Goose Creek Canal – An Ill-fated Project

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

More on Loundoun's early transportation »

People are now able to walk along the ill-fated Goose Creek Canal for the first time and learn the history of its remarkable double-stone locks. The locks are in one of Loudoun County's newest historical preserves, the Elizabeth Mills Riverfront Park, which borders the Potomac River and "The Goose."

The canal and its many associated stone ruins, primarily the deserted village of Elizabeth Mills, the park's namesake, are mementos of an era when inland waterways were thought to be the last word in commerce.

The Goose Creek and Little River Navigation Co., the canal's official name, had its beginnings in 1830, when investors met at the old Peers Hotel (later the Laurel Brigade) in Leesburg to discuss the idea. They needed to raise about $40,000, with the state funding the remaining 60 percent, Virginia's norm for all private-public transportation partnerships of that era. It took nine years to raise the private money, partly because of a mid-1830s depression and uneasiness about railroads, which threatened to replace canals as the major transportation link between Loudoun and East Coast seaports.

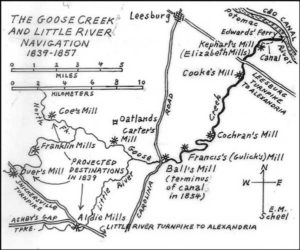

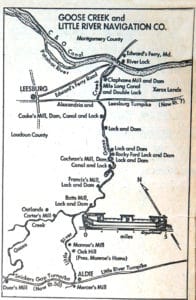

The aim was to render Goose Creek navigable from the Potomac River to three large water-powered mills about 20 miles away. Grain that was ground at these and six other large mills along the creek could be taken by boat across the Potomac and, via a lock, to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal near Edwards Ferry. In eight hours, the produce would arrive in Washington or Alexandria, where goods for overseas export commanded high prices. Horse-drawn road travel to the ports took twice as long, because horses had to be rested overnight.

Engineers Gen. William Gibbs McNeill – a West Point man and surveyor of the C&O, James River and Kanawha canals – and John Henry Alexander, the topographical engineer of Maryland, surveyed Goose Creek and planned its canal works in the late 1840s. After discussions over the merits of wooden or stone locks, the more expensive stone was picked for durability. The length of the locks, however, was halved from a proposed 104 feet, the length of locks on the C&O Canal.

Construction began in December 1849. The 10-year delay was due, in part, to growing doubts about canal travel vs. speedier rail – proposed in Loudoun but not yet built – and the death of the canal company's first president and prime investor, George Carter of Oatlands.

By the close of 1850, the rare double locks (called outlet locks) a quarter-mile from the Potomac had been completed. The Seneca sandstone was transported from nearby quarries. Ground grain from George Kephart's Elizabeth Mills, a half-mile upstream from the outlet locks, could now be floated to the C&O Canal, a little more than a mile away. The canal boats were poled through the water; no mules guided the craft in the bypass canals.

The mill, and its adjoining village of stone and brick, took its name from Elizabeth Clapham, who, with her father, Samuel Clapham, owned the mill from 1807 to 1828. The mill was operated until sometime during the Civil War, when it was burned by Union soldiers. The trail through the new park links this village with the double outlet locks and the Potomac River. Park planners hope eventually to extend the trail south to the other mill and canal-lock ruins of Goose Creek.

By the close of 1851, the navigation was open for seven miles. That year's director's report to the state and stockholders noted that the four completed canals, locks and dams were "not surpassed by any improvement in the state." But "in order to give that degree of strength and solidity to the locks and dams," the system had to be truncated so that it ended at Ball's Mill (today's Evergreen Mills) -- 12 miles from the Potomac instead of the hoped-for 20.

In 1854, the last lock and dam were completed at Ball's Mill. It had been a dry spring and early summer, and sandbars were building up on the hitherto navigable stretches of Goose Creek. The canal company's president, Humphrey Brooke Powell of Middleburg, wouldn't pay the contractor until a canal boat was able to navigate the entire works. So Powell had a boat built at Cumberland, Md. -- 11 feet by 42 feet, with a 31-ton capacity -- to test the improvement.

Paul Carter, a miller at Evergreen Mills, told a story about the boat's voyage. I heard it on a tape-recording many years ago. Slaves dragged the boat across the sandbars and through shallow water to Ball's Mill. The contractor and crew were paid. In low water, one can still see the craft's remains in the old mill pond.

Powell's annual report that year did not mention the only known boat to navigate the entire works. He told of the canal's "languishing condition, from which there is little hope that it will recover." He blamed the railroads, "which drew off many of [the canal's] early friends and advocates."

Powell's final report to the state and stockholders, written in the midst of the depression of 1857, again picked on railroads as the main cause for the canal's failure. One railroad was under construction in Loudoun, and construction was shortly to begin on the other. Powell closed his letter with these words about the Goose Creek Navigation: " . . . candor compels me to say that I consider it of little value either to the state or to the individuals who have expended their money on it." The company's books showed a balance of $1.95.

For further reading: For a full story of the canal, including maps and diagrams, see William E. Trout III's "The Goose Creek Scenic River Atlas" (Virginia Canals and Navigation Society, 1990). For histories of the various villages along the canal and Goose Creek, see Eugene M. Scheel's "Loudoun Discovered," Vols. 2-3 (Thomas Balch Library, 2002).

For related articles on canals related to Loudoun and Fauquier counties, see the July 6, 2003 (C&O Canal), and Jan. 20, 2005 (Rappahannock Canal), issues of the Loudoun Extra.

Copyright © Eugene Scheel