon filled with women rushing after their cows . . . all the oxen were taken -- how were the people to be supplied with wood . . . the tramp of this Ruffian Soldiery on their devilish errand can never be forgotten."

Lydia Janney, who lived at Forest Mills, south of Lincoln, wrote in her diary Nov. 30 that "soldiers rode up to the barn, but they found it would endanger the house so they left the barn, going to the mill. I pleaded with them, telling them father [Asa M. Janney] was an old man, had no sons to help him make a living, but the man I was talking to said: 'Casey, is everything ready? Strike a match.' And the mill was on fire."

Lydia Janney's sweetheart, Will Brown, rode through the farmland south of Lincoln that day and told her he had counted 150 fires, including the one that burned his family's barn at Montrose.

Janney and Brown were among many hundreds of pro-Union Quaker families whose crops and buildings were destroyed that week. As most Quaker men were pacifists, and avoided conscription into either army, their farms were often the most prosperous and thus suffered the most damage.

Some Union commanders were sympathetic to the Quaker farmers and mill owners. Chamberlin cites the reminiscence of a Union captain in the command of Brig. Gen. Thomas C. Devin. Devin knocked on the door of David Mansfield, a Quaker miller who had previously entertained the general, and told Mansfield he had better have some buckets of water ready should his house catch fire.

His adjutant then placed dry wood against Mansfield's nearby mill and ignited it. The adjutant and Devin quickly rode away. Mansfield put out the flames with the water, with the reminiscing captain noting: "Thus Gen. Devin was made happy, and a loyal man fully repaid for his generous hospitality."

Ruses saved some buildings and crops.

Thomas Hawkins Clagett, a physician who lived at Woodburn, southwest of Leesburg, sent slaves and farm help to meet the Union soldiers before they approached the plantation. Clagett's servants told the soldiers that Mosby's men were awaiting them in ambush.

As the would-be burners had previously received Union reports that Mosby was in the area, they avoided Woodburn. The circa-1820 brick barn and 1777 stone mill, one of the area's oldest, stand today.

Northwest of Philomont, John James Dillon pretended to welcome the Union burners the chilly evening of Nov. 30 and suggested they join him and sample homemade hard cider. Dillon also recommended that they sleep in the windowless barn so they would be safe in case they were fired upon. Dillon and the raiders then stayed up all night chatting, and in the morning the Union troopers just rode away. The barn still stands.

Sheridan estimated that 6,000 cattle, 5,000 sheep, 1,000 fatted hogs and 700 horses were seized or killed during the Burning Raid. Only one of Merritt's three brigades -- a brigade usually numbered 2,000 men -- cited damages to buildings and crops: eight mills, 230 barns and one distillery burned, and 10,000 tons of hay and 25,000 bushels of grain burned or were carried off.

Most newspapers reporting the raid decried the destruction and said it did not achieve its purpose to drive out Mosby's men.

The Alexandria State Journal, Virginia's only pro-Union newspaper, editorialized that even though "Union people" bore the brunt of the destruction, it would take more than having "some of these poor creatures [stock] burned before their eyes . . . even more than that to make them rebels."

Chamberlin lists the claims and money received of the 240 people who applied to federal authorities for compensation in 1865. Only those who proved their loyalty to the Union could receive reparations, and only in January 1873 did the funds arrive, minus 10 percent to government lawyers.

Chamberlin's great-great-grandfather died in 1867, having been psychologically and physically drained by the loss. His estate received $3,708. His barn was rebuilt but was blown down in this year's windstorms.

Matthews did, however, win a son-in-law in the exchange. At Lovettsville, where Matthews filed for remuneration, the claims officer was former raider Simon Elliott Chamberlin. He fell in love with Matthews's daughter Edith, and they married two years later. The couple lived at Clifton, Matthews's farm, which remains in the family.

Will Brown's family received $3,397 for their two burned barns, and Asa M. Janney $6,782 for his burned Forest Mills. The barns stand today. At age 72, Janney did not rebuild the mill. His daughter Lydia married Brown in May 1866. Most of their farm, Circleville, remains in the family today.

Copyright © Eugene Scheel